SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE

- SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE

- SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE

- The Possibility of Alienation

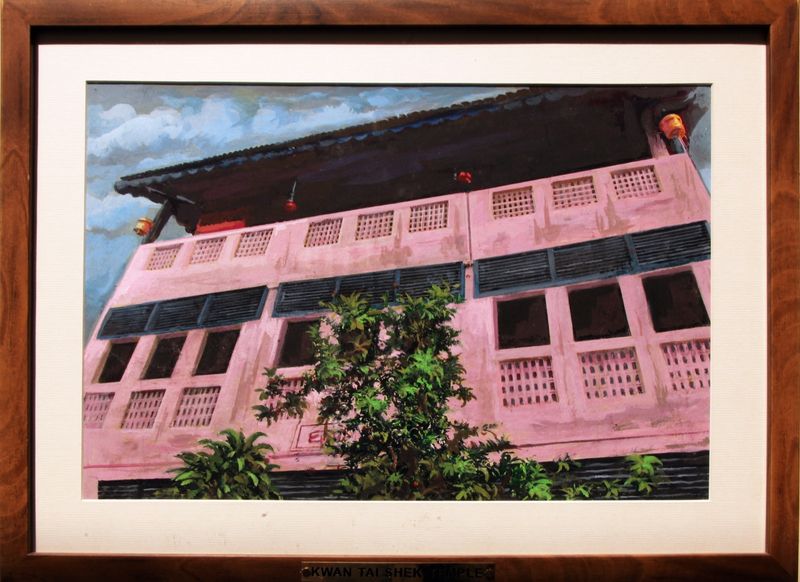

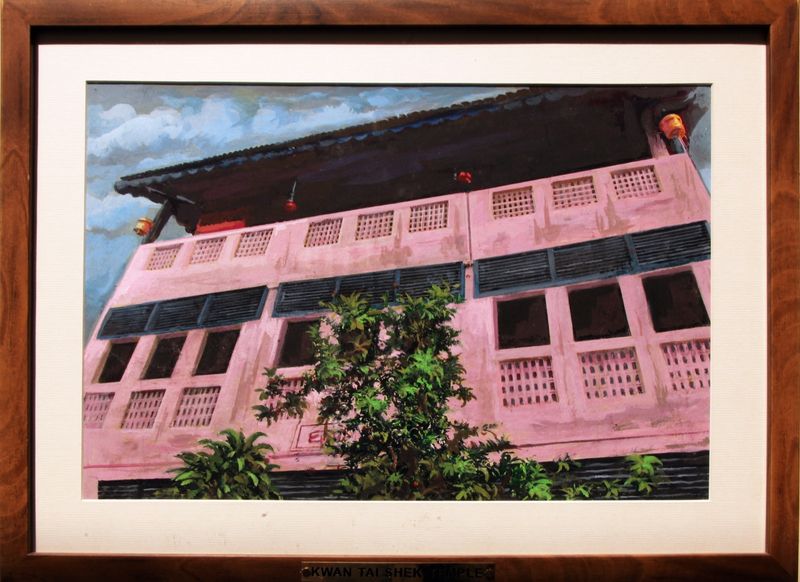

- Kwan Tai Shek Temple

- Mazgaon Interviews – Fakhruddin and Khateeja Merchant

- Mathar Pacady Interviews – Aunty Lavina and Uncle Martin

- Mathar Pacady Interviews – Mr. Julius Valladares

- Mathar Pacady Interviews – Aunty Tessi

- Paintings

- Making Space

- FOLKARCHIVE: Ali Akbar Mehta

- Memory and the Maximum City

- Odes and Inquisitions: Sino-Indian Connections in Recent Indian Art

- Chinese Fortunes and other Mumbai Memories

- Interview

- The BB Art Showcase: Ali Akbar Mehta

- The Possibility Of Alienation – Ali Akbar Mehta

- Site Specific

- Hidden Histories of Mazgoan

- A select History of Mumbai

- The Chinese in Mumbai

- The Origin of Kwan Yin or Miao Shan

- Shrikrishna Report

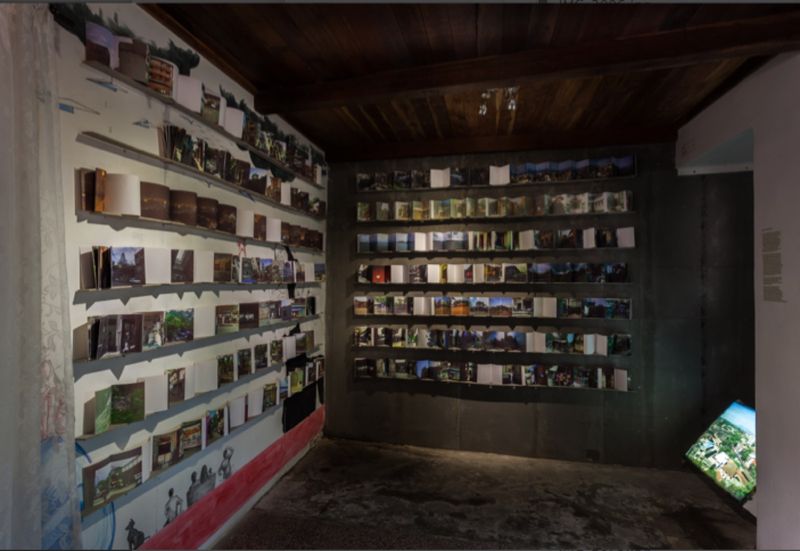

SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE is an archival documentary project. It is a Transmedia Installation that integrates books, objects, photographs, short films, audio narratives, and heritage walks as a way of revitalizing memories and telling a history that is absent from the formal narratives.

Site [sahyt] noun

- The position or location of a town, building, etc., especially as to its environment: the site of our summer cabin.

- The area or exact plot of ground on which anything is, has been, or is to be located: the site of ancient Troy.

Stage [steyj] noun

- Theater

- the platform on which the actors perform in a theater.

- this platform with all the parts of the theater and all the apparatus back of the proscenium.

Struc·ture [struhk-cher] noun

- Mode of building, construction, or organization; arrangement of parts, elements, or constituents: a pyramidal structure.

- Something built or constructed, as a building, bridge, or dam.

- A complex system considered from the point of view of the whole rather than of any single part: the structure of modern science.

- Anything composed of parts arranged together in some way; an organization.

SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE

Clark House, Mumbai

The Possibility of Alienation

Exhibition Essay by Sumesh Sharma – co-curator, Clark House Initiative, Mumbai

The possibility of alienation in a city that claims cosmopolitanism as a constant, cannot be attributed to the loss of cultural space specifically due to revisits to the city’s history, but bizarrely it has and specifically in particular name change that occurred many years go now erases those many diverse histories. Ali Akbar Mehta studied at the JJ School of Art that stood at the beginning of the road that leads into the city’s eastern districts. As one drives onto a flyover that shares the same name with Ali’s school and was built to circumvent the congestion and surely the people who gather at Bombay’s famous Bhendi Bazaar, one witnesses many ‘Stars of David’ that adorn the muralesque facades of the neo-gothic and art deco buildings that exist on the stretch. Here ‘Mumbaikars’ stare into the homes from the cars of a community whom they might not easily find in the endogamous housing societies of Bombay.

The buildings that line the roads of Bhendi Bazaar were built by Jewish merchants who were Sephardic immigrants from Baghdad and were initially inhabited by indigenous Bene Israelis from the Konkan hinterland, soon Muslim tenants replaced the migrating Baghdadis and the area soon was host to many different merchant communities which include the Dawoodi Bohras, Jains, Ismaili Khojas and Memons. In the days of a siege that slaughters thousands in Palestine, Jewish charity runs a school mostly attended by Muslim children while the synagogue is colloquially called the mosque. Not far from here is Mazgaon that translates from Marathi as ‘My village’. The varied urbanscape today actually arose from leafy plantation houses that once house the East Indians of Bombay and Parsis who were escaping the malarial crowd of the city. The East Indians were descended mainly from indigenous fishing communities that were converted to Catholicism by the missionaries’ activities of Portuguese missionaries and inquisitions against the locale populace. A certain bourgeoise arose from families that claimed Mulatto or Portuguese descent, one such family was the De Souza – De Lima family that was granted Mazgaon as an agricultural estate. The Island of Bombay contained many East Indian villages and Matharpakadi is one that remains though constantly nudged by realtors essentially a village.

Mazgaon was a geography of military intrigue and was fought over for by the Abyssinians sealords of the Mughals, Marathas and the Parsis. These wars changed the use of land in the area as it was distributed. The Parsis specifically the Wadia family began a ship building yards, the Bohri Muslims began to service the trade as grocers, petty exporters and in recent years the primary actors in the marine hardware and boat construction business. The Chinese dockworkers, dentists and tanners set up a China town with a Taoist temple and a cemetery not far away. The Chinatown was dismantled after the Indo-China war along with its Mahjong clubs and its residents packed of to internment camps in the arid heat of Rajasthan.

Ali Akbar Mehta maps Matharpacady, the remnants of Chinatown, his Bohri grandparent’s apartment and the Wadi Bunder where ships are brought to be torn apart on the dry dock. Here he fights nostalgia by documenting it, recreating it through videos, conversations and staging ethnographic reconstructions of people’s homes within Clark House. The structure of the art space, which is of an early 20th century colonial apartment, lends itself with ease to these interventions. Through these interventions Ali stages a dramatic critique on the ghettoisation of the city on communal lines into two communal flanks of east and west after riots of 1993. Alienation manifests in drawings of superheroes who stretch across the city’s skyline, these are drawn on gateway paper illuminated using the reflection of light and mirror. They are placed aside scenes of the Mazgaon recreated by a poster painter who refers through Ali’s photographs while rendering them using a palette of colour scene in the colonial Bombay School and often used to stage revisits to the city’s history by Bollywood. Site, Structure and Stage thus reclaims a space by revisiting certain histories purposefully ignored in writing the city’s history by creating narratives around architecture, language, mercantile culture and personal histories around a site that demarcates a certain geography.

– Sumesh Sharma

Kwan Tai Shek Temple

The Chinese in Mumbai

The Chinese in Mumbai In the early 19th century, hundreds of Chinese labourers joined the East India Company, working as welders, fitters, carpenters and cooks at its operations in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and Bombay (now Mumbai). The Company hired mainly Cantonese from Hong Kong, who were brought by ship to India, while others crossed the border into India from Burma.

In 1820, Kolkata was home to an estimated 50,000 Chinese nationals. In those simpler times, there was no need for passports and visas, and skilled people could migrate to wherever they found employment.

The Chinese in India came from all over the Middle Kingdom — Canton (now Guangdong) in the south; Hupeh (Hubei), a central province; the Hakka, who were originally from the northern provinces, but later migrated all over China; and Shantung (now Shandong), an eastern province.

