Museum of Impossible Forms

- Museum of Impossible Forms

- Generating (An)Other Economy: Working Together at the Museum of Impossible Forms

- How to Work Together? Seeking Models of Solidarity and Alliance

- Museum of Impossible Forms: Voicing the Margins

- Cultural production and racism: How to challenge racist structures

- The Shape of Museums to Come

- SAFE{R}: Evolving the Conditions for Collaboration

- Who is Welcome? – Thinking Hospitality as Museum of Impossible Forms

- Notes for Radical Diversity

- CreaTures: Panel Discussion on Creative Practices for Transformational Futures

- Resistance and Reimagining Alternatives

- Atlas of Lost Beliefs (for Insurgents, Citizens, & Untitled Bodies)

- How to be a hospitable without being a motel: Thinking Hospitalities

- Re-Musing the Museum: Part II

- Locating: The Museum of Impossible Forms

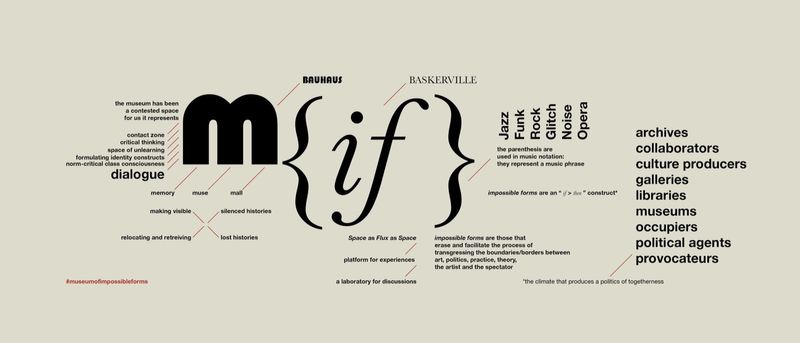

The Museum of Impossible Forms M{if} is an anti-racist, queer feminist cultural centre located in Sompassaari (originally Kontula). M{if} is built on the proposal that the ‘Museum’ is a space in flux – a contested space representing a contact zone, a space of unlearning, formulating identity constructs, norm-critical consciousness and critical thinking, already containing within it the potential for the para museum, the counter museum, the anti museum. ‘Impossible Forms’ are those that facilitate the process of transgressing the boundaries/borders between art, politics, practice, theory, the artist and the spectator.

As one of its founding members, I was appointed its Co-Artistic Director, form Aug 2018 - Dec 2020. During this time, my curatorial framework, The Atlas of Lost Beliefs: For Insurgents, Citizens, & Untitled Bodies, focused on collaborative, transdisciplinary, and intersectional community-building.

As the co-Artistic Director, I managed the library/archive, event logistics, daily operations, and finances. I conceptualised, coordinated production, and led teams of project leaders and curators to execute 160+ events, under a portfolio of designed and curated projects :

MIF Discourse Series

Society of Cinema, curated by Danai Anagnostou (2018-2019)

Performance LAB, curated by varialambo (2020) and Vishnu Vardhani Rajan (2018-19)

Improv Sessions, curated by Sergio Castrillón (2018-2020)

Radical Cross-stitch Workshops, hosted by Marianne Savallampi and Vidha Saumya (2020)

M{if} Monthly Dinners, hosted by Vidha Saumya and Ali Akbar Mehta

Feminist Anti-Rascist (FAR) Night School, curated by Arvind Ramachandran

Reading Circle

Entry to Iraniain Music, curated by Aman Askerazid

Summer School, curated by Christopher Wessels and Ahmed Al-Nawas (2017)

Impossible Reader, curated by Ali Akbar Mehta and Marianne Savallampi (2020) and Christopher Wessels and Sergio *Castrillón (*2017)

Special Events + Hosted events

- Ubuntu Film Club, curated by Alice Mutoni, Fiona Musanga, and Rewina Teklai

- Rehearsing Hospitalities (as collaborative partner of Frame Contemporary Art Finland), curated by Jussi Koitela and Yvonne Billimore

- POC Open Mic Nights, curated by Arvind Ramachandran,

Under these projects, we worked with 500+ artists, collectives, and institutional partners (per year) in various capacities, and attracted over 5600 visitors in 2019 and 2020.

I regularly wrote and lectured on M{if} and its decolonial, queer-feminist, and norm-critical ethos in multiple academic journals and publications, such as Marginaaleista museoihin, Rasismi, valta ja vastarinta, The Museum of the Future: 43 New Contributions to the Discussion about the Future of the Museum, Six years in the Third Space, Rehearsing Hospitalities Companion 1, and Rehearsing Hospitalities Companion 2; and at Conferences and talks, such as Notes for Radical Diversity at Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), Resistance and Reimagining Alternatives at the Center for Research on Ethnic Relations and Nationalism, (CEREN), University of Helsinki, Creative Practices for Transformational Futures at Aalto University, and Re-Musing the Museum: Part II at the Kiasma Contemporary art Museum.

Through these efforts, the Museum of Impossible Forms has been the recipient of the State Art Prize awarded by the Ministry of Art and Culture (2020) and the Tutkijaliitto-palkinto by the Finnish Association of Researchers (2019).

In short, the co-Artistic Directorship is a position of work that cuts through multiple strata of infrastructural praxis, and as such, is a consolidated set of roles that normally (within an institutional setting) would be distributed through a hierarchical framework. Through multi-layered, recurrent work, we have aimed to create a space and ethos that facilitates the conditions for making significant interventions through cinema, performance, music, spoken word, visual arts, and activism-based practices, discourses, and pedagogies.

