Odes and Inquisitions: Sino-Indian Connections in Recent Indian Art

Essay by Ryan Holmberg

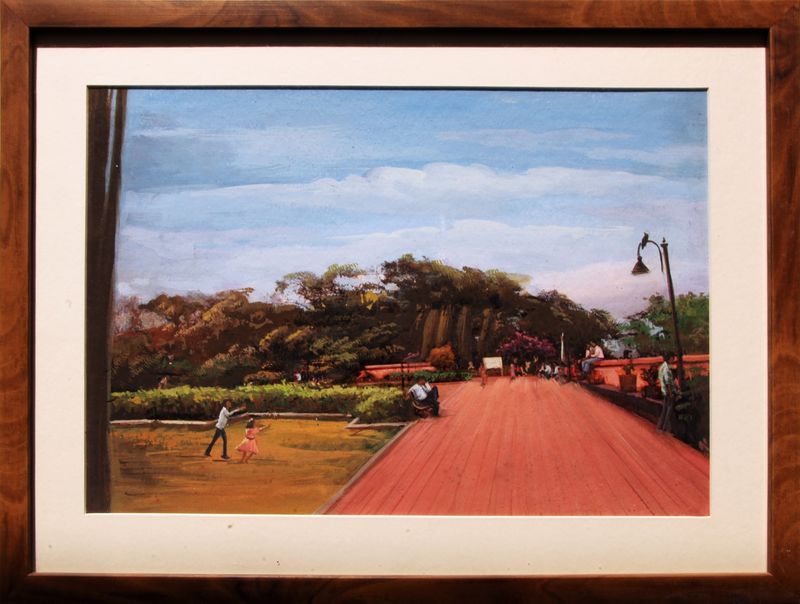

The Joseph Batista Gardens is one of the pleasantest places in Mumbai. Sitting atop a hillock, the garden park literally lifts you out of the noise from which even the surrounding neighborhood of Mazagaon, sedate by Mumbai standards, cannot escape.

To the north and west one gains a distinct view of the many mildew-stained high-rises that contribute to one of the highest population densities in the world. To the south, one sees rows upon rows of warehouses and train sheds. And to the east, a clear view of the city’s historical raison d’etre: Mumbai harbor, populated now with freight and naval ships, once open a time with frigates and opium clippers. It is not a picturesque view, for towering in the middle is a massive, yellow gantry crane inscribed with the words “Mazagaon Dock Limited, Shipbuilders to the Nation.” As advertised, this is India’s top shipyard, creating warships and submarines for the Indian Navy, offshore platforms for the oil industry, and tankers and cargo carriers for commercial shipping.

The site of Mumbai’s former Chinatown, centered on Nawab Tank Road, lies in the crane’s shadow. The dockside location reminds one that the basis of the overseas Chinese community in India, like in most places across Asia, was the centrality of China in international maritime trade in the early modern and colonial eras. Until the eighteenth century, Mazagaon was hardly more than a Portuguese fort surrounded by fishing villages. Both pleasantly verdant and conveniently adjacent to one of the best natural harbors in Bombay, the place was bound to change when Zoroastrian Parsi merchants and the East India Company made Bombay the new commercial center of Western India. By the mid nineteenth century, Mazagaon had become a fashionable suburb for Europeans and Parsi merchants, populated with many churches, private villas, and even a couple of luxury hotels. The shipyard dates back to the early nineteenth century. That is where the Chinese worked, reportedly mainly as nut and bolt fitters. What remains of that community, like the much larger one in Kolkata, is composed primarily of Cantonese, Hakka, and Hupei – which is to say, ethnic groups from the Pearl River Delta area and the main inland areas impacted by the opium trade that was developed by the Portuguese and the British in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

