Pudding Manifesto for Togetherness

part of EXPLORING HISTORICAL AND THEORECTICAL ROOTS

Seminar by Nora Sternfeld and Minna Henrikson January 11 – February 2, 2016

Whose History Is It Anyway? *

Pudding Manifesto for togetherness by Ali Akbar Mehta, Jernej Čuček Gerbec, Jonne Kauko, Martina Miño Perez

Proposal for Pudding Manifesto

Project Proposal by Ali Akbar Mehta

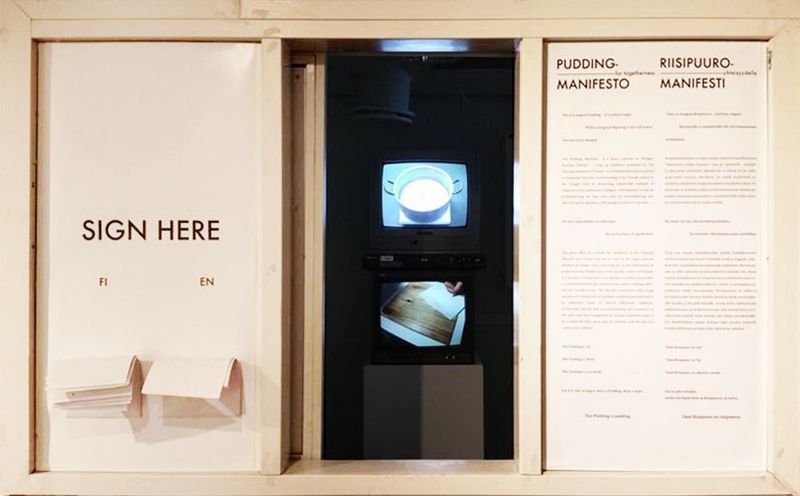

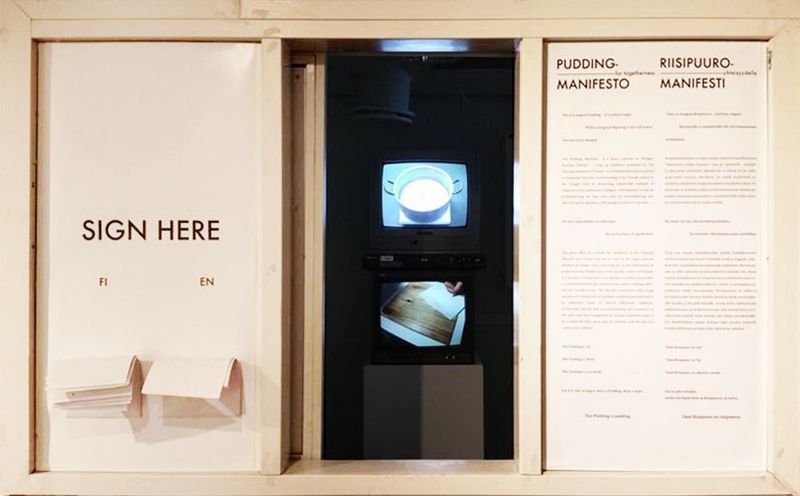

The Pudding Manifesto for Togetherness (2016) is a collaborative performance installation in which is embedded a manifesto that presents in satirical humour the benefits of consuming a ‘magical pudding’ that will change people, a pledge signing and a subsequent serving of Rice pudding. Rice pudding has a history spanning several civilisations and culture, and here we are creating a hybrid pudding based on Syrian and Finnish recipes, as a conjoining of two ways of eating and therefore a symbolic act of consumption becomes an innovative catalyst for the otherwise rhetorical discourse on refugee integration and assimilation into the homogeneous social soup.

Food has always operated in circulation between the local and the global, migration and resettlement and, with its power in defining and performing social meanings, served to construct notions of home and cultural otherness. Perhaps it can also create notions of togetherness. We don’t need politics of unification – we need politics of togetherness.

Rice Pudding is a dish made from rice mixed with water or milk and other ingredients such as cinnamon and raisins. Recipes can greatly vary even within a single country. Names of Rice Pudding in the world (alphabetical order):

