The Possibility of Alienation

Exhibition Essay by Sumesh Sharma – co-curator, Clark House Initiative, Mumbai

The possibility of alienation in a city that claims cosmopolitanism as a constant, cannot be attributed to the loss of cultural space specifically due to revisits to the city’s history, but bizarrely it has and specifically in particular name change that occurred many years go now erases those many diverse histories. Ali Akbar Mehta studied at the JJ School of Art that stood at the beginning of the road that leads into the city’s eastern districts. As one drives onto a flyover that shares the same name with Ali’s school and was built to circumvent the congestion and surely the people who gather at Bombay’s famous Bhendi Bazaar, one witnesses many ‘Stars of David’ that adorn the muralesque facades of the neo-gothic and art deco buildings that exist on the stretch. Here ‘Mumbaikars’ stare into the homes from the cars of a community whom they might not easily find in the endogamous housing societies of Bombay.

The buildings that line the roads of Bhendi Bazaar were built by Jewish merchants who were Sephardic immigrants from Baghdad and were initially inhabited by indigenous Bene Israelis from the Konkan hinterland, soon Muslim tenants replaced the migrating Baghdadis and the area soon was host to many different merchant communities which include the Dawoodi Bohras, Jains, Ismaili Khojas and Memons. In the days of a siege that slaughters thousands in Palestine, Jewish charity runs a school mostly attended by Muslim children while the synagogue is colloquially called the mosque. Not far from here is Mazgaon that translates from Marathi as ‘My village’. The varied urbanscape today actually arose from leafy plantation houses that once house the East Indians of Bombay and Parsis who were escaping the malarial crowd of the city. The East Indians were descended mainly from indigenous fishing communities that were converted to Catholicism by the missionaries’ activities of Portuguese missionaries and inquisitions against the locale populace. A certain bourgeoise arose from families that claimed Mulatto or Portuguese descent, one such family was the De Souza – De Lima family that was granted Mazgaon as an agricultural estate. The Island of Bombay contained many East Indian villages and Matharpakadi is one that remains though constantly nudged by realtors essentially a village.

Mazgaon was a geography of military intrigue and was fought over for by the Abyssinians sealords of the Mughals, Marathas and the Parsis. These wars changed the use of land in the area as it was distributed. The Parsis specifically the Wadia family began a ship building yards, the Bohri Muslims began to service the trade as grocers, petty exporters and in recent years the primary actors in the marine hardware and boat construction business. The Chinese dockworkers, dentists and tanners set up a China town with a Taoist temple and a cemetery not far away. The Chinatown was dismantled after the Indo-China war along with its Mahjong clubs and its residents packed of to internment camps in the arid heat of Rajasthan.

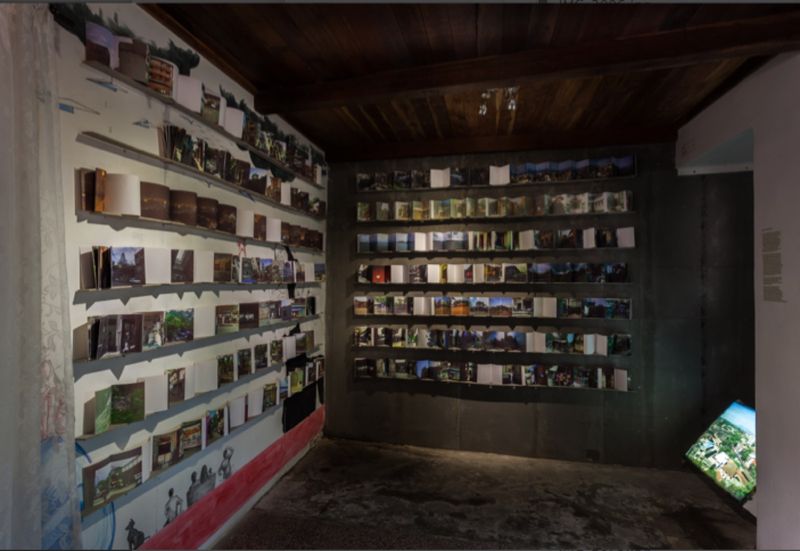

Ali Akbar Mehta maps Matharpacady, the remnants of Chinatown, his Bohri grandparent’s apartment and the Wadi Bunder where ships are brought to be torn apart on the dry dock. Here he fights nostalgia by documenting it, recreating it through videos, conversations and staging ethnographic reconstructions of people’s homes within Clark House. The structure of the art space, which is of an early 20th century colonial apartment, lends itself with ease to these interventions. Through these interventions Ali stages a dramatic critique on the ghettoisation of the city on communal lines into two communal flanks of east and west after riots of 1993. Alienation manifests in drawings of superheroes who stretch across the city’s skyline, these are drawn on gateway paper illuminated using the reflection of light and mirror. They are placed aside scenes of the Mazgaon recreated by a poster painter who refers through Ali’s photographs while rendering them using a palette of colour scene in the colonial Bombay School and often used to stage revisits to the city’s history by Bollywood. Site, Structure and Stage thus reclaims a space by revisiting certain histories purposefully ignored in writing the city’s history by creating narratives around architecture, language, mercantile culture and personal histories around a site that demarcates a certain geography.

– Sumesh Sharma