But almost 200 years after large-scale migration of Chinese began to India, the community has dwindled significantly. According to Tulun Chen, Mumbai-based chairman of the Maharashtra Chinese Association, there are just around 3,500 Chinese in Mumbai, down from an estimated 15,000 in the mid-1960s.

_“The Chinese are very few in number now, as a matter of fact, up to 1961 they were good in number, and after the Chinese War they were detained in, or sent to concentration camps to Devlali, Ahmednagar, Ahmedabad and so many other places. The ones who remained left for Hongkong, Canada and so many other places.

Before 1961, you could see a lot of Chinese on the roads, and is you saw one, you would see that they would wear there one style of clothes, Chinese style clothes, and the child would be behind the back and the foot size would be very very small because the Chinese said that if you are beautiful, it means you have very small feet."_

The temple now has become a bit famous, because now people are talking about it, newspapers are covering it, the festival is covered, and every year is the year of a different animal in the Chinese religion, which is celebrated accordingly. Most of the Chinese today are working as hairdressers, or working in a restaurant.

Mazgaon Interviews – Fakhruddin and Khateeja Merchant

Fakhruddin and Khateeja Merchant are both residents of Mazgaon. They are also my grandparents and the primary reason for initiating this project. They both narrate an account of their lives, their childhood, schooling, the socio-political situation of growing up in pre-independance India, the economic struggles of raising a family, and Mazgaon as the anchor of their lives since the last 40 years.

Mathar Pacady Interviews – Aunty Lavina and Uncle Martin

Aunty Lavina and Uncle Martin, both residents of Mathar Pacady speak about their lives and family; community and the need to defend the collective history of Mathar Pacady, a place they call home.

Mathar Pacady Interviews – Mr. Julius Valladares

Mr. Julius Valladares, a resident of Mathar Pacady speak about his father; family history and roots; and his own journey of growing up, working and building a community in Mathar Pacady, a place he calls home.

Mathar Pacady Interviews – Aunty Tessi

Aunty Tessi, a resident of Mathar Pacady speaks about her life, her history and the history of Mathar Pacady, a place she calls home.