- Arroz con leche,

- Arroz con dulce,

- Arroz en leche,

- Arroz doce,

- Arroz de leite,

- Arroz-esne,

- Banana rice pudding,

- Bubur Sumsum,

- Budino di Riso,

- Сутлијаш or Благ ориз,

- Сутлијаш/Sutlijaš,

- Сутляш or Мляко с ориз,

- Dudhapak,

- Firni,

- Grjónagrautur,

- Ketan hitam ,

- Kheer,

- Kiribath,

- Milchreis,

- Mlečni riž or Rižev pudding,

- Mliečna ryža,

- Moghli,

- Morocho,

- Muhalibiyya,

- Молочна рисова каша,

- Orez cu lapte,

- Payasam,

- Phinni/Paayesh,

- Pudding Orez,

- Pulut hitam,

- Ρυζόγαλο,

- Рисовый пудинг

- Risovwe pudding,

- Riisipuuro,

- Rijstebrij,

- Rijstpap,

- Risgrynsgröt,

- Risengrød,

- Risengrynsgrøt,

- Riz au lait,

- Riz bi haleeb,

- Riža na mlijeku

- Ryż na mleku,

- Shir-berenj,

- Shola-e zard,

- Şorbeşîr,

- Sütlaç,

- Sutlija,

- Sutlijas,

- Sylt(i)jash or Qumësht me Oriz,

- Tameloriz,

- Tsamporado,

- Teurgoule,

- Tejberizs, and

- Zarda wa haleeb.

The Manifesto for Togetherness

Whose History is it Anyway?*

Aalto University, 2016

January 11 – February 2, 2016

Pudding Manifesto, Video

The making of the rice pudding (Riisipuuro/Kheer) is overlapped by the audio of interviews of visitors to the exhibition “Refugee, Evacuee, Migrant” (Finnish National Museum, 2016).

During the interview, members of the audience are asked about their responses to the exhibition, their feelings towards the current refugee crisis, and their own memories of events of migration.

Pledge

As per the rules of the ‘Pudding Manifesto for Togetherness’, the members of audience wishing to participate, sign the pledge to uphold the manifesto.

Project Report

What is questioned: The Seminar started with explorations towards notions and strategies of nation building, The issue of living amongst each other and the issue of the perception of the Other, what does this create this ‘other’ imply, not philosophically but in a political and historical perspective. One particular example which became a central point of conversation and debate was the ‘Swastika’ and how the actions of the Nazi ideology has seized the imagination and the fundamental essence of the image/symbol and mutated it through its own actions to transform it into a signifier connoting an unforgettable and unforgivable event in human history. Such a symbol becomes part of the collective history of an entire people, and becomes the shared collective experience of humanity.

We confronted what is chosen to be remembered and what we choose to forget, specifically in the Finnish context – The paradoxical relationship that Finland has with colonialism, of historically being in the role of the victim and now becoming the perpatrator, while also writing its history from an ‘Exceptionalist’ approach, cooperation with nazi-Germany and occupation of Russian territory during The second World War and denying its direct and indirect participation in colonialist and racist international projects.

During the second day of our seminar, we visited the Finnish National History museum, where the Pop-up exhibition ‘Migrant, evacuee, Human’ was on display. The exhibition aims to present a transparent and clear understanding of the Finnish context in the ‘Refugee Crisis’ by showcasing examples of various Finnish and other regional communities in ambiguous states of arrival/departure. The problematic nature of the exhibition resides in its oversimplification and obvious smoothing over of the projected idea of the ‘Crisis’: Instead of relevant informations pertaining to the complex histories of war and migration, the exhibition offers comfortable examples of integration and usefulness of refugees within the larger Finnish social framework.

What is furthermore implicit in this presentation is the fact that by mounting such an exhibition the museum – as an official “national” institution – situates the nation as culturally “open” in the larger European Union (while its border politics are not open at all). It also gives a cursory nod to having ‘dealt with’ the topical subject of the Refugee crises. To put it in a nutshell: In an educational and enlightening mode, the exhibition provides nothing, while having given the sense of feeling a false nationalistic pride.

In the post-Cold War world, decades after the conception of the Europa Utopia project the ‘European Union’ – “United in diversity”, – comes under direct threat by its own actions – the lack of sympathy towards close to 20 million human beings. An ideological death of the founding principles, that can only be averted if its citizens realise that they have replaced the former motto with a new one, that borrows directly from the Nazi-period – ‘Europe for Europeans’.

This is presented in the patriarchal and hegemonic way the information is presented in the exhibition. Specifically, in the context of work produced, we questioned the Pop-up exhibition, its strategies of display, the way it sought to alienate the refugees in the guise of talking about them, and lastly, the choice of where it was displayed.

How was it followed:

We responded to this by first conceiving of an augmented exhibition, placed in the same space and time, overlapping the exhibition ‘refugee, evacuee, human’.

This exhibition, in its execution aimed to create a parallel virtual tour, using innovative technologies and the integrated smart devices. Using a proprietary ‘app’, we wanted to use augmented reality to overlap a counter exhibition as a way to subvert the existing exhibition and allow for a more participatory and integrated exhibition –to recreate the exhibition in the same format of the current exhibition, using key placements of photographs, objects and personal memories to allow for a unique socio-political intervention, rather than treating the idea of the exhibition as a static response to the world around us.

The act of creating this counter exhibition was to subvert the discourse and redirect it to the required channels – to create an archive of existing material and consolidate it to create a coherent understanding of unfolding events, and to create new contextual material through documentation and interviews of local people in Helsinki and surrounding cities.