Below are some of the theorisations and curatorial work done under the auspices of M{if}

Generating (An)Other Economy: Working Together at the Museum of Impossible Forms

in 'How to work together?', Impossible Reader 2020, (pub.) Museum of Impossible Forms

“[…]how to bypass the conditions of competition that are structured around the seemingly independent sea of art and cultural workers? This question is particularly pertinent in the context of Finland, where globally preferred methodologies of a white cube ‘gallery-collector-auction house’ method no longer find their ground, where the apparent focus is placed squarely on artists not having to sell artworks to survive, where instead practitioners may commit to the ‘important, critical, or otherwise exploratory methods’ of art-making, presumably outside the parameters of finance and economies.”

Citation:

Mehta, A. A. (2021b). Generating (an)other economy: Working together at Museum of Impossible Forms. In E. Aiava & R. Aiava (Eds.), How to Work Together: Seeking models of solidarity and alliance (pp. 149–176). Museum of Impossible Forms.

How to Work Together? Seeking Models of Solidarity and Alliance

Impossible Reader 2020, edited by Emily and Raine Aiava, conceived and produced by Ali akbar Mehta and Marianne Savallampi, for Museum of Impossible Forms, Helsinki FI

The Impossible Reader is a biennial book series published by the Museum of Impossible Forms. The theme of the 2020 reader is How to Work Together – Seeking models of solidarity and alliance. It gathers a selection of essays, writings and poems on and around the topic of collective working practices. The publication also reflects and celebrates the past four years of operations of the Museum of Impossible Forms cultural centre in Kontula.

Publication concept and Production*: Ali Akbar Mehta & Marianne Savallampi*

Edited by: Emily Aiava & Raine Aiava

Publication coordinator & graphic design: Zahrah Ehsan

published by Museum of Impossible Forms, Helsinki, FI.

ISBN (print): 978-952-94-4840-1

ISBM (pdf): 978-952-94-4841-8

download a free PDF from the Museum of Impossible Forms website here

The Reader features entries by:

Abdullah Qureshi

Ali Akbar Mehta

Arvind Ramachandran and Ella Alin

Egle Oddo

Feminist Culture House

Flis Holland

Jaakko Pallasvuo

Leonardo Custodio

Linnea Saarits

Marianne Savallampi

Nora Sternfeld

Pedra Costa

Raine Aiava

Renuka Rajiv

Saara Mahbouba

Sasa Nemec

Shia Conlon

Vidha Saumya and Sonja Lindfors

Yvonne Billimore and Jussi Koitela

Zahrah Ehsan

The Reader is available for purchase at the Museum of Impossible Forms.

Curatorial note:

Many of us, whether separately or collectively, have confided, shared or spoken out, about the difficult and precarious conditions in which most of us as artists and cultural workers continue to work. Most often our working conditions are exacerbated rather than relieved by the conditions of competition that frames the ecology of our art and cultural fields, whether competitions of resources, attention, spaces to exhibit, or grants. These conditions of competition exists across visual, literary, music and sound, cinematic, conceptual/ contemporary and other forms of arts, as well as within social, political and activism based workings; and in many ways ties us together as fellow-competitors, despite our collective wish to work together as friends, collaborators, and like-minded individuals.

We at Museum of Impossible Forms aim to take these conversations forward and consolidate our thoughts into a singular form, without hopefully losing the plurality of the voices that need to speak about the unsustainable nature of this ecology and strain it puts us in our various spaces of thinking, making, doing, and producing.

In our work since 2019 and guided by our curatorial framework, An Atlas of Lost Beliefs: For Insurgents, Citizens, and Untitled Bodies, the Museum of Impossible Forms have laid primary emphasis on collaborative working, either in sharing resources or simply offering the M{if} space. In 2019, approximately 35% of the events conducted were such collaborations or simply events that we hosted. Placing ourselves under these conditions not only allowed us to learn more, but it also allowed us to learn more diversely. It created for us the conditions to create a new series of ongoing events in directions we could not have anticipated. The Museum led us in directions of knowledges we didn’t know we needed to ask.

Museum of Impossible Forms initiates the second volume of its Impossible Reader under this rubric, titled HOW TO WORK: Seeking models of solidarity and working In alliance.

- Ali Akbar Mehta

.

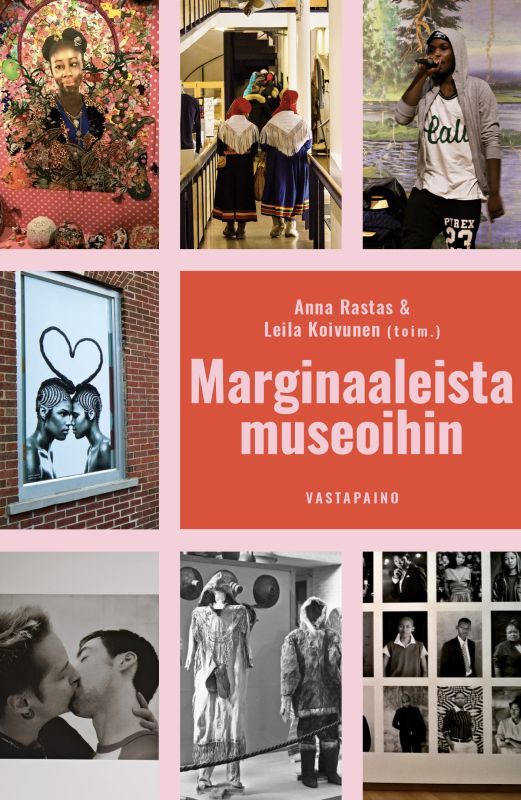

Museum of Impossible Forms: Voicing the Margins

in 'Marginaaleista museoihin'. (From Margins to Museums), (eds.) Rastas, Anna & Koivunen, Leila, (trans.) Nurmenniemi, Jenni, Tampere: Vastapaino, FI

What constitutes the Margins? And how do we calculate with any precise method the marginality of any lived experience?