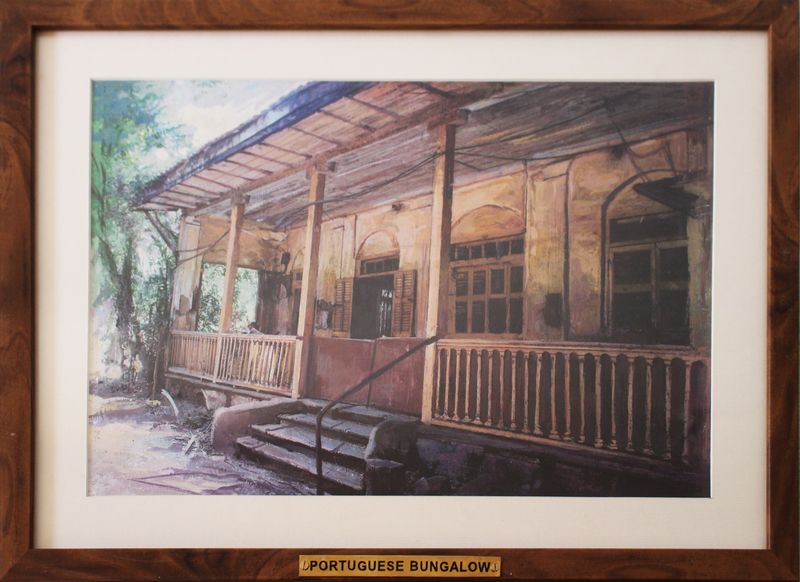

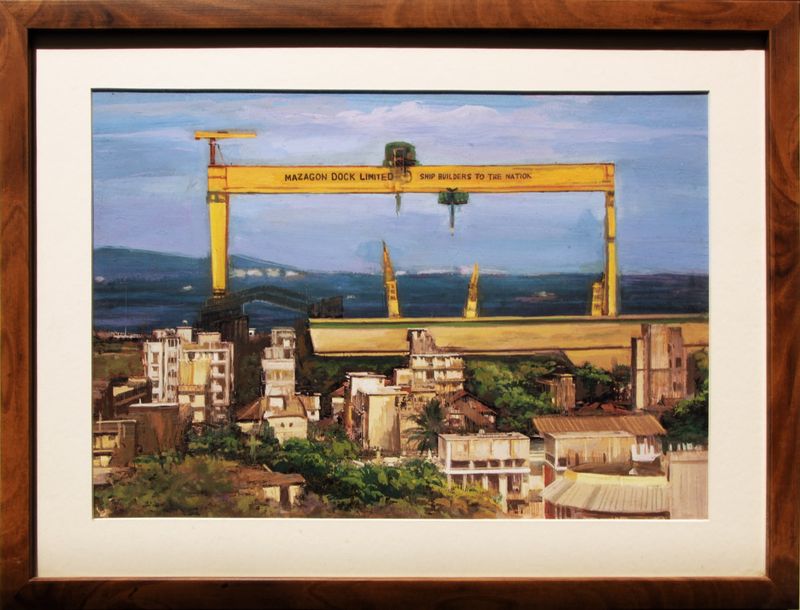

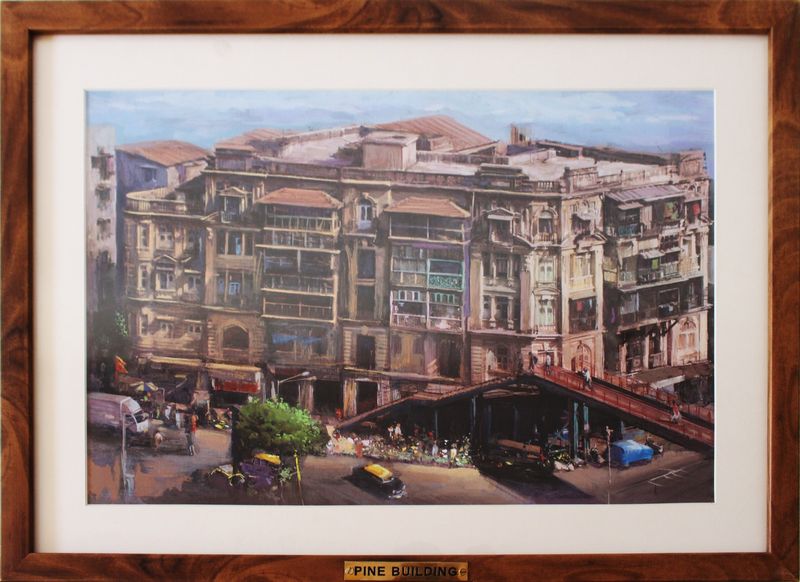

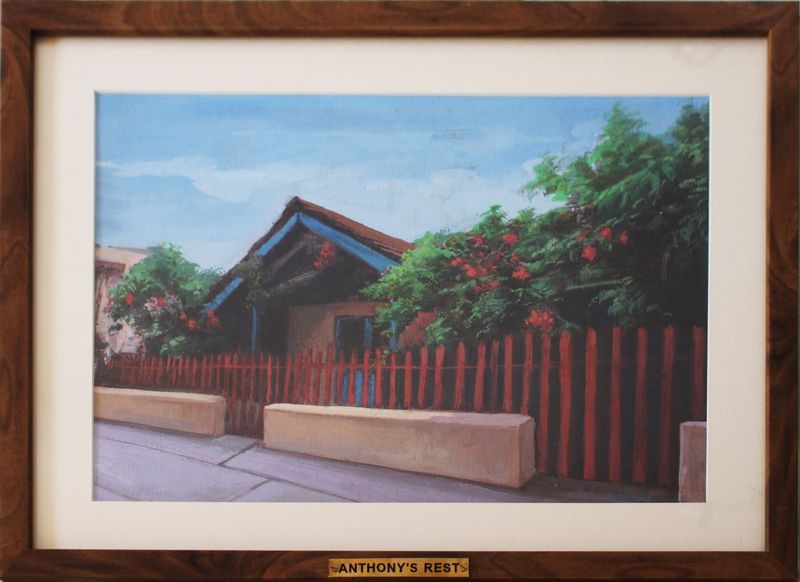

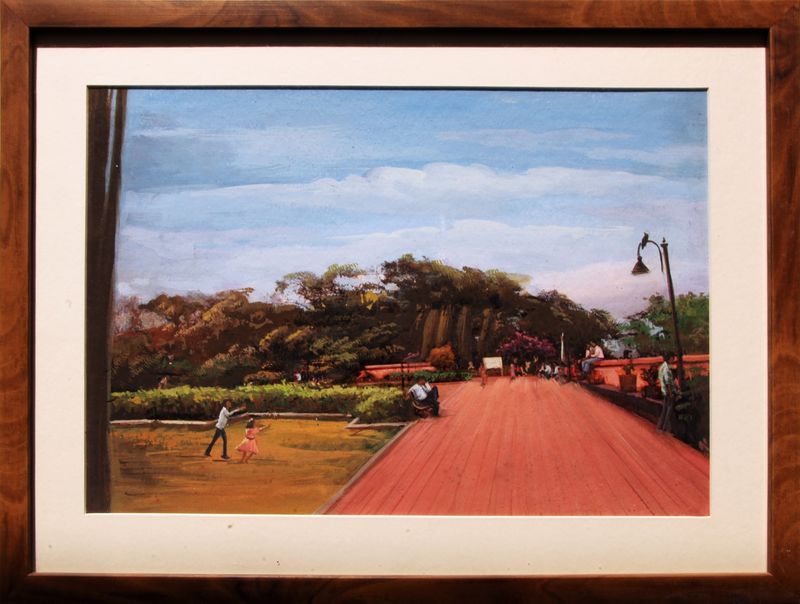

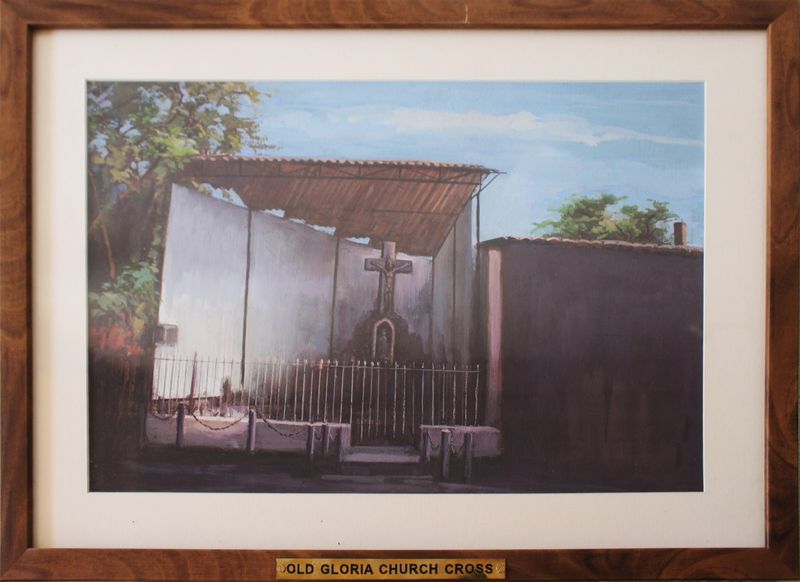

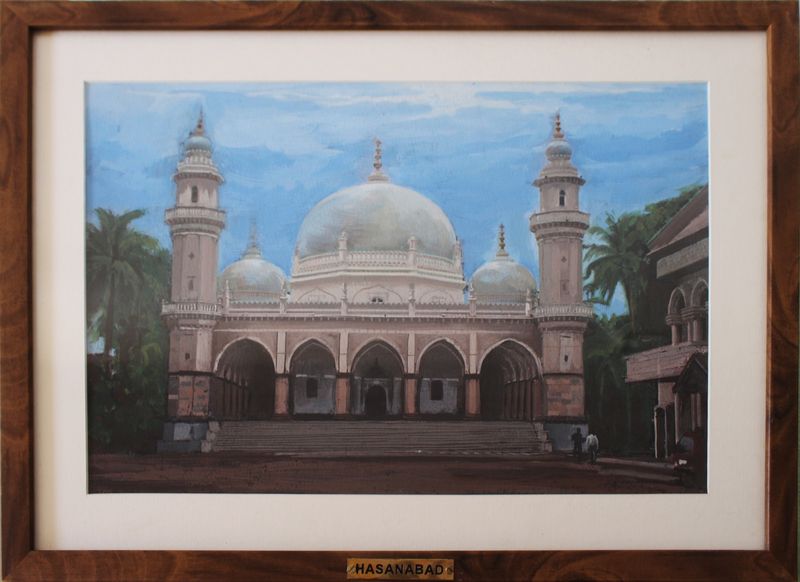

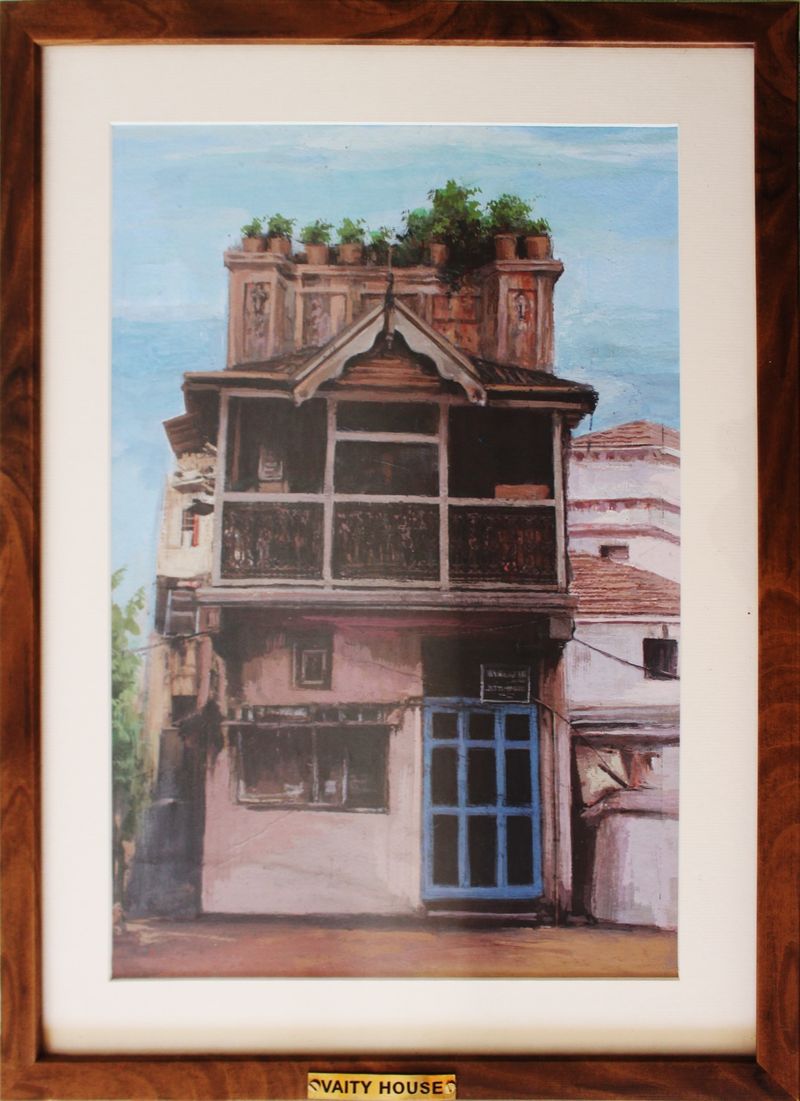

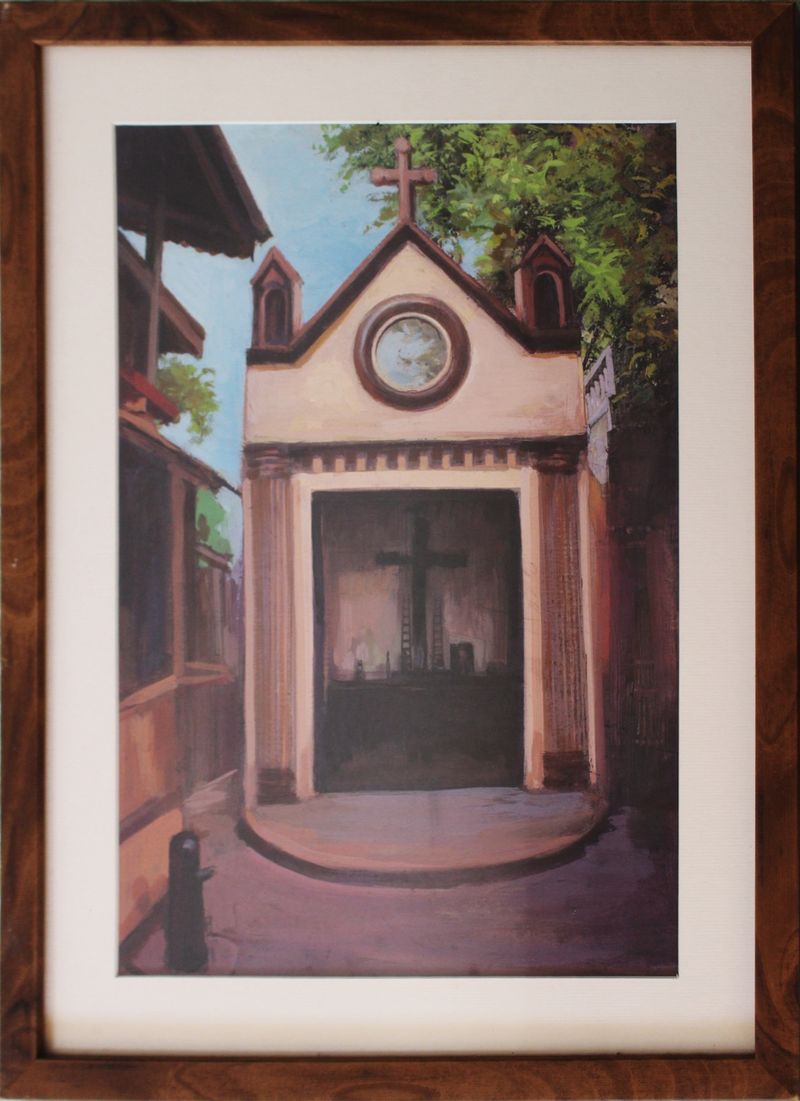

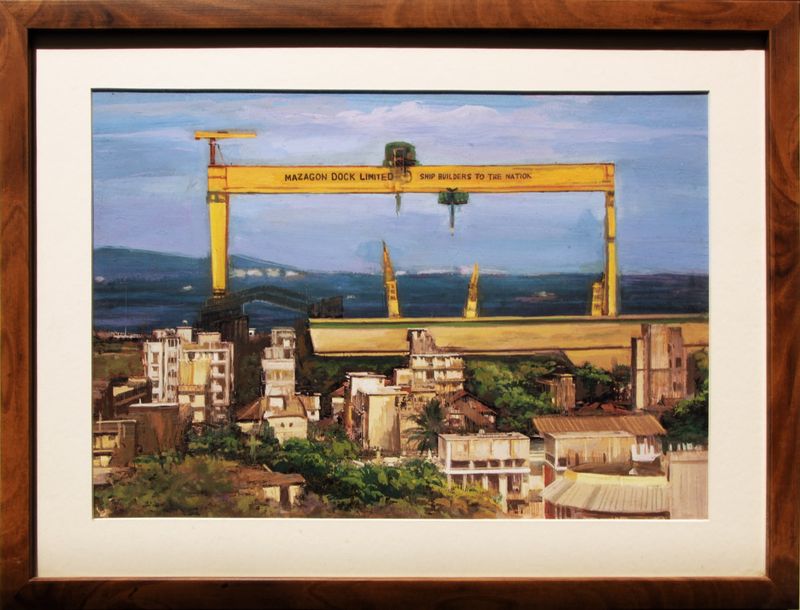

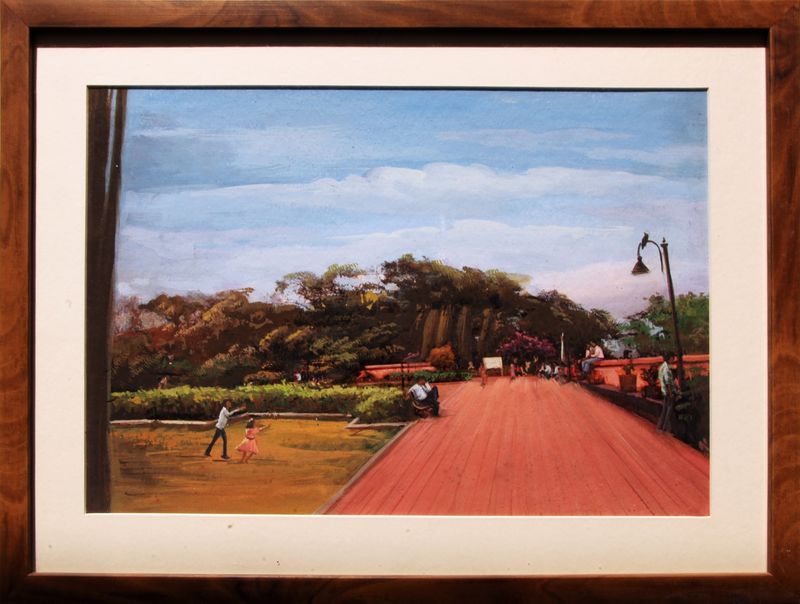

Paintings

The Paintings of Iconic landmarks of Mazgaon were commissioned by the artist as part of the project SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE, exhibited at Clark House, Mumbai.