The counter exhibition would have acted as constructive criticism ¬¬– enabling a new way of how we respond to future exhibitions. It will allow for community participation. By giving the audience the power to intervene, it would have made the exhibition not just an end in itsef but a means to disseminate information that actively leads to newer explorations.

This exhibition as a virtual augmented reality overlap is not limited to this particular exhibition, but as a template can be applied to other exhibitions in the future.

Steps + interventions:

Although, we initially responded to the exhibition, we felt that we outgrew the need to directly place ourselves into the exhibition. Time and resources also seemd inadequate to responsibly attempt an project of this magnitude. We decided to narrow our focus to a few specific aspects – We chose to react primarily to the idea that a space of a casual eating area was chosen to display a serious subject such as the refugee crisis. We reacted by inverting the methodology by emphasising the context through the act of eating, and by creating an active engagement of the subject of togetherness, through food, the act of integration of the recipes and the physical act of digesting it.

The Pudding manifesto thus becomes a collaborative performance installation in which is embedded a manifesto that presents in satirical humour the benefits of consuming a magical pudding that will change people, a pledge signing and a subsequent serving of Rice pudding. The pudding has a history spanning several civilisations and culture, and here we are creating a hybrid pudding based on Syrian and Finnish recipes, as a conjoining of two ways of eating and therefore a symbolic act of consumption becomes an innovative catalyst for the otherwise rhetorical discourse on (as well as the lack of ) refugee integration.

The Pudding manifesto is still a direct response to ‘Refugee, Evacuee, Human’ – a Pop up Exhibition presented by the National Museum of Helsinki.

This Pudding Manifesto offers to present the exhibition in the way we think it should be handled – with criticallity and a sensitive understanding of what the ‘Refugee Crisis’ really is all about – the socio-political conditions of Syria and the Middle East, and the right wing extremist agendas of ISIS that drives the innocent native citizens out of their country into the biggest Exodus since the Second World War. The apparent problematic that faces the European Union in the face of this crisis is what we would like to call ‘The Problem of Accomodation’. This particular problem of accomodation has been misrepresented by the hegemonic oligarchy of the First World as ‘The’ problem that required attention and compassion. In wake of this, the true problem is swept away under newly emerging issues of migration and the “clash of civilization”.

We felt that creating an independent manifesto as a proclamtion of ideology was not an end in itself, but required direct involvement and participation of those termed ‘refugees’ not just within the current crisis but also in other instances peppered within Finnish History. We sought words of empathy and solidarity from those who have suffered similar ordeals and experiences yet have manged to perhaps put it behind them and managed to corve a niche for themseles within the ‘mainstream’ Finnish society. We hoped to gather a fresh view on the subject.

To further this, we interviewed several Corellian refugees, and asked them to respond to the exhibtion in their own way. We also asked them to comment, if they wished, on what they felt about certain things within the exhibition that atleast disturbed our team – the lack of the historical contexts within each individual crisis as well as the lack of an understanding of what the current crisis is all about; and the objectification of the people in a way that reduces them to the stereotype of ‘refugee’.

These interviews’ audio is played along with the visual act of cooking the Pudding. This, along with the recording of the signature campaign pledging an allegiance towards the manifesto, became part of the documentation that followed the exhibition opening.

The documentation of our process has been one of the methods we used to approach the work. In addition to the interviews, we have some video material from our discussion, which follows our decision making. The opening has been filmed in the same way, to provide additional documentation. Not all the material we produced is being used.

Reflection:

This project encountered us with the complexity and broadness of the issue we were referring to. It was a challenge for us to re-direct our project in a more focused and at the same time open ended way. We wanted to make a simple and suggestive gesture that enclosed important and complex content. The writing of the manifesto made us question our role as ‘formenters’ of ‘togetherness’ and our own collective opinions about politics. We had to choose between formulating our manifesto in a very simple and ironic way or in a very elaborated and explicitly critical way. This was a complicated decision to make and encountered us with the weight of language, questioning very closely the use we gave to it, because we often found it problematic. The end result was satisfying in the way that we could condense our ideas into a simple and powerful gesture.

Our involvement in project was not completely pragmatic but rather quite emotional, as we all find the core question a very imperative one, an important issue that should be dealt with respect and thought. As the dynamic between the group gathered some tension, for unrelated reasons, we experience the instance of separation first hand – we observed the irony of us facilitating togetherness. Regardless of this minor tension we succeeded at finalising the work.

Other Readings

Eating Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Food, Tobias Döring, Markus Heide, Susanne Muehleisen, 2003 Food Is Culture, Massimo Montanari, Columbia University Press. A Companion to the Anthropology of Europe By Ullrich Kockel, John Wiley & Sons, 2015 Clash of Civilisations, Samuel P. Huntingdon Design as Art, Bruno Munari, Penguin Adult, 2008