“The margins cannot be understood as a linear or spatial distance from a location that is assigned as being the ‘center’. For instance, geographically speaking, suburbs are margins vis. downtown areas, downtown areas are margins vis. the city center, gated communities enjoy aspirational value and become centers of posh living, and ghettos and slum areas become abject spaces, supermarkets and malls become centers of commerce, while an arcade-style mall like the one where the Museum of Impossible Forms is located has become relegated to curios of a past that governments and bureaucracies wish to redevelop. If the center-margins relationship is a cascading series of hierarchies rather than an absolute binary, where any location’s marginality is contingent upon another, perceivably more central location, then the relationship is not only spatially and temporally configured as a passive ‘being in’ the margins, but an actives process of marginalization. It must be re-conceived as a complex network of power relations, across lines of system infrastructures, data protocols, architectures of control and structural discriminations, of individual and collective bodies themselves in flux.”

The article is published in ‘Marginaaleista museoihin’. (From Margins to Museums), (eds.) Rastas, Anna & Koivunen, Leila. (trans.) Nurmenniemi, Ki. Tampere: Vastapaino, FI

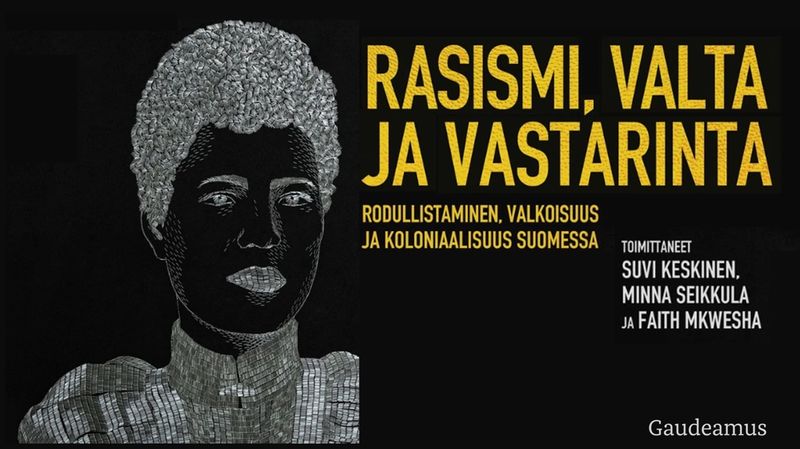

Cultural production and racism: How to challenge racist structures

in 'Rasismi, valta ja vastarinta' (Racism, power and resistance), (ed) Suvi Keskinen, (pub.) Gaudeamus

Essay written in collaboration with Marianne Savallampi, for Racism, Power and Resistance (in Finnish)

Everyday racism is often subtle and not appalling. Many don’t even understand their behavior as racist.

Racism permeates Finnish society as an everyday and experiential phenomenon, but it is also an institutional and structural problem. The Black Lives Matter movement has also sparked a debate here and shown that many people need information that is specifically adapted to the Finnish environment and based on research. Who can or must talk about racism?

Racism, power and resistance present racism and colonialism in Finnish society and their global connections. Everyday examples of high school TET training for policing are eye-opening. The work questions the racist definitions of Finnishness and the unhistorical understanding of racism, and makes anti-racism visible. The work gives voice to racist researchers and civic activists and provides tools for anti-racist action.

citation reference:

Savallampi, M., & Mehta, A. A. (2021). Museum of Impossible Forms ja antirasistisen kulttuurituatannon haasteet. In S. Keskinen, M. Seikkula, & F. Mkwesha (Eds.), Rasismi, Valta ja Vastarinta (pp. 221–224). Gaudeamus.