The images were painted by Narendra Dewoodkar, a retired banner-painter from Mazgaon living in Vashi, Mumbai.

Paintings for SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE were commissioned to be made in a ‘Museum style’ referring to colonial paintings of Mumbai.

Making Space

curated by Saloni Doshi, Sakshi Art Gallery, Mumbai

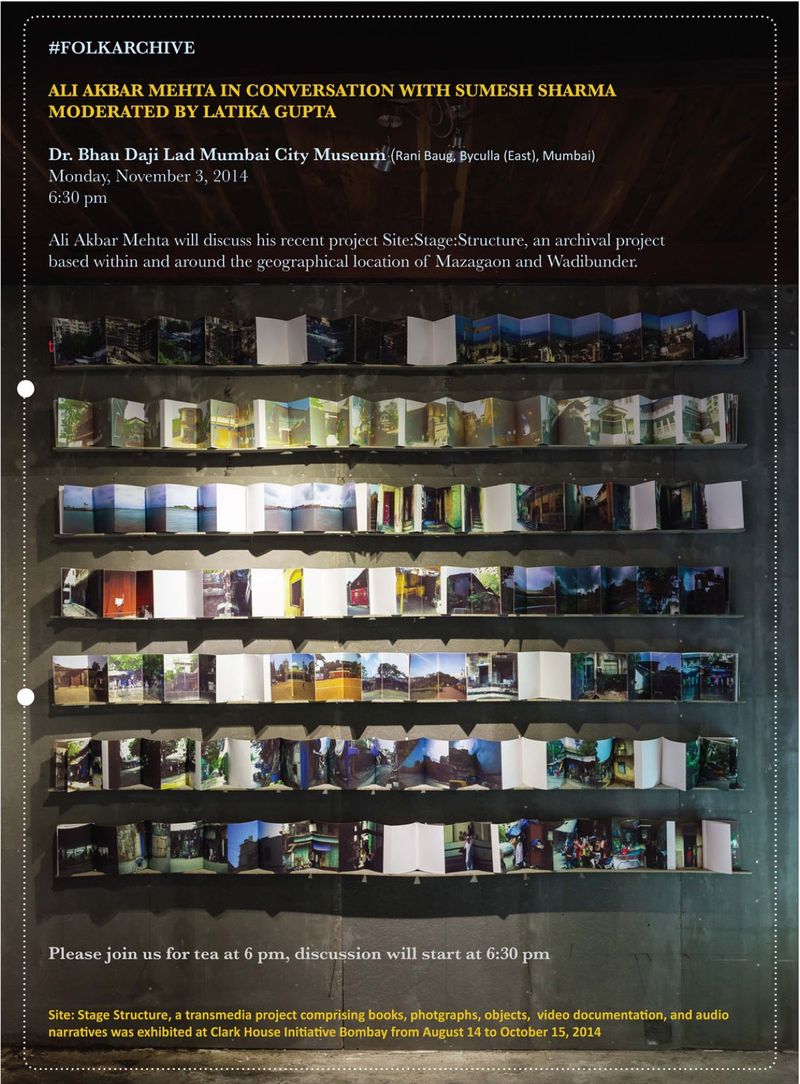

FOLKARCHIVE: Ali Akbar Mehta

in Conversation with Sumesh Sharma, moderated by Latika Gupta, Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Museum

An artist talk and presentation about Site : Stage Structure, and a subsequent conversation between Artist Ali Akbar Mehta, curator and director of Clark House Initiative Sumesh Sharma, and writer Latika Gupta.

Memory and the Maximum City

“In this talk held at the Godrej India Culture Lab on 9th January 2015, Anusha Yadav (founder of the Indian Memory Project) and Dr. Indira Chowdhury (President of the International Oral History Association) took the audience on a nostalgic journey of the city’s past using sound, photographs and much more. Artist Ali Akbar Mehta who displayed his exhibit titled ‘Site: Stage: Structure’ at the event was also part of the Q&A that took place after the presentations.”

Memory and Maximum City was one of my first talks as an artist. Here I presented some of the work shown during SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE, a transmedia archival installation of my four year engagement with Mazgaon and its several microcommunities. At this talk I spoke about the process of how my journey with this project began and in the subsequent conversation with members of the audience and fellow speakers, discussed the importance of alternative methods of history-building and the importance of oral histories.

Odes and Inquisitions: Sino-Indian Connections in Recent Indian Art

Essay by Ryan Holmberg

The Joseph Batista Gardens is one of the pleasantest places in Mumbai. Sitting atop a hillock, the garden park literally lifts you out of the noise from which even the surrounding neighborhood of Mazagaon, sedate by Mumbai standards, cannot escape.

To the north and west one gains a distinct view of the many mildew-stained high-rises that contribute to one of the highest population densities in the world. To the south, one sees rows upon rows of warehouses and train sheds. And to the east, a clear view of the city’s historical raison d’etre: Mumbai harbor, populated now with freight and naval ships, once open a time with frigates and opium clippers. It is not a picturesque view, for towering in the middle is a massive, yellow gantry crane inscribed with the words “Mazagaon Dock Limited, Shipbuilders to the Nation.” As advertised, this is India’s top shipyard, creating warships and submarines for the Indian Navy, offshore platforms for the oil industry, and tankers and cargo carriers for commercial shipping.

The site of Mumbai’s former Chinatown, centered on Nawab Tank Road, lies in the crane’s shadow. The dockside location reminds one that the basis of the overseas Chinese community in India, like in most places across Asia, was the centrality of China in international maritime trade in the early modern and colonial eras. Until the eighteenth century, Mazagaon was hardly more than a Portuguese fort surrounded by fishing villages. Both pleasantly verdant and conveniently adjacent to one of the best natural harbors in Bombay, the place was bound to change when Zoroastrian Parsi merchants and the East India Company made Bombay the new commercial center of Western India. By the mid nineteenth century, Mazagaon had become a fashionable suburb for Europeans and Parsi merchants, populated with many churches, private villas, and even a couple of luxury hotels. The shipyard dates back to the early nineteenth century. That is where the Chinese worked, reportedly mainly as nut and bolt fitters. What remains of that community, like the much larger one in Kolkata, is composed primarily of Cantonese, Hakka, and Hupei – which is to say, ethnic groups from the Pearl River Delta area and the main inland areas impacted by the opium trade that was developed by the Portuguese and the British in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

While Kolkata’s Chinatown holds on, Mumbai’s has been almost lost to oblivion. It registers so weakly in the city’s memory that even most lifelong Mumbaikars have never heard of it. Even at its height, Bombay’s Chinatown paled in comparison with that in Kolkata, which accounts for more than 90 percent of the country’s Chinese-Indian population. One has to dig for mention of Chinese residents in histories of colonial Bombay. When they do appear, they are merely one name in the colorful and multilingual crowd of traders and immigrants from across Asia, Africa, and the Middle East that made Bombay famous as the most cosmopolitan place in the Orient. “Chinese with pig-tails; Japanese in the latest European attire; Malays in English jackets and loose turbans; Bukharans in tall sheep skin caps and woollen gabardines,” closes Commissioner of Police S. M. Edwardes in his account of the ingredients of Bombay’s melting pot streets in the first decade of the twentieth century. Also in “certain clubs in the city where a man may purchase nightly oblivion for the modest sum of two or three annas” – which is to say, in the opium dens –“the proprietor of the club may be a Musalman; his patrons may be Hindus, Christians or Chinese.” Intoxication, Edwardes observes, overcomes “distinctions of race, creed and sovereignty” – not unlike, say, money and commerce did in the street. But when the sun went down (or, if you were an addict, when the sun came up), Bombay’s various ethnic groups returned to homes in communities that were more often than not segregated from one another.

None of this I would have known or bothered to look into had it not been for Ali Akbar Mehta’s Site : Stage: Structure (2013-14), a show at the Clark House Initiative, a quasi-non-commercial space in south Mumbai. A converted antiques shop of odd dimensions, tucked away spaces, and personal odds and ends, the Clark House tends to make everything installed in its space look like a cabinet of curiosities. Mehta’s Site : Stage : Structure – an impressionistic and sentimental survey of the neighborhood through a mix of video documentary, photographs, and personal knickknacks – appeared to be that by design.

The focus of the installation was on the personal memories of the artist’s own grandparents and grandaunts and granduncles, all Bohra Muslims (another famed merchant community) who have been living in the neighborhood since the early twentieth century. They talk through video interviews about their daily lives, and about their family business of manufacturing fishing hooks, physical samples of which hang on the wall. There were also reflections of a less personal sort, and these were aimed at capturing the historical traces of Mazagaon’s slowly disappearing cosmopolitanism. Three fat photobooks focused on aspects of the neighborhood’s buildings and people. There were also photographs, taken by Mehta and hand-colored by a painter of movie hoardings hired by the artist, of the few surviving churches, crucifixes, and bungalows that once crowded this originally Portuguese settlement. In the same series was also an image of the giant crane at Mazagaon Dock, as well as one of the nondescript pink façade (beige in reality) of a three-story building that houses, on its second floor, the only distinctive remnant of the area’s Chinatown: the Daoist Kwan Tai Shek temple, dedicated to Guan Yu, the famous general of the Three Kingdoms period. It was reportedly built by Cantonese sailors in 1919. A Buddhist temple to the bodhisattva Guanyin was established on the building’s ground floor in recent years.

In another room at Clark House, Mehta had assembled images and objects related to the Kwan Tai Shek temple. On a shelf in the corner were a handful of ritual items, including cups and an incense burner, and figurines from Journey to the West. Pinned upon the wall behind them was a grid of sheets of silver-painted joss paper, burned to send wealth to deceased ancestors. A cabinet in another corner of the room contained various Chinese vessels. Some of the displayed objects were culled from the temple and its caretaker’s home. Others were fashioned by the artist in a makeshift manner (simple canisters splashed with red paint, for example) similar to that used at the temple itself to create facsimiles of items not available in Mumbai

The centerpiece of the installation was a twelve-minute video. It featured artfully shot details of things like the temple’s bright red ceiling, burning incense, and armored Daoist gods. Some information about the temple’s history and its rituals are given in the voiceover, provided by the temple’s jaunty caretaker in a comically round accent. “No way, not while I’m alive,” he says, responding to an unheard question of whether the temple will be dissolved and the land sold. Yet his defiance, and the fact that on most days the temple stays locked and unused, raises the specter that perhaps this generation of Chinese-Indians will be the last to stand up for tradition.

