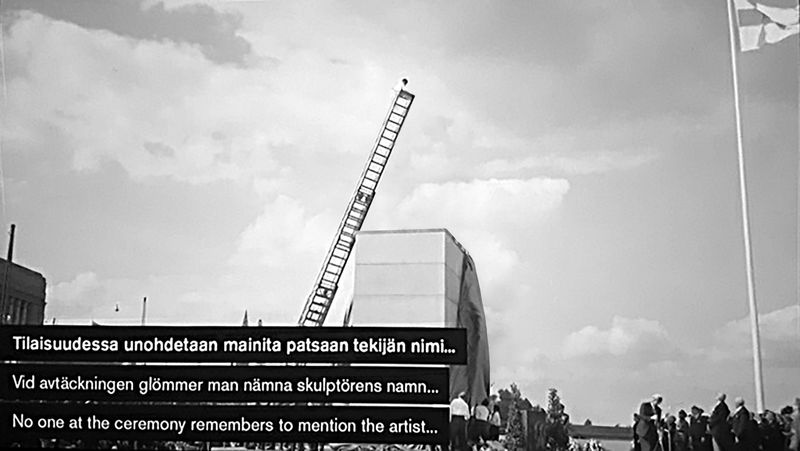

No one at the ceremony remembers to mention the artist

Essay for Vidha Saumya’s exhibition 'No one at the ceremony remembers to mention the artist', Third Space, 2015

In her current body of work, Vidha Saumya questions through history and theories of present times, the importance, placement and relevance of what have come to be established as icons of ‘nation’ and perceived culture. On view are 30 photographs, made using existing photographs and an instructional template process invented by her called ‘how to make a monument disappear’; and a companion series of 7 photographs called ‘becoming Mannerheim’. Each include the same basic elements – the Mannerheim statue missing from the plinth in the background suggesting a disjointed context, where individuals, ceremonies or other activities start seeming meaningless.

This process begins, with a stark and sudden undoing of the built up ideas around the Mannerheim image. Instead of slowly erasing it from memory, Vidha takes the proverbial axe and chops/ severs the image with a sudden blow. By removing the primary object/subject of the original photograph – the Mannerheim Equestrian statue, Vidha nulls the intention of the original image, putting it in a kind of existential crisis – here we as viewers must supplement it with a new meaning, a secular, more cosmopolitan meaning. We start looking at the secondary protagonists of the image – the tourist, the students, the bicycle group, the procession, the ceremony – all intending a certain relationship with the monument. We see them now independent of the monument’s shadowy grasp.

“…This questioning of history, national identity, patriotism, masculine ideas of heroic values started unraveling what I took for granted as an accepted history. I was thinking about artistic interventions through mediums of iconoclasm, argument, research and update to follow up on these questions.”

Through her work, Vidha enables a few questions of my own.

In this post information age where we have moved past the era of adoration, how do we as citizens of an increasingly global village, respond to the overarching presence of monumentalism? How do we stand to let remain the memorialisation of some of the more darker periods of our pan civilisational history? Can there be a monument of celebrating something that doesn’t exist? How long does it take for a monument celebrating a certain ideology to transform itself in the eyes of others to a tomb of itself? How can we as living beings learn to step out of the shadows cast by those represented, and create our own identity?

‘A general history about the Marshall and the statue explains that Baron Carl Gustav Emil Mannerheim (1867-1951) was the Marshal of Finland, Protector (1918-19) and President of the Republic (1944-46). The idea of a statue of Mannerheim riding his horse was proposed already in the 1930s but the first attempts to realise the proposal never succeeded. The idea resurfaced after Mannerheim’s death, and in 1952 a competition was arranged to find a sculptor. The first stage of the competition was completed in 1954. Following two further stages, the memorial statue was commissioned to the artist Aimo Tukiainen.

The unveiling of the statue took place on June 4, 1960 […]’*

In her quintessential brand of satirical humour, Vidha has named the exhibition, ‘No one at the ceremony rememberes to mention the artist ’, a caption/history trivia during the unveiling of the Equestrian statue, where, you guessed it – No one at the ceremony remembered to mention the artist.

It points to the roles we choose to see for ourselves, to be that of the artist – the creator, the thinker, the doer, an agent or agency, as the situation demands; or the monument – an idealised objectification of societal aspirations and norms.

Let’s look at the physical construct of a monument. It is a larger-than-life scale, operating not on the level of history, but mythologising the subject. It forces us to look at it, not with critical eyes, but through the eyes of sentiment and emotion. And this emotion can be strong and can swing either way, but what we often lose under the gaze of monuments is the will to question. Vidha, by the process driven nature embedded within the work, re-informs of this will, and goads it into re-activation.

Ali Akbar Mehta

Helsinki

2016