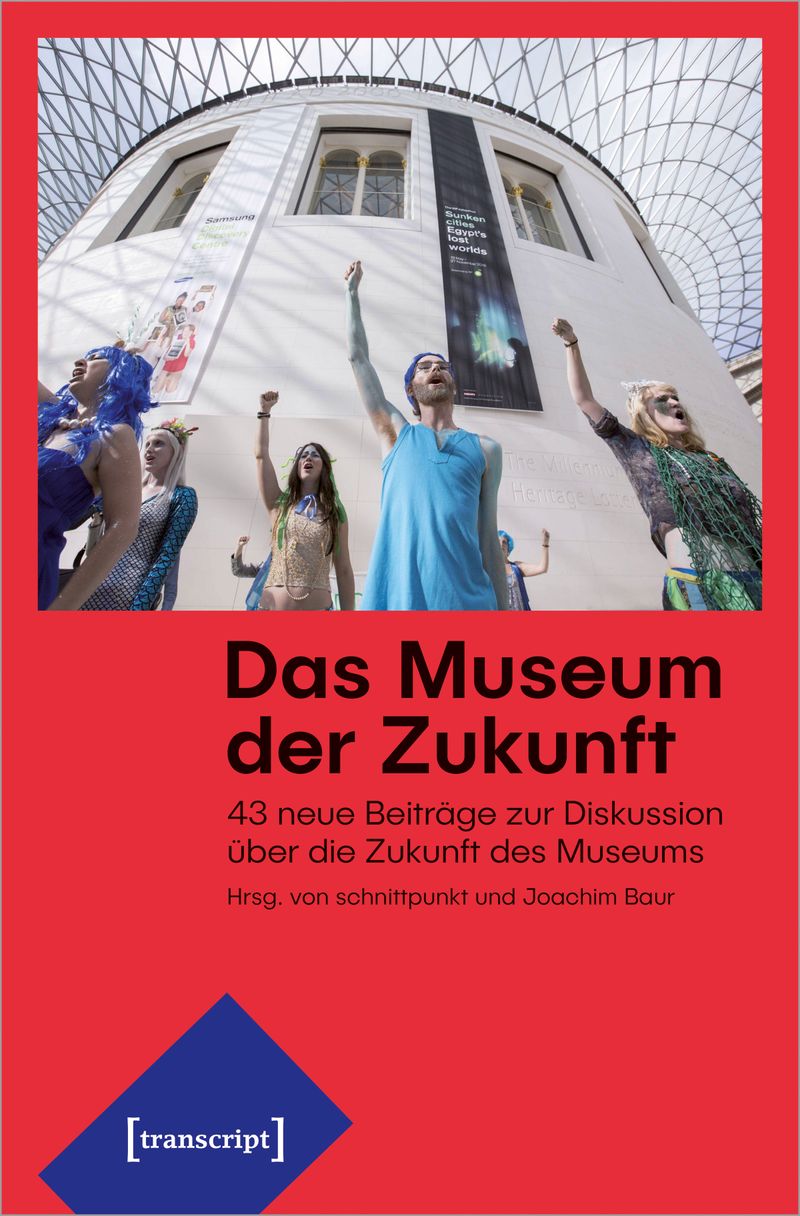

The Shape of Museums to Come

in 'The Museum of the Future. 43 New Contributions to the Discussion about the Future of the Museum', (ed.) Nora Sternfeld, (pub.) schnittpunkt and Joachim Baur

“The 19th-century museum is dead.” But the ghosts, ghouls, undead spectres of the old museum still haunt us, hovering over the boulevards of contemporary imagination and the bylanes of our futurity. Such museums, remnants of another time and place, are extensions of a colonial gaze preoccupied with the centralisation of power, and physical proofs of its own labour to ‘bring’ culture as enforced methods of living to the far-off, distant and exotic margins of the Eastern and the Western, the Northern and the Southern corners – in as much as there can be corners on a round ball of stone, mud, and water; as well as a method to ‘take’ objects that were less of a curiosity and more trophies of power. Historical objects in museums are more often than not contested objects; whose cultural significance is either questionable to begin with, reflecting a colonial, classist, misogynistic, or otherwise xenophobic relationship to the world of its time; or a hegemonic relationship between the museums and countries currently housing or ‘owning’ them, and their countries of origin; or objects that in their own relative status of uniqueness have now ossified into an oblivion of permanence.

-excerpt from text

“The Museum of the Future was published in 1970. 43 contributions to the discussion about the future of the museum. 50 years later, a publication brings together 43 new contributions by international authors from museum practice, from theory, education, art and architecture. They create concrete visions of a museum of the future: confident and doubtful, critical, clearly positioned and subjective. What do visions of the future accomplish and what do they make impossible? How empowering or disempowering are speculations about the future for a change in the museum of the present?”

For more information on the publication and to download the editors’ introduction, please see here.

SAFE{R}: Evolving the Conditions for Collaboration

in 'Six years in the Third Space', Third Space, Helsinki (published online)

"The word collaborate comes from Latin roots. Words beginning with the prefix ‘col-’ meaning together, implying doing something together. The root word ‘laborare’, also from Latin, gives us many of the English words used to talk about careers and work. In fact, the word labor comes from this root word. Putting the two Latin parts of this word together, the word literally means ‘to work together’.

Today, Collaboration is at the core of any artistic, curatorial, choreographic, literary, or activist work, fundamentally transforming the ways in which we think of each of these fields of work both individually as well as collectively. Not even museum thinking, or thinking about museums as a form of critical artistic praxis can happen in isolation, and perhaps it is important to clarify that I write this not as an individual, but as a representative of a collective, a cultural center, a para-institution called ‘Museum of Impossible Forms’ (M{if}). Formed in 2017 and located in Kontula Helsinki, M{if} was borne out of a need for art and cultural spaces for artists and communities located in the margins. Now in its fourth year of working, it has metamorphosed into an indispensable resource within the multiple artistic, curatorial, activist, and pedagogical discourses in Helsinki, Finland, and the Nordic region; and continues to make its presence felt as a decolonial, antiracist and queer-feminist project. As a heterogeneous space of unlearning, it has fostered experimental migrant forms of expression, norm-critical consciousness, and critical thinking through extensive programming towards building multiple vibrant communities within the tessellated folds of its space.

…

In 2020 Third Space celebrates its 6th anniversary with an interdisciplinary program revolving around the complex theme of COLLABORATION. Access the online publication and the full text here.

Read more about Third Space here.