Granted, the Chinese settlement was only one part of Site : Stage : Structure. But as the installation overall could have benefited from a clearer mapping of the neighborhood’s shifting demographics, so the Kwan Tai Shek component might have foregrounded why Bombay’s Chinatown has been reduced to fragments. In 1962, during the Sino-Indian War, many Chinese-Indians, not unlike Japanese-Americans after Pearl Harbor, were either deported if they didn’t have Indian citizenship or sent to internment camps in Rajasthan and Gujarat if they did. Returning to their homes after the war ended, many found their property and businesses damaged or confiscated. In the spring of 1963, the PRC sent ships to India to repatriate those who wished to relocate to China. Others moved on their own to Western countries, many to Canada. The exodus continues to the present, with growing business opportunities throughout Asia, including China of course. Many of those who are educated abroad choose to stay on in those countries.

Though the internment camps and resulting outmigration are noted in a few scholarly texts, no historian has undertaken a full study. This episode was made known to a wider public a few years ago through Rafeeq Elias’s The Legend of Fat Mama (2012), a documentary for the BBC about Kolkata’s shrinking Chinatown. The story Elias tells of persecution, marginalization, and disappointed emigration applies also to Mumbai, judging from the extensive wall text at Mehta’s Clark House installation. “According to Tulun Chen, Mumbai-based chairman of the Maharashtra Chinese Association,” reports Mehta from one of his many interviews with the community, “there are just around 3,500 Chinese in Mumbai, down from an estimated 15,000 in the mid-1960s.” Those who remain are now third and fourth generation. If they have not disappeared into Indian society, they run hairdressers and Chinese restaurants, including some of the most famous in the city.

Sketch-like though it might be, Mehta’s project is the most focused attempt to document the history and fate of Chinese-Indians in Mumbai. Information about the community is otherwise available only in the form of spotty online travel and entertainment blogs. Some of the artists and curators associated with the Clark House conduct related forms of urban history and ethnographic research, though I have never seen anything at the gallery on the scale of Site : Stage : Structure. Such projects not only enrich Mumbai’s art scene by offering something other than aesthetic wall-hangings and floor pieces, or theory-laden group shows. They also contribute to the city’s self-knowledge as a place with a conflicted and tangled cosmopolitan past. In an era in which rightwing groups continue to insist on Mumbai narrowly as a Hindu Marathi city, counter-historical practices like Site : Stage : Structure serve much more than ethnographic curiosity.

– Ryan Holmberg

*

Ryan Holmberg is an art and comics historian. After receiving his PhD in Japanese Art History from Yale University in 2007, he taught at the University of Chicago, City University of New York, and the University of Southern California. He is a frequent contributor to Art in America, Artforum, Yishu, and The Comics Journal, and is editor of two lines of translated manga from PictureBox, Inc. in New York: Ten Cent Manga, which focuses on the impact of American comics and mass entertainment on Japanese manga, and Masters of Alternative Manga. As a Sainsbury Fellow, Ryan is undertaking research that would eventually lead to the publication of his book project Garo and the Birth of Alternative Manga.

Ryan happened to walk in one fine day into Clark House, when he was researching a piece on Sino-Indian Connections in Recent Indian Art, which was published in the January/February 2015 volume of YISHU.

Chinese Fortunes and other Mumbai Memories

Mid-Day, 2015

Read here

Interview

by Godrej Culture Lab, Vikhroli, Mumbai

> What will be the focus of your talk; what will be the highlights?

SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE is an archival project based within and around the geographical location of Mazgaon and Wadibunder. It is a Transmedia installation integrating books, photographs, video documentation, audio narratives and heritage walks as a way of revitalizing memories and telling a history that is absent from the formal narratives. The highlight of the exhibition are the paintings, each presenting an important aspect of the city’s history and heritage; as well as photobooks of Mazgaon that document the changing demographic and visual identity of the space. The project maps Mathar Pacady, the remnants of Chinatown, a Bohri family’s apartment and Darukhana where ships are brought to be torn apart on the dry dock. Here I fight nostalgia by documenting it, recreating it through videos, conversations and staging ethnographic reconstructions of people’s homes.

> Tell us a bit about yourself and your work.

I make contemporary art, films, books, collaborate with robotic engineers, computer programmers, musicians, writers, theatre and film makers and aim to found processes that would leave deep impacts on contemporary culture, technology and knowledge.

Some of the mundane activities that I have been a part of are ‘Ballad of the War that Never Was, and other Bastardised Myths’, a solo exhibition of drawings, paintings and digital works, held at Tao Art Gallery, Mumbai in 2011; as well as recent group exhibitions at Tao Art Gallery, Mumbai; Art Heritage, New Delhi; and Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, Mumbai

> What is the importance of memories especially in an urban set-up?

The Project is a focused attempt to document the history and the present conditions of the people of Mazgaon. They contribute to the city’s self-knowledge as a place with a conflicted and tangled cosmopolitan past. Such projects enrich Mumbai’s art scene by offering something other than aesthetic wall-hangings and floor pieces, or theory-laden group shows. In an era in which rightwing groups continue to insist on Mumbai narrowly as a Hindu Marathi city, counter-historical practices like Site : Stage : Structure serve much more than ethnographic curiosity.

> Do memories matter today; how are they relevant at a time when things are changing very fast?

Memories matter in any day and age – I believe in the saying, “Those who forget history, are bound to repeat it”. In the context of the city and its people, the easiest thing would be to forget people who live beyond the perimeter of our immediate vision, but in doing so we condemn ourselves to be forgotten by others.

How many of us know the basic history of Bombay? Does it matter? Does it matter whether we knew or not what happened? How important is it to know that Bombay Docks started in 1735 or that Tarla House became J.J. hospital or that a structure such as Hasanabad exists, or the story of Pine building. At the end of the day it doesn’t really matter. But what is important is that there is a sense of identity that we’re losing and that reflects in the way we live; it reflects in how we conduct ourselves; and it is reflecting in the way Mazgaon is changing. The experience of Mazgaon changing through time and space is what is seen in the exhibition.

> How can art/urban planning/science help preserve memories?

Each aspect of the current exhibition can be extrapolated into a substantial body of work. At the same time this existing body of work needs to be disseminated beyond Bombay because it’s not the story of Bombay in itself, or the way Mazgaon has changed. Mazgaon is exemplary of the way several spaces/places in the country and the world are changing – silently, and without our knowing about it. It is like a falling teacup that we don’t see till it shatters. Fortunately Mazgaon and other places like that haven’t shattered yet. But they’re falling. It is up to us how soon we can look at them and how soon we can arrest that fall.

> How can the younger generations be motivated towards preserving memories?

Some of the most interesting responses to my work have been of people who have identified with the work and start sharing and talking about similar experiences within their own communities, families and friend circles. Slowly, people realise that not only can documentation be presented as ‘Art’, but that all kinds of memory can be important and valuable in the correct context.

I feel that the younger generations are increasingly aware of the importance of documentation. Our generation has produced more images in the last 10 years, than in the last 150 years combined. The focus will slowly move to being able to comprehensively understand what it is that we are documenting.

> What are you working on presently and looking forward to?

SITE : STAGE : STRUCTURE is an ongoing project. Slowly over a period of two years, it has developed through conversations with the local communities and groups. In the next phase of work, I want to focus on the present conditions and issues surrounding the people – property issues, entanglements with the political-builder nexus, issues of preservation and heritage, and developing awareness for the rich culture that exists in the forgotten backyard of the city.

As an ongoing project, I am currently seeking alliances and grants to make more than one copy of each book, which are 17 accordion fold books ranging from 20 to 40 pages, archiving the length and breadth of Mazgaon; and a set of 4 books, each focusing on a specific area of Mazgaon such as the soon-to-be-redeveloped 150 year old Dry Dock of Mumbai; the only Chinese Temple in Mumbai; and MatharPacady, a 300 year old Catholic ‘village’ surrounded by a political nexus and a dominating builder lobby.

I am interested in collaborative work environments and constantly looking for interested photographers, filmmakers and documentation artists to collaborate on future work and projects.

The BB Art Showcase: Ali Akbar Mehta

Interview by Khubi Amin Ahmed, for Be Beautiful India

Read here

The Possibility Of Alienation – Ali Akbar Mehta

Art Daily, 15.04.2014

Read here

Site Specific

Reema Gehi, Mumbai Mirror, 15.08.2014

Read here

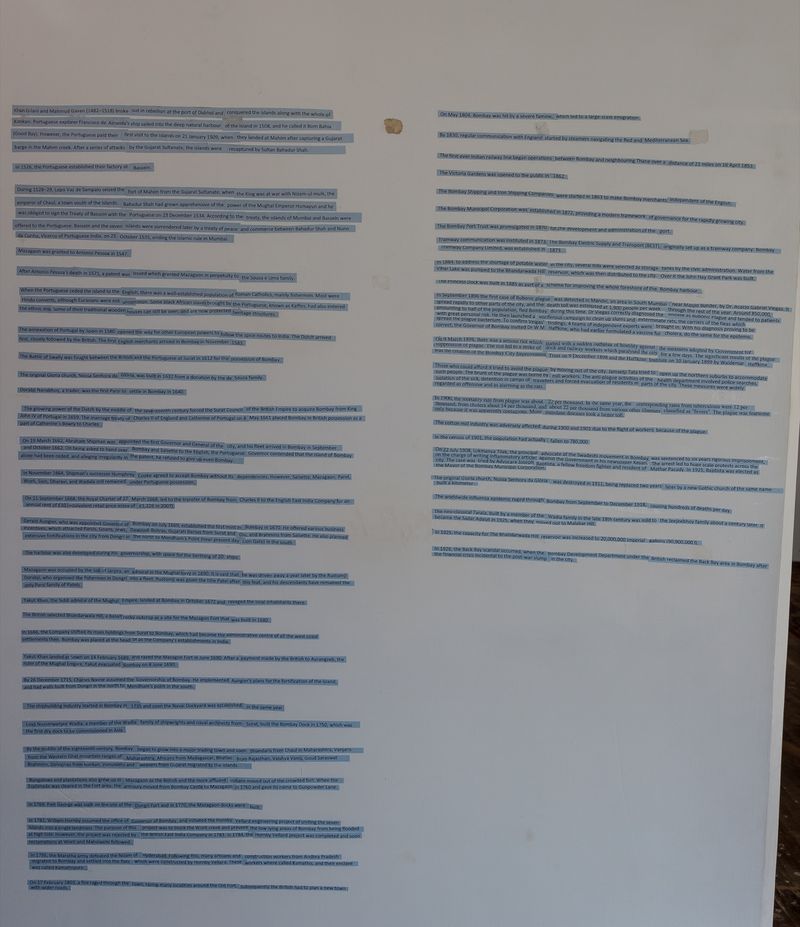

A select History of Mumbai

A select history of Mumbai through the lens of Mazgaon:

- After the end of the Bahamani Sultanate, Bahadur Khan Gilani and Mahmud Gavan (1482–1518) broke out in rebellion at the port of Dabhol and conquered the islands along with the whole of Konkan. Portuguese explorer Francisco de Almeida‘s ship sailed into the deep natural harbour of the island in 1508, and he called it Bom Bahia (Good Bay). However, the Portuguese paid their first visit to the islands on 21 January 1509, when they landed at Mahim after capturing a Gujarat barge in the Mahim creek. After a series of attacks by the Gujarat Sultanate, the islands were recaptured by Sultan Bahadur Shah.