While Kolkata’s Chinatown holds on, Mumbai’s has been almost lost to oblivion. It registers so weakly in the city’s memory that even most lifelong Mumbaikars have never heard of it. Even at its height, Bombay’s Chinatown paled in comparison with that in Kolkata, which accounts for more than 90 percent of the country’s Chinese-Indian population. One has to dig for mention of Chinese residents in histories of colonial Bombay. When they do appear, they are merely one name in the colorful and multilingual crowd of traders and immigrants from across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East that made Bombay famous as the most cosmopolitan place in the Orient. “Chinese with pig-tails; Japanese in the latest European attire; Malays in English jackets and loose turbans; Bukharans in tall sheep skin caps and woollen gabardines,” closes Commissioner of Police S. M. Edwardes in his account of the ingredients of Bombay’s melting pot streets in the first decade of the twentieth century. Also in “certain clubs in the city where a man may purchase nightly oblivion for the modest sum of two or three annas” – which is to say, in the opium dens –“the proprietor of the club may be a Musalman; his patrons may be Hindus, Christians or Chinese.” Intoxication, Edwardes observes, overcomes “distinctions of race, creed and sovereignty” – not unlike, say, money and commerce did in the street. But when the sun went down (or, if you were an addict, when the sun came up), Bombay’s various ethnic groups returned to homes in communities that were more often than not segregated from one another.

None of this I would have known or bothered to look into had it not been for Ali Akbar Mehta’s Site : Stage: Structure (2013-14), a show at the Clark House Initiative, a quasi-non-commercial space in south Mumbai. A converted antiques shop of odd dimensions, tucked away spaces, and personal odds and ends, the Clark House tends to make everything installed in its space look like a cabinet of curiosities. Mehta’s Site : Stage : Structure – an impressionistic and sentimental survey of the neighborhood through a mix of video documentary, photographs, and personal knickknacks – appeared to be that by design.

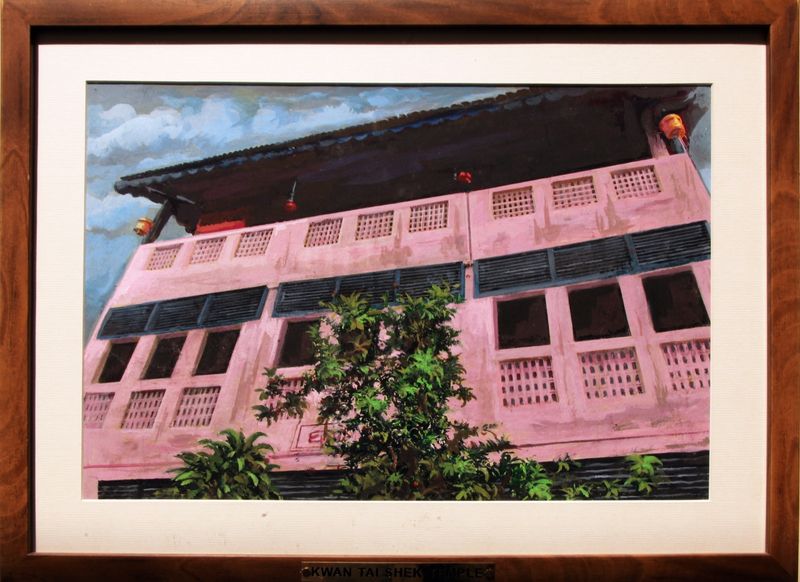

The focus of the installation was on the personal memories of the artist’s own grandparents and grandaunts and granduncles, all Bohra Muslims (another famed merchant community) who have been living in the neighborhood since the early twentieth century. They talk through video interviews about their daily lives, and about their family business of manufacturing fishing hooks, physical samples of which hang on the wall. There were also reflections of a less personal sort, and these were aimed at capturing the historical traces of Mazagaon’s slowly disappearing cosmopolitanism. Three fat photobooks focused on aspects of the neighborhood’s buildings and people. There were also photographs, taken by Mehta and hand-colored by a painter of movie hoardings hired by the artist, of the few surviving churches, crucifixes, and bungalows that once crowded this originally Portuguese settlement. In the same series was also an image of the giant crane at Mazagaon Dock, as well as one of the nondescript pink façade (beige in reality) of a three-story building that houses, on its second floor, the only distinctive remnant of the area’s Chinatown: the Daoist Kwan Tai Shek temple, dedicated to Guan Yu, the famous general of the Three Kingdoms period. It was reportedly built by Cantonese sailors in 1919. A Buddhist temple to the bodhisattva Guanyin was established on the building’s ground floor in recent years.