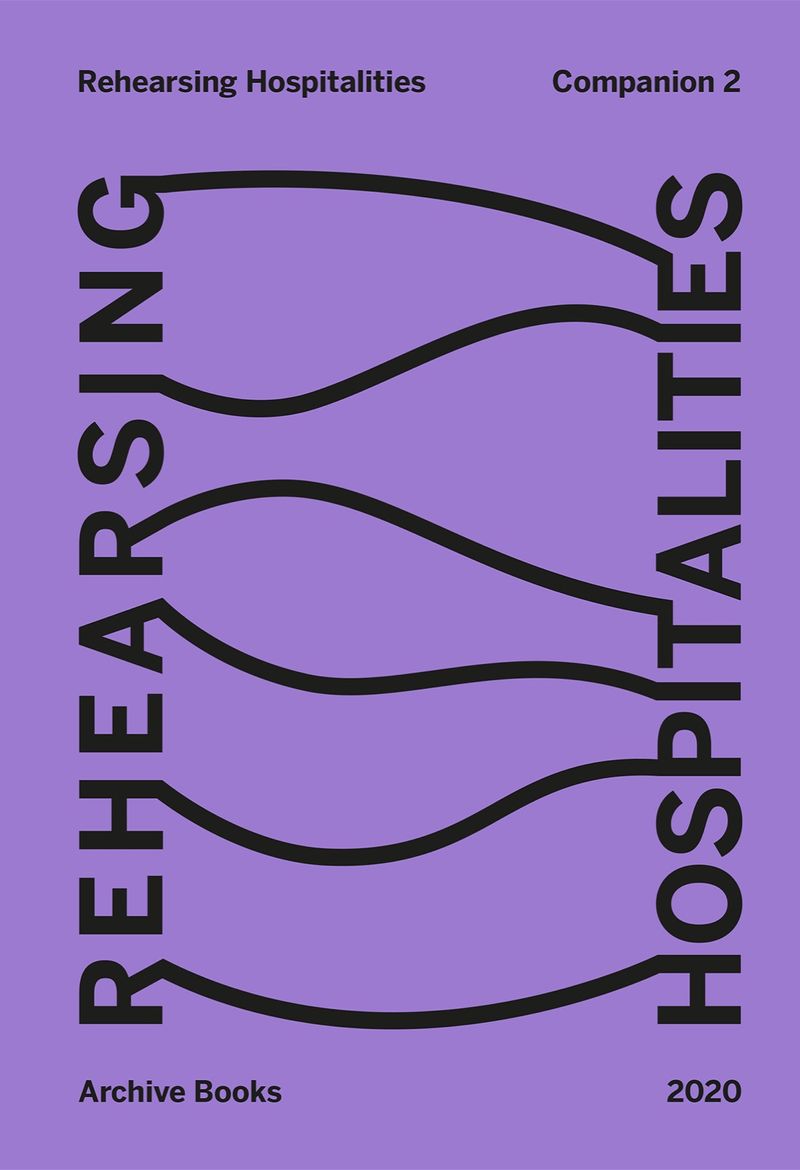

Who is Welcome? – Thinking Hospitality as Museum of Impossible Forms

Rehearsing Hospitalities Companion 2, (ed.) Yvonne Billimore and Jussi Koitela, (pub.) Archive Books, Berlin, in collaboration with Frame Contemporary Art Finland, Helsinki, FI

“…the issues of hospitality and fantasy are inextricably linked – the promise of equality has always been weighed against its counter mechanisms of right-wing populist politics, neoliberal capitalism, ethno-fanato-nationalism, and its older more virulent strains of memetic concepts, namely patriarchy, misogyny, cissexism and its pseudo-scientific offspring – race, class, and caste. A relationship between reason and unreason (fantasy) embedded within the late modern criticism has been the basis of articulation for a certain idea of the political, the community, the subject – a ‘Biopolitical’ agency, one that inherently above all and everything else is ‘able to’…”

Buy the publication or download the free PDF on Archive Book’s website here

Notes for Radical Diversity

Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), Helsinki

In November 2019, I was invited to talk about diversity within the art and cultural scene of Helsinki, to the curatorial staff at Helsinki Art Museum, Helsinki.

The following is the prepared text of the talk and workshop:

Thank you for inviting me to talk about Diversity.

Although this term and its implied meaning are far-reaching into my own work and practice, there are essentially three positions that I can take:

One, a position that comes embedded into the nature of my own research-based practice as an artist, where I create participatory archives and archive-based projects to examine collective histories of memory and identity within the framework of violence, conflict, & trauma.

Two, my work as one of two Artistic Directors of Museum of Impossible Forms, and the nature of the work we do as a cultural space in Kontula, forming and sustaining micro-communities around decoloniality, postcoloniality, intersectional feminism, queer theory and norm-criticality – through regular and ongoing projects.

Three, as a doctoral student at Aalto University working towards generating a conception of Performativity within the contexts of online spaces and once awareness is generated of the reciprocal relationship between us and the archives we create, to use that awareness to create politically conscious future archives – which again feeds into my practice.

Now that this, my short introduction is done, my speculations about ‘Diversity’ as a term will interweave these varied roles as Artist, artistic Director, and Doctoral researcher.

I always think it’s good to think about how you arrive at the work that you do. There’s always a story to the combinations that we bring to our work and to the world. And I would like to thank the Helsinki Art Museum for inviting me to share my notes on Diversity and to acknowledge that you are involved in creating a cultural vibrancy in Helsinki and Finland, and to thank you all for being a part of this effort.