- In 1526, the Portuguese established their factory at Bassein.

- During 1528–29, Lopo Vaz de Sampaio seized the fort of Mahim from the Gujarat Sultanate, when the King was at war with Nizam-ul-mulk, the emperor of Chaul, a town south of the islands. Bahadur Shah had grown apprehensive of the power of the Mughal Emperor Humayun and he was obliged to sign the Treaty of Bassein with the Portuguese on 23 December 1534. According to the treaty, the islands of Mumbai and Bassein were offered to the Portuguese. Bassein and the seven islands were surrendered later by a treaty of peace and commerce between Bahadur Shah and Nuno da Cunha, Viceroy of Portuguese India, on 25 October 1535, ending the Islamic rule in Mumbai.

- Mazagaon was granted to Antonio Pessoa in 1547.

- After Antonio Pessoa’s death in 1571, a patent was issued which granted Mazagaon in perpetuity to the Sousa-e-Lima family.

- When the Portuguese ceded the island to the English, there was a well-established population of Roman Catholics, mainly fishermen. Most were Hindu converts, although Eurasians were not uncommon. Some black African slaves brought by the Portuguese, known as Kaffirs, had also entered the ethnic mix. Some of their traditional wooden houses can still be seen, and are now protected heritage structures.

- The annexation of Portugal by Spain in 1580 opened the way for other European powers to follow the spice routes to India. The Dutch arrived first, closely followed by the British. The first English merchants arrived in Bombay in November 1583.

- The Battle of Swally was fought between the British and the Portuguese at Surat in 1612 for the possession of Bombay.

- The original Gloria church, Nossa Senhora da Glória, was built in 1632 from a donation by the de Souza family.

- Dorabji Nanabhoy, a trader, was the first Parsi to settle in Bombay in 1640.

- The growing power of the Dutch by the middle of the seventeenth century forced the Surat Council of the British Empire to acquire Bombay from King John IV of Portugal in 1659. The marriage treaty of Charles II of England and Catherine of Portugal on 8 May 1661 placed Bombay in British possession as a part of Catherine’s dowry to Charles.

- On 19 March 1662, Abraham Shipman was appointed the first Governor and General of the city, and his fleet arrived in Bombay in September and October 1662. On being asked to hand over Bombay and Salsette to the English, the Portuguese Governor contended that the island of Bombay alone had been ceded, and alleging irregularity in the patent, he refused to give up even Bombay.

- In November 1664, Shipman’s successor Humphrey Cooke agreed to accept Bombay without its dependencies. However, Salsette, Mazagaon, Parel, Worli, Sion, Dharavi, and Wadala still remained under Portuguese possession.

- On 21 September 1668, the Royal Charter of 27 March 1668, led to the transfer of Bombay from Charles II to the English East India Company for an annual rent of £10 (equivalent retail price index of £1,226 in 2007).[

- Gerald Aungier, who was appointed Governor of Bombay on July 1669, established the first mint in Bombay in 1670. He offered various business incentives, which attracted Parsis, Goans, Jews, Dawoodi Bohras, Gujarati Banias from Surat and Diu, and Brahmins from Salsette. He also planned extensive fortifications in the city from Dongri in the north to Mendham’s Point (near present day Lion Gate) in the south.

- The harbour was also developed during his governorship, with space for the berthing of 20 ships.

- Mazagaon was occupied by the Sidi of Janjira, an admiral in the Mughal navy in 1690. It is said that he was driven away a year later by the Rustomji Dorabji, who organised the fishermen in Dongri into a fleet. Rustomji was given the title Patel after this feat, and his descendants have remained the only Parsi family of Patels.

- Yakut Khan, the Siddi admiral of the Mughal Empire, landed at Bombay in October 1672 and ravaged the local inhabitants there.

- The British selected Bhandarwala Hill, a basalt rocky outcrop as a site for the Mazagon Fort that was built in 1680.

- In 1686, the Company shifted its main holdings from Surat to Bombay, which had become the administrative centre of all the west coast settlements then. Bombay was placed at the head of all the Company’s establishments in India.

- Yakut Khan landed at Sewri on 14 February 1689, and razed the Mazagon Fort in June 1690. After a payment made by the British to Aurangzeb, the ruler of the Mughal Empire, Yakut evacuated Bombay on 8 June 1690.

- By 26 December 1715, Charles Boone assumed the Governorship of Bombay. He implemented Aungier’s plans for the fortification of the island, and had walls built from Dongri in the north to Mendham’s point in the south.

- The shipbuilding industry started in Bombay in 1735 and soon the Naval Dockyard was established in the same year.

- Lovji Nusserwanjee Wadia, a member of the Wadia family of shipwrights and naval architects from Surat, built the Bombay Dock in 1750, which was the first dry dock to be commissioned in Asia.

- By the middle of the eighteenth century, Bombay began to grow into a major trading town and soon Bhandaris from Chaul in Maharashtra, Vanjaris from the Western Ghat mountain ranges of Maharashtra, Africans from Madagascar, Bhatias from Rajasthan, Vaishya Vanis, Goud Saraswat Brahmins, Daivajnas from konkan, ironsmiths and weavers from Gujarat migrated to the islands.

- Bungalows and plantations also grew up in Mazagaon as the British and the more affluent Indians moved out of the crowded fort. When the Esplanade was cleared in the Fort area, the armoury moved from Bombay Castle to Mazagaon in 1760 and gave its name to Gunpowder Lane.

- In 1769, Fort George was built on the site of the Dongri Fort and in 1770, the Mazagaon docks were built.

- In 1782, William Hornby assumed the office of Governor of Bombay, and initiated the Hornby Vellard engineering project of uniting the seven islands into a single landmass. The purpose of this project was to block the Worli creek and prevent the low-lying areas of Bombay from being flooded at high tide. However, the project was rejected by the British East India Company in 1783. In 1784, the Hornby Vellard project was completed and soon reclamations at Worli and Mahalaxmi followed.

- In 1795, the Maratha army defeated the Nizam of Hyderabad. Following this, many artisans and construction workers from Andhra Pradesh migrated to Bombay and settled into the flats which were constructed by Hornby Vellard. These workers where called Kamathis, and their enclave was called Kamathipura.

- On 17 February 1803, a fire raged through the town, razing many localities around the Old Fort, subsequently the British had to plan a new town with wider roads.

- On May 1804, Bombay was hit by a severe famine, which led to a large-scale emigration.

- By 1830, regular communication with England started by steamers navigating the Red and Mediterranean Sea.

- The first-ever Indian railway line began operations between Bombay and neighbouring Thane over a distance of 21 miles on 16 April 1853.

- The Victoria Gardens was opened to the public in 1862.

- The Bombay Shipping and Iron Shipping Companies were started in 1863 to make Bombay merchants independent of the English.

- The Bombay Municipal Corporation was established in 1872, providing a modern framework of governance for the rapidly growing city.

- The Bombay Port Trust was promulgated in 1870 for the development and administration of the port.

- Tramway communication was instituted in 1873. The Bombay Electric Supply and Transport (BEST), originally set up as a tramway company: Bombay Tramway Company Limited, was established in 1873.

- In 1884, to address the shortage of potable water in the city, several hills were selected as storage tanks by the civic administration. Water from the Vihar Lake was pumped to the Bhandarwada Hill reservoir, which was then distributed to the city. Over it the John Hay Grant Park was built.

- The Princess Dock was built in 1885 as part of a scheme for improving the whole foreshore of the Bombay harbour.

- In September 1896 the first case of Bubonic plague was detected in Mandvi, an area in South Mumbai near Masjid Bunder, by Dr. Acacio Gabriel Viegas. It spread rapidly to other parts of the city, and the death toll was estimated at 1,900 people per week through the rest of the year. Around 850,000, amounting to half of the population, fled Bombay during this time. Dr Viegas correctly diagnosed the disease as Bubonic Plague and tended to patients with great personal risk. He then launched a vociferous campaign to clean up slums and exterminate rats, the carriers of the fleas which spread the plague bacterium. To confirm Veigas’ findings, 4 teams of independent experts were brought in. With his diagnosis proving to be correct, the Governor of Bombay invited Dr W M Haffkine, who had earlier formulated a vaccine for cholera, do the same for the epidemic.

- On 9 March 1898, there was a serious riot which started with a sudden outbreak of hostility against the measures adopted by Government for suppression of plague. The riot led to a strike of dock and railway workers which paralysed the city for a few days. The significant results of the plague was the creation of the Bombay City Improvement Trust on 9 December 1898 and the Haffkine Institute on 10 January 1899 by Waldemar Haffkine…

- Those who could afford it tried to avoid the plague by moving out of the city. Jamsetji Tata tried to open up the northern suburbs to accommodate such people. The brunt of the plague was borne by mill workers. The anti-plague activities of the health department involved police searches, isolation of the sick, detention in camps of travellers and forced evacuation of residents in parts of the city. These measures were widely regarded as offensive and as alarming as the rats.

- In 1900, the mortality rate from plague was about 22 per thousand. In the same year, the corresponding rates from tuberculosis were 12 per thousand, from cholera about 14 per thousand, and about 22 per thousand from various other illnesses classified as “fevers”. The plague was fearsome only because it was apparently contagious. More mundane diseases took a larger toll.

- The cotton mill industry was adversely affected during 1900 and 1901 due to the flight of workers because of the plague.

- In the census of 1901, the population had actually fallen to 780,000

- On 22 July 1908, Lokmanya Tilak, the principal advocate of the Swadeshi movement in Bombay, was sentenced to six years rigorous imprisonment, on the charge of writing inflammatory articles against the Government in his newspaper Kesari. The arrest led to huge scale protests across the city. The case was tried by Advocare Joseph Baptista, a fellow freedom fighter and resident of Mathar Pacady. In 1925, Baptista was elected as the Mayor of the Bombay Municipal Corporation.

- The original Gloria church, Nossa Senhora da Glória was destroyed in 1911, being replaced two years later by a new Gothic church of the same name built a kilometer.