In another room at Clark House, Mehta had assembled images and objects related to the Kwan Tai Shek temple. On a shelf in the corner were a handful of ritual items, including cups and an incense burner, and figurines from Journey to the West. Pinned upon the wall behind them was a grid of sheets of silver-painted joss paper, burned to send wealth to deceased ancestors. A cabinet in another corner of the room contained various Chinese vessels. Some of the displayed objects were culled from the temple and its caretaker’s home. Others were fashioned by the artist in a makeshift manner (simple canisters splashed with red paint, for example) similar to that used at the temple itself to create facsimiles of items not available in Mumbai

The centerpiece of the installation was a twelve-minute video. It featured artfully shot details of things like the temple’s bright red ceiling, burning incense, and armored Daoist gods. Some information about the temple’s history and its rituals are given in the voiceover, provided by the temple’s jaunty caretaker in a comically round accent. “No way, not while I’m alive,” he says, responding to an unheard question of whether the temple will be dissolved and the land sold. Yet his defiance, and the fact that on most days the temple stays locked and unused, raises the specter that perhaps this generation of Chinese-Indians will be the last to stand up for tradition.

Granted, the Chinese settlement was only one part of Site : Stage : Structure. But as the installation overall could have benefited from a clearer mapping of the neighborhood’s shifting demographics, so the Kwan Tai Shek component might have foregrounded why Bombay’s Chinatown has been reduced to fragments. In 1962, during the Sino-Indian War, many Chinese-Indians, not unlike Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor, were either deported if they didn’t have Indian citizenship or sent to internment camps in Rajasthan and Gujarat if they did. Returning to their homes after the war ended, many found their property and businesses damaged or confiscated. In the spring of 1963, the PRC sent ships to India to repatriate those who wished to relocate to China. Others moved on their own to Western countries, many to Canada. The exodus continues to the present, with growing business opportunities throughout Asia, including China of course. Many of those who are educated abroad choose to stay on in those countries.

Though the internment camps and resulting outmigration are noted in a few scholarly texts, no historian has undertaken a full study. This episode was made known to a wider public a few years ago through Rafeeq Elias’s The Legend of Fat Mama (2012), a documentary for the BBC about Kolkata’s shrinking Chinatown. The story Elias tells of persecution, marginalization, and disappointed emigration applies also to Mumbai, judging from the extensive wall text at Mehta’s Clark House installation. “According to Tulun Chen, Mumbai-based chairman of the Maharashtra Chinese Association,” reports Mehta from one of his many interviews with the community, “there are just around 3,500 Chinese in Mumbai, down from an estimated 15,000 in the mid-1960s.” Those who remain are now third and fourth generation. If they have not disappeared into Indian society, they run hairdressers and Chinese restaurants, including some of the most famous in the city.

Sketch-like though it might be, Mehta’s project is the most focused attempt to document the history and fate of Chinese-Indians in Mumbai. Information about the community is otherwise available only in the form of spotty online travel and entertainment blogs. Some of the artists and curators associated with the Clark House conduct related forms of urban history and ethnographic research, though I have never seen anything at the gallery on the scale of Site : Stage : Structure. Such projects not only enrich Mumbai’s art scene by offering something other than aesthetic wall-hangings and floor pieces, or theory-laden group shows. They also contribute to the city’s self-knowledge as a place with a conflicted and tangled cosmopolitan past. In an era in which rightwing groups continue to insist on Mumbai narrowly as a Hindu Marathi city, counter-historical practices like Site : Stage : Structure serve much more than ethnographic curiosity.

– Ryan Holmberg

*

Ryan Holmberg is an art and comics historian. After receiving his PhD in Japanese Art History from Yale University in 2007, he taught at the University of Chicago, City University of New York, and the University of Southern California. He is a frequent contributor to Art in America, Artforum, Yishu, and The Comics Journal, and is editor of two lines of translated manga from PictureBox, Inc. in New York: Ten Cent Manga, which focuses on the impact of American comics and mass entertainment on Japanese manga, and Masters of Alternative Manga. As a Sainsbury Fellow, Ryan is undertaking research that would eventually lead to the publication of his book project Garo and the Birth of Alternative Manga.

Ryan happened to walk in one fine day into Clark House, when he was researching a piece on Sino-Indian Connections in Recent Indian Art, which was published in the January/February 2015 volume of YISHU.