Stepping back to square one, “What is Diversity?” – Is it a collection of different or diverse objects, things, or people? Is our conversation about these, objects, things, and /or people in of itself, without context? If not, what are the contexts through which we must view the term diversity?

Exercise 1:

Make a group of 4 persons per group and ask them to identify 1 thing that connects them to each other, and 1 thing that sets them apart.

(similarity) and (difference)

Diversity is the collective negotiation of our differences and similarities.

Write down at least 3 types of formulations of Diversity that you are aware of – for example, Gender diversifies the human and non-human subject into male, female, genderqueer etc.

Going back to your groups of 4, discuss why they are a legitimate form of diversity exemplifying your situation or your situatedness.

Discuss as a whole group.

Diversity vs. Critical Diversity: A History

The term diversity is usually traced back to the mid-1980s, when demographic projections in the Workforce 2000 Report published by the Hudson Institute showed that by the year 2000 the US labour force would become more heterogeneous, with new entrants comprising significantly greater numbers of women, racial minorities and immigrants than ‘native’ white men. The report urged policymakers and organizations to address this growing diversity if the US was to maintain its economic dominance in the 21st century. The notion of diversity revolutionized the understanding of differences in organizations, as it portrayed them for the first time in the history of management as strategic assets, which if well managed, could provide a competitive advantage. From a resource-based view of the firm, diversity was conceptualized as a set of rare, valuable and difficult to imitate resources. Companies properly managing diversity would attract and retain skilled workers in an increasingly diverse labour market, better service increasingly diverse markets by matching diverse customers with a more diverse workforce, improve organizational learning and creativity through employees’ exposure to a wider range of perspectives, and increase organizational flexibility in increasingly turbulent contexts. Such understanding opened the way to including, next to gender and race/ ethnicity, a broader variety of identities that could potentially contribute to the bottom line, such as age, sexual orientation, disability, obesity and even functional background, personality, attitudes and value orientation. Diversity served as an umbrella concept under which any individual characteristic could be subsumed, diminishing the risk of inter-group conflict between the majority and minorities.

The business rationale at the core of diversity has often been used to explain the popularity of this notion within the US business world and later, its diffusion to other western countries. The business rationale also informed much of the academic research on diversity, which focused on understanding the effects of a variety of identities on groups’ processes and outcomes. Developing such understanding was considered both by academics and practitioners as the necessary first step to proper diversity management.

For instance, Cox and colleagues (1991) studied the effect of ethnic composition on cooperative and competitive behaviour in groups, while Jehn and colleagues examined how group’s informational diversity (education and experience), gender, ethnicity, age and diversity values (differences in perception of the groups’ real task, goal, target omission) affected both group performance and workers’ morale and commitment (1999).

Critical Diversity

Whereas research on Critical diversity is relatively recent, studies of the position of specific socio-demographic groups in organizations date back to the 1970s. Preoccupied to show that organizations are not the meritocracies we like to believe they are, scholars documented how inequality in organizations was structured along with gender and racio-ethnic lines and investigated the underlying mechanisms that produced it. Within the gender literature, a few women scholars investigated the social mechanisms marginalizing women in the workplace. Through organizational ethnography, Rosabeth Moss Kanter showed how gendered roles, relative numbers, network structures and sex-specific reward systems kept women in subordinate professional positions. Cynthia Cockburn analysed how key technical competencies were constructed as masculine to exclude women from new professions emerging from technological innovation. Ruth Cavendish examined how class, gender and imperialism shaped the gendered division of labour, while Aihwa Ong examined how modernization has affected the lives of Malay women and how they resisted oppression in the new economy. These few significant works contributed to the emergence of the vast literature on gender in organizations that examines the complexity of gender in organizations from a wide variety of theoretical approaches. In the field of race studies, some early pieces called attention to the silencing of race as an organizational phenomenon and how race operated as an organizing principle. Alderfer and colleagues (1980) approached race relations in organizations as a multi-level issue of power differences in groups, organizations and societies. Omi and Winant (1986) showed how an ethnicity-based paradigm that emphasized the nature of ethnic identity and the impact of ethnicity on life experiences influenced theories on race in organizations to the point that the core question centred on the lack of assimilation of ethnic minorities in the workplace.

Whereas these early studies drew from a sociological paradigm to better understand how gender and race/ethnicity operated as principles of organizing, later ones mostly drew on a social psychological paradigm to understand the specific constraints faced by women and ethnic/racial minorities in the workplace. Typically, scholars investigated the impact of race/ethnicity or sex on artwork and career-related outcomes such as access to mentoring and networks, satisfaction, performance evaluations, promotion opportunities and income. They found extensive evidence of unequal treatment of female and black/ethnic minority employees, with negative effects on their work satisfaction and careers. These unfavourable outcomes were generally explained in psychological terms, as the effect of prejudice and discrimination. For instance, social identity theories explain discriminating behaviour as resulting from the need of human beings to classify themselves and others into groups to reduce the complexity of the social world and better anticipate social behaviour. Such classifications are commonly based on traits such as skin colour and sex, which are readily available to perception. Prejudice and bias arise from ethnocentrism – human beings’ need to evaluate their own group more positively than other groups in order to build a positive self-identity. Other social psychological theories such as homophily and the similarity-attraction paradigm rather explain discriminatory behaviour by positing that individuals tend to interact more frequently and to like others who are similar to them.