- The worldwide influenza epidemic raged through Bombay from September to December 1918, causing hundreds of deaths per day.

- The neo-classical Tarala, built by a member of the Wadia family in the late 18th century was sold to the Jeejeebhoy family about a century later. It became the Sadar Adalat in 1925, when they moved out to Malabar Hill.

- In 1925, the capacity for The Bhandarwada Hill reservoir was increased to 20,000,000 imperial gallons (90,900,000 l).

- In 1926, the Back Bay scandal occurred, when the Bombay Development Department under the British reclaimed the Back Bay area in Bombay after the financial crisis incidental to the post-war slump in the city.

- The Sadar Adalat was taken over by the army, and then donated to the J. J. Hospital in 1943 after a fire. It was used as a staff hostel for a few years before it was demolished.

The Chinese in Mumbai

In 1820, Kolkata was home to an estimated 50,000 Chinese nationals. In those simpler times, there was no need for passports and visas, and skilled people could migrate to wherever they found employment.

The Chinese in India came from all over the Middle Kingdom — Canton (now Guangdong) in the south; Hupeh (Hubei), a central province; the Hakka, who were originally from the northern provinces, but later migrated all over China; and Shantung (now Shandong), an eastern province.

But almost 200 years after large-scale migration of Chinese began to India, the community has dwindled significantly. According to Tulun Chen, Mumbai-based chairman of the Maharashtra Chinese Association, there are just around 3,500 Chinese in Mumbai, down from an estimated 15,000 in the mid-1960s.

“The Chinese are very few in number now, as a matter of fact, up to 1961 hey were good in number, and after the Chinese War they were detained in, or sent to concentration camps to Devlali, Ahmednagar, Ahmedabad and so many other places. The ones who remained left for Hongkong, Canada and so many other places.

Before 1961, you could see a lot of Chinese on the roads, and is you saw one, you would see that they would wear there one style of clothes, Chinese style clothes, and the child would be behind the back and the foot size would be very very small because the Chinese said that if you are beautiful, it means you have very small feet.

The temple now has become a bit famous, because now people are talking about it, newspapers are covering it, the festival is covered, and every year is the year of a different animal in the Chinese religion, which is celebrated accordingly. Most of the Chinese today are working as hairdressers, or working in a restaurant. “

Sadly, while bustling Chinatowns can be found in many parts of the world — including the US — in India, they are on the decline. Mumbai does not have a Chinatown as it did at the time of Independence. The Chinese came to Mumbai in the early part of the 19th century settled around the Mazgaon docks area in south-central Mumbai, and established a temple (the Kwan Tai Shek) and a cemetery. By the 1850s, the Chinese moved to other localities, including Byculla and Kamathipura. The latter became a notorious red light district, and is today one of the largest and oldest in Asia.

“There used to be a Chinatown in Shooklajee Street, where a lot of Chinese were staying; and if you go to Grant Road or to Falkland Road, there were a lot of Chinese dentists, now you don’t see them anymore. Only one or two are there, and there children have also become dentists, and they speak very good Hindi and Marathi; They have blended themselves very well, but you can make them out because they look different from us. “

Tangra in east Kolkata — which used to house over 350 tanneries — was once the most vibrant Chinatown in India. Today, Tangra has less than a quarter of its original Chinese population, while Shuklaji street has just a handful of Chinese families living there.

The Chinese-Indian community has traditionally specialised in a handful of professions, and even today most of the surviving members can be found in these crafts: foods and beverages (restaurants), dentistry, hair salons and shoemaking.

Says Ryan Tham, 27, a descendant of a prominent Chinese-Indian family: “There are about four families in Mumbai that run Chinese restaurants: the Wangs, the Chens, the Nankings and the Thams.”

Tham’s grandfather was born in Kolkata, and moved to Mumbai about 60 years ago. In 1962, he launched Kokwah, the first cabaret venue in India. Later, he opened the Mandarin, near the Gateway of India. His son Henry, who married a Bengali, sent his two sons — Ryan and Keenan — to Australia for higher studies. For several years, the family also ran the famous Thams salon, near the Taj Mahal hotel. Henry and his two sons now run Henry Tham, a fine-dining resto-bar in Colaba.

“We have been in the food and beverages business for the past 50 years,” explains the young Tham, who is often seen in celebrity circles and exclusive parties. “But I consider myself more Indian than Chinese. I am fluent in Hindi and Marathi and completed my schooling in Mumbai.”

Agnes Chen is another third-generation Chinese-Indian who feels more Indian than Chinese. Born in Kolkata, she was educated at the Loreto Convent and is fluent in Bengali, English, Hindi and French. “We are Chinese genetically, but in all other respects we are Indian,” says Agnes, who moved to Mumbai 13 years ago. “About 70 per cent of the younger generation Chinese-Indians have migrated to countries like Canada, the US and Australia,” explains Anges.

“I was too busy with my career and did not get the time to migrate,” she smiles. A hairstylist and dresser, she has worked for several multinationals, including L’Oréal, Procter & Gamble and Wella. She has lived in London and Paris, travelled across the world organising hair fashion shows, and has also trained over 10,000 hairdressers.

Today, she runs her own hair salon, Butterfly Pond, located in the over-100-year-old heritage building, Royal Terrace. Agnes points out that the overseas Chinese community is usually very enterprising, and most Chinese-Indians have set up their own businesses. Unlike many Chinese-Indians, she entered into an arranged marriage with another Chinese from Kolkata. Her nine-year-old daughter, a fourth-generation Chinese, was born in Mumbai.

Edward Wang, another young third-generation Chinese-Indian, is also extremely busy, expanding and modernising the restaurant — China Garden — which his father started in Mumbai. What does he think about young Chinese in India and their social interactions? “I don’t have a single Chinese friend, though I have a few acquaintances,” explains the 32-year-old. According to him, there is an increasing trend of Chinese marrying Indians

“Two sons of one my employees married Indian girls. Another employee’s son married a Nepali girl,” says Wang, who is single. His father, Nelson Wang, started life as a shoemaker in Hyderabad. He came to Mumbai with less than Rs50, and began working at a restaurant. He pioneered the concept of Indian-Chinese cuisine, creating dishes like Chicken Manchurian. Other restaurateurs have honed these skills, churning out meals like Gobi Manchurian, Chinese-bhel and chilli-fried tofu.

While many young Chinese-Indians have chosen to migrate to the West or Australia and New Zealand, there is a clutch of professionals who continue to thrive in India and have no plans to leave the land their forefathers made their home 200 years ago.

The Origin of Kwan Yin or Miao Shan

There are many legends about the origin of Kwan Yin. This is one of the most popular. Once upon a time in 17th century China, there was a tyrant king named Miao Zhang who had no respect for religion. He had three daughters, of which the youngest was named Miao Shan. At the time of Miao Shan’s birth the Earth trembled and wonderful fragrance of flower blossoms sprang up around the land. The people of the kingdom said that they saw the signs of a holy incarnation on her body…

Miao Shan grew up to be kind and generous and was loved by all. When Miao Shan got older the king wanted to find a husband for her, she told her father she would only marry if by doing so she would be able to alleviate the suffering of all mankind. The king became enraged when she heard of her devotion to helping others, and forced her to slave away at menial tasks. Her mother and two sisters admonished her to no avail. They were very mean to Miao Shan, making her work all day cleaning, sewing, and cooking. She tried her best to make them happy.

In desperation the king decided to let her pursue her religious calling at a monastery but ordered the nuns there to treat her so badly she would change her mind. She was forced to collect wood and water and tend a garden for the kitchen; they thought this would be impossible, since the land around the monastery was barren. To everyone’s amazement, the garden flourished, even in winter, and a spring welled up out of nowhere next to the kitchen. When the king heard about this miracle, he decided he was going to kill Miao Chan after all, the nuns who were supposed to have tormented her. But as his henchmen arrived at the monastery, a spirit out of a fog of clouds and carried her away to safety on a remote island. She lived there on her own for many years, pursuing a life of religious dedication.

Several years later, her father became seriously ill. His doctors, having tried everything, believed he would certainly die. Just as everyone was about to lose hope, a monk came to visit the king. The monk told the king he would cure the monarch but he would have to grind the arms and eyes of one free from hatred to make the medicine. The king thought this was impossible, but the monk assured him that there was a Bodhisattva living in the king’s domain who would gladly surrender.

The King sent an envoy to find this unknown Bodhisattva. When the envoy made the request Miao Shan gladly cut her eyes and severed her arms. The envoy returned and the monk made the medicine. The king instantly recovered. When the king thanked the monk, the chastised the king by saying, “ You should thank the one who gave her eyes and arms.” Suddenly the monk disappeared. The believed this was divine intervention and headed to with his family to find and thank the unknown Bodhisattva. When the royal family arrived, they realized it was their daughter Miao Shan who had made the sacrifice. Sensing their presence, Miao Shan spoke, “Mindful of my father’s love, I have repaid with my eyes and arms.” With eyes full of tears and hearts full of shame, the family gathered to hug Miao Shan. As they did so, auspicious clouds formed around Miao Shan, the Earth trembled, flowers rained down and a holy manifestation of the Thousand Eyes and the Thousand Arms appeared hovering in the air, and then the Bodhisattva was gone.

To honour Miao Shan and her love and compassion, the royal family built a shrine on the spot, which is now known as Fragrant Mountain.

Shrikrishna Report

1.1 This is an area in which majority of residents are Hindus, but there are certain known pockets of Muslims. Communally sensitive areas which experienced previous communal trouble are Kalapani Junction, Sakhli Street, Junction of Meghraj Shetty Marg and Baburao Jagtap Marg, Tank Pakhadi Road, Hindustan Masjid, Sunder Galli, Tambit Naka, Paise Street, S–Bridge and Dhobighat.

1.2 On 7th December 1992, at about 1230 hours, trouble started near the Byculla Fire Brigade Station with an attack on the Mhasoba Mandir by a mob of Muslims. The Muslim mob damaged the temple and when this news spread, a Hindu mob collected near the Mhasoba Mandir and started throwing stones and other missiles at the Muslims who had gathered near Meghraj Street. The police intervened and resorted to firing to control the situation. The miscreants damaged not only the temple structure, but also the idol inside and ransacked the belongings of the temple’s priest who lived on the premises. On the same day, a Vithal Mandir situated on Meghraj Street was also damaged and the property of the priest living there was also ransacked. The property damage was estimated to be over a lakh of rupees.

1.3 At 2030 hours, on 7th December 1992, there were clashes between Hindu and Muslim mobs at Sundar Galli and Kalapani Junction. Stones were thrown by the miscreants from Patra Chawl side on B.J. Road.