This later research has, till today, played an important role in documenting persistent inequality along the lines of gender and racio-ethnicity in the workplace. Through hard data, it makes visible the ‘inconvenient truth’ of unfairness and discrimination causing vertical segregation and the glass ceiling. Yet, the predominance of social psychological approaches has also resulted in a narrow understanding of the processes leading to inequality, namely, one that largely overlooks structural, context-specific elements.

Exercise 02

15 minutes

What are the forms of Diversity (Critical or otherwise) are you in contact with, either personally at home or in your social circles, professionally through your work, at the Museum, In Finland or the World in general?

Critical diversity can be defined as the equal inclusion of people from varied backgrounds on a parity basis throughout all ranks and divisions of the organization. It especially refers to the inclusion of those who are considered to be different from traditional members because of exclusionary practices.

Within cultural spaces in Helsinki, the question of diversity means equivalent inclusion within institutions and organisations such as universities, museums, galleries and unions, of members of different genders, ethnicities, nationalities, and cultural backgrounds – to adequately represent the society that these organisations aim to represent.

Diversity is embedded within other discourses, and cannot be studied in isolation understood without proper inquiries into other fields of knowledge, primarily:

- Diversity of Identity

- Diversity of Gender and Sexual orientations

- Diversity of Racial / Ethnic Minorities Discriminations

- Diversity of Power relations, and the recognition of privilege, oppression, and Hegemony

- Diversity of Intersectionality within Feminism

- Diversity of Radicalised, Marginalised and Other Bodies / Communities

- Diversity as Transnational multiculturalism

Exercise 03:

15 minutes

What do you think is the role of the Museum?

What do you think is the role of the Museum in creating a responsible representation of these diversities that you are familiar with?

What does Critical Diversity as a field of practice do?

Critical diversity literature has developed on the ground of three fundamental points of critique towards the diversity literature and, specifically, the social psychology theories on which it relies.

First, a number of scholars have pointed to the problems deriving from a positivistic ontology of identity underlying these studies. Identities are conceptualized as ready-made, fixed, clear-cut, easily measurable categories, ready to be operationalised as the independent variable to explain the specific phenomenon under study. Such an unproblematic approach naturalizes identities into objective entities, rather than acknowledging their socially constructed nature. It reduces individuals to representatives of a social group distinguished by a common socio-demographic trait, the repository of 'true’, essential identity. Furthermore, it has been argued that comparisons are not made between groups, but by taking white, heterosexual, western, middle/upper class, abled men as the term of reference, and measuring other groups’ difference from this norm. Despite the ambiguity of the term ‘diverse’, which refers to the heterogeneity in a group, in the comparison, it is actually the other that becomes the object of study and that is discursively constituted as marginal, from the vantage point of a dominant identity.

Second, social psychological approaches have often been criticized for their tendency to downplay the role of organizational and societal contexts in shaping the meaning of diversity. In some cases, studies have examined how specific contextual elements, such as the type of task, task interdependence, time, and diversity perspectives moderate the relation between diversity and group outcomes such as performance or cooperation and conflict. However, the assumption remains that identities are predefined and the focus is rather on which identity becomes salient in the categorization process, neglecting the role of context in shaping the meaning of identities itself.

Finally, a third related point of critique concerns the inadequate theorisation of power. The micro-lens of social psychology leads to an explanation of identity-based power inequality exclusively as the result of individual discriminatory acts originating in universal cognitive processes. Such acts remain disembedded from the greater context of historically determined, structurally unequal access to and distribution of resources between socio-demographic groups. The diversity literature goes even further than the literature on minorities in that it does not merely neglect power dynamics, but rather takes a clearly managerial perspective – and thus the perspective of the more powerful party in the employment relation – on differences. As the main aim is to better understand the working of diversity in order to manage it properly and leverage it for increased performance, differences are approached instrumentally, as a potential source of value that needs to be activated by virtue of the employment relationship.

Critical diversity has focused on addressing these concerns. A first group of studies analyses the discourses through which specific identities and diversity are constructed in distinct ways by actors in specific social, historical and, more rarely, organizational contexts. Either focusing the analysis on the textual aspects of discourse or linking discourse to the wider social context from which they emerge, these studies show that members of specific socio-demographic groups are defined in essentialist terms, as representatives of a specific socio-demographic group lacking fundamental work-related skills (or, more rarely, as having additional skills).

A growing body of literature investigates minorities’ active engagement with societal and/or organizational discourses of diversity in their own identity work, specifically attempting to construct positive, empowering professional identities. From a similar agent-centred perspective, others have examined how diversity practitioners constantly negotiate the meaning of diversity in their jobs, struggling to balance the business case and equality rationales in order to be heard by key stakeholders, effectively advance equality, and maintain a meaningful professional identity. Together, these pieces show that discourses, while powerful, never fully determine identity. Individuals neither simply step into ‘prepackaged selves’, nor are mechanically put into them by others once and for all. Despite their subordinate positions, subjects continuously engage, as agents, in identity work to construct, maintain and/or disrupt (multiple) identities favourable to them, challenging inequalities.