1.4 On 8th December 1992 there were pitched battles between mobs of Hindus and Muslims in Tank Pakhadi, Transit Camp, Tambit Naka, Hindustan Masjid and Khatau Mill areas. During the melee one police officer, A.S. Sawant, was injured on his thigh by stone throwing and some of the miscreants in the Muslim mob attempted to snatch away the rifle of one of the constables. Police resorted to firing resulting in injuries to two persons.

1.5 During December 1992 the police registered six offences, out of which two pertained to the attack on the Mhasoba and Vithal Mandirs. The other four offences consisted of three attacks on Muslim properties and an attack on a rationing shop on 9th December 1992.

1.6 Trouble started in January 1993 with an incident of stabbing at Mominpura Patra Chawl at about 0100 hours on 7th January 1993 in which a Hindu was stabbed by unknown persons. At the same time, the news about incidents of stabbing, arson, and stone throwing occurring with alarming frequency in the adjoining jurisdictions of Dongri, Pydhonie, Nagpada and in Mahim heightened the communal tension in this area. The police managed to maintain an uneasy peace on 7th January 1993 and upto the evening of 8th January 1993.

1.7 From 2100 hours on 8th January 1993, riots erupted at BIT Chawls, Maulana Azad Road, Sakhli Street and Kalapani Junction. The trouble seems to have first erupted in BIT Chawls No. 12, 11, and 23. Though the police claim that the incident was one of a violent clash between armed mobs of Hindus and Muslims, the true picture seems to be different. According to the evidence of one of the Muslim victims, Mumtaz Rehman, the trouble in the BIT Chawls started at about 7.30 p.m. with the Hindu residents attacking Chawl No. 12 occupied by Muslims with stones, soda–water bottles and petrol bombs, shouting “Landyabhai ko maro”, “Pakistan ko bhagao” and “Bara number me ghuso”. Sixty–three out of the eighty tenements in Chawl No.12 are occupied by Muslims and the rest by Christians.

In the other BIT Chawls, the preponderant majority is of Hindus, though a few tenements are occupied by Muslims. When the stone throwing started, Mumtaz Rehman telephoned the Agripada Police Station to complain that the Muslim residents of BIT Chawl No.12 were being attacked by Hindus. The telephone was answered by an unidentified person in the police station who, on receiving the request for help, rudely replied, “Landybai Chup baitho, Abhi kuch nahi huva” and banged down the phone. Mumtaz then frantically phoned for help to some Muslim corporators of Janata Dal and some Muslim officers in the military. After about an hour or so, a police mobile came to BIT Chawl No. 2 with three constables and an officer. The main entrance of that chawl has a collapsible iron grill which had been shut and locked by the residents who feared for their lives. The police repeatedly rattled the collapsible iron grill, calling upon the residents of Chawl No.12 to open the lock.

According to Mumtaz, the Hindu miscreants in the surrounding chawls were standing around with swords and choppers in their hands. But instead of dealing with them, the police threatened the residents of Chawl No.12 that if they did not open the collapsible door they would be shot. By this time, some of the miscreants had cut off the telephone line, electricity line and water connection of Chawl No.12. There was also an attempt to set fire to Chawl No.12, which, according to Mumtaz, occurred in the presence of the police without the police taking any action. The miscreants set fire to two taxis and two motorcycles of Muslims, looted four gas cylinders from Muslim houses in Block No.11, kept them in front of Chawl No.12 and attempted to set fire to them. Major catastrophe was, however, avoided since the police took charge of and removed the gas cylinders.

The water, electricity and telephone lines were restored only on 9th January 1993 at about 1230 hrs, after the arrival of military personnel accompanied by plumbers. The police claim that the collapsible iron door had been connected to live electric wires as a result of which the police constable who attempted to open the collapsible door got an electric shock. The story appears apocryphal. Mumtaz says that the police were repeatedly rattling the collapsible door. The Senior Police Inspector’s evidence shows that no attempt was made to discover if the theory of electric current was true. As a matter of fact, at the material time the electric connection itself had been disrupted. Senior Police Inspector Tikam, says that he did not notice any electric wires connected to the collapsible iron shutter, nor did the police attempt to force open the said door.

A police picket was posted in front of Chawl No.12 and in the morning at about 6 a.m. the police managed to enter the building from a side entrance. This time the police were armed with electric testers and when they tested the iron grill of the shutter, it was not found electrified. There is also no mention of any of this story in the Station Diary of the police station, though Tikam admitted that this was a very serious incident and gall serious incidents must be noted in the Station Diary.

Sarwaribegum, resident of BIT Chawl No. 8, says that, at about 2200 hours on 8th January 1993, the miscreants repeatedly banged on her door and broke open the door to her tenement. She along with her two daughters–in–law and children was inside. One of the miscreants, Santosh Nagaonkar, started damaging the articles in the house and another placed a chopper on her neck and asked about the whereabouts of menfolk. The women pleaded for their lives, managed to run away and seek shelter in Prabhat Building. Sarwaribegam says that, when all this was happening, she saw the police standing 15 feet away from the building, doing nothing.

When she complained to the police about the attack on her chawl and requested action against the miscreants, the police asked her to go away. She made a complaint to the police station on 16th January 1993 narrating what transpired during the night of 8th January 1993. She denies the correctness of what is alleged to be her statement (Exhibit 550 (P)) and maintains that she had specifically given the name of Santosh to the police officer who took down the complaint. So much, for the reliability of the police records.

1.8 The Senior Police Inspector claimed that there were several instances of private firing upon the residents of Pathan Chawl (now known as Bhagwa Mahal) resulting in injuries to three Hindus, Chandrashekhar Bhiva Sawant, Sanjay Ramchandra Sawant and Prakash Keshav More. These three persons gave identical evidence that, because of fireballs thrown at Pathan Chawl by the Muslim residents of the adjoining building known as “80 tenements”, the Pathan Chawl caught fire. And when the residents of Pathan Chawl were running around to extinguish the fire, they were shot at from the 80 tenements Chawl. They also claimed to have identified the person firing at them as one Nasir Bakerywala.

1.9 That these three persons were injured by bullets is certain; it is doubtful whether they were injured in an incident of private firing. The material on record seems to suggest that probably they were injured in police firing, while participating in the riots, which they are now passing off as the result of private firing. Though each one of them claims to have seen Nasir Bakerywala firing at them, one says that the firing was from a pistol and another that it was from a big gun. None of them named Nasir Bakerywala in the police statements. The police have also submitted a supplementary report to the Additional Commissioner of Police (Crime) (Exh.569© giving full particulars of the incident in CR No.33/93. In that supplementary report these three are shown to have been injured in police firing.

1.10 The metamorphosis of ‘Pathan Chawl’ into ‘Bhagwa Mahal’ is also interesting. Though all others claimed that there was no connection between Shiv Sena and Pathan Chawl, Mohan Kadam Bahadur Lama, a resident of Pathan Chawl from 1969, who knew Prakash Keshav More, Sanjay Dattaram Sawant, Chandrashekar Bhiwa Sawant and Dattaram Vasant Narvekar, gives a different version. According to him, the name of Pathan Chawl was changed to Bhagwa Mahal when the Shiv Sena started moving about frequently. Someone from the Shiv Sena had come and said that Pathan Chawl should henceforth be called Bhagwa Mahal and, “since they said so, it is also called Bhagwa Mahal”. This obviously indicates that the residents of Pathan Chawl or Bhagwa Mahal were very much protagonists, if not activists, of Shiv Sena.

Lama’s affidavit was filed at the instance of one Tukaram Amre and another “fat police officer” was accompanying him. This Tukaram Amre was the person instructing the Shiv Sena’s counsel when the cross–examination was going on before the Commission and was identified by the witness Lama. Lama also said that, apart from him, Tukaram Amre had brought four or five persons to file affidavits and was accompanied by one fat police officer. This evidence leads the Commission to think that the story about private firing is a contrived one, put forward at the instance of the activists of Shiv Sena and the police, though the identity of the “fat police officer” is unascertainable.

1.11 Meherunnissa Mohammed Yakub Ansari (Exh.577) also says that from about 1930 hours on 8th January 1993, till about 1330 hours on 9th January 1993, there were continuous attacks on their chawl.

No.12. The attackers were all Hindus from BIT Chawls who kept shouting, “Landyabai ka ghar kidar hai” and knocking on her door. They were carrying choppers and other weapons. She is emphatic about what the police told her when she complained to them. Says, the witness, “I cannot forget during my entire life the words used by the police — ‘Pakistan chale jao; yahan kyon ate ho marne ke liye’”. After the Muslim residents had moved away to safety locking their houses, their houses were systematically ransacked and looted.

1.12 On 10th January 1993 riots erupted simultaneously at about 1030 hours near Fancy Market, Moreland Road, Hirve Chawl on Maulana Azad Road, Pathan Chawl on B.J. Road and Dhobighat. There was extensive arson and looting of property. In fact, the vicious nature of the riots can be gauged from the statistics given by the police themselves. About 200 Muslim families from Dhobighat area had abandoned their houses and fled to safety. Their houses were systematically ransacked, damaged, looted and subjected to arson. According to the police, in all about 200 incidents of arson and looting took place on 10th January 1993; in almost all cases the victims were Muslims.

1.13 There were crude attempts by the police to cover up the role of the Shiv Sena in the incidents of January 1993 :

(a) Though the Senior Police Inspector had filed particulars of the Mahaartis organised (Exhibit 514(P)), in which the number of Mahaartis were shown as having been organised by the Shiv Sena, he later on claimed that there was a mistake in it and filed another sanitized version in which it was sought to be maintained that the different Mahaartis were organised by different organisations, though the leaders of the Shiv Sena happened to remain present at the Mahaartis.

b) There was another attempt to underplay the role of four accused arrested in C.R. No.17 of 1993, who were reported to be Shiv Sainiks. Senior Police Inspector Tikam had made an endorsement in the case papers of C.R. No.17 of 1993 that the four accused persons arrested from BIT were Shiv Sainiks and that a report to that effect has been given to Assistant Commissioner of Police, Mehta of S.B.–I CID. When closely questioned about this endorsement, Tikam feigned lapse of memory. Daljitsingh Parmar, the investigating officer stated that the Senior Police Inspector Tikam must have got the information that the four accused were Shiv Sainiks and, though he made inquiries from public and interrogated the accused, he could not get confirmation of the said fact. He had even questioned the Shakha Pramukh of Shakha No.37 who stated that the four accused arrested in C.R. No.17 of 1993 were working along with Shiv Sainiks, but were not “authorised members” of Shiv Sena. No attempts appear to have been made to look into the records of membership or to cross–check the information given by the Shakha Pramukh. Daljitsingh Parmar conceded that if he had done such exercise he would have been able to ascertain whether the four accused were members of Shiv Sena and that it was a mistake on his part not to have done so.