Within the gender and ethnicity literature, the identity work of those in positions of power has also increasingly become the object of investigation. Men’s identity and masculinities are no longer unmarked within organizations. Analyses have shown how constructions of work and masculine identities mutually inform each other, conferring status, powers and authority on men in work contexts. As a result, men’s powers and authority, social practices and ways of being have been questioned and problematised. In similar logic, there is a growing interest in the notion of whiteness in organization studies. Scholarship on the formation of white identities, ideologies and cultural practices has been a project mainly driven by US scholars inspired by the pioneering work of DuBois(Nkomo, 2009; Twine and Gallager, 2008). In organization studies, two theoretical pieces on whiteness by Grimes (2001) and Nkomo (2009) draw attention to the need to interrogate whiteness and shed light on how whiteness informs both practices within the discipline of organization studies and the language and terminology white scholars commonly use. In an empirical study of how whiteness informed the professional struggles of the white South African Society of Medical Women, Walker (2005) examined the ways white women doctors could gain access to the medical profession during the apartheid thanks to their white race, showing the inextricable link of Race to gender identities and patriarchy.

Yet another promising approach to diversity in organizations draws on intersectionality studies. Today a burgeoning concept, intersectionality was originally developed in black feminist studies to understand the oppression of black women through the simultaneous and dynamic interaction of race and gender. Applied to organizations, intersectionality allows connecting multiple work identities to wider societal phenomena, leading to a more fine-grained analysis of the processes of identity construction and the underlying power relations. Although the importance of intersectionality is widely recognized, relatively few empirical studies have applied this concept to organizations.

Other critical scholars have re-proposed a critical sociological lens, theorizing how specific socio-demographic identities function as principles along which inequality is structured in organizations. For instance, Essed (1991) developed the concept of everyday racism that integrates the macro and micro dimensions of racism to account for the processes that incorporate racist notions into the daily practices of organizing. Nkomo (1992) noticed how Race could be developed as a productive analytical category when organizations are analysed as sites in which race relations interlock with gender and class relations played out in power struggles. Calás and Smircich (2006) and Alvesson and DueBilling (2009) discussed how gender shapes organizations and organizing, while Acker (2006) proposed the notion of ‘inequality regimes’ to conceptualize interlocking practices and processes that result in continuing inequalities in all work organizations.

Finally, some journal special issues and volumes have been dedicated to advancing our understanding of diversity and equality within highly heterogeneous demographic, historic, social, institutional and geopolitical contexts including examples of the specificity of diversity management and its very meaning and practice in several countries across the globe. Many have problematised and challenged the wholesale export of the US-centred conceptualization of diversity and diversity management to other countries. In an early piece, Jones and colleagues (2000) examined how a US ‘model of difference’ and diversity management did not apply in Aotearoa/New Zealand, a country lacking equal opportunity legislation comparable to that of the US and where the Maori have a specific status as indigenous people. Omanovic examined the re-interpretation of the notion of diversity within the Swedishsocio-historical context characterized by specific conflicting interests, while Risberg andSøderberg (2008) studied diversity management in the Danish cultural context, showing how it significantly differed from the US and British multicultural societies. Drawing from transnational, feminist anti-racism, Mirchandani and Butler (2006) proposed to go beyond the inclusion and equity opposition by reconceptualizing relations of gender, class and race within the ever-present context of globalization. Mir et al. (2006) called attention to the need for theoretical perspectives that examine individuals’ embeddedness in local racialized, class-based and gendered hierarchies within the broader process of the globalization of labour and capital.

Exercise 04:

15 minutes

How do you think that the Museum – as a cultural organisation and an institution for pedagogical change – creates an adequate responsible representation of these diversities? or who is the Museum targeted for?

Happy Diversity

In light of prevailing discourses on homogeneity and anxieties about cultural differences, the concept aims to emphasise the positive sides and inevitability of heterogeneity and the constant need of mutual adjustment and adaptation. The moral panic about immigration and ethnic diversity also inspired scholarly discourses that, conversely, celebrated the growing hybridity and diversification of cultures and identities. Recently, in Dutch-speaking Belgium and the Netherlands, anthropologist Steven Vertovec’s concept of “super-diversity” is also increasingly being employed by anti-racist civil society organisations and some of the more alternative media and grey literature. The prefix ‘super’ seeks to grasp the contemporary proliferation of new conjunctions and interactions due to globally expanding mobility, yet also the necessity of understanding ethnicity in conjunction with a range of other social variables and with social inequalities.

However, diversity has also become a highly fashionable concept, ranging from popular calls to protect biodiversity, to diversity management courses and special training schemes. Many organizations have campaigned for creating a new inclusive image, which includes the token woman or ethnic or racialised minority person. Diversity is turned into a commodity in advertising: think of the Benetton ‘two-tone’ marketing campaign which displayed beautiful, smiling people of a variety of ‘races’ in “a sort of pluralistic celebration at the global temple of consumption”. Diversity is widely seen as a positive quality and is increasingly being recognised as an important value in a variety of contexts and a goal for all sorts of institutions. Yet, we join more critical voices who warn that the ease of diversity’s adaptation in commercial, institutional and policy language may be a sign of the loss of its critical-emancipatory potential.

Although contemporary anthropological understandings of socio-cultural diversity are far more dynamic than some of its older and more recent essentialist conceptions one might find that in both ethnocentric and multiculturalist discourses today,in recent years, the “turn to diversity” has come under heavy criticism and it remains problematic in many respects. One of the dangers of diversity discourse or what Lentin and Titley call the “politics of diversity”, the “institutional and broadly managerial deployment of diversity as a dimension of integration governance”, is that both individuals and groups (most often minority groups), are reduced to their diversity, such as their culture, ethnicity or religion against an unmarked norm (such as white, western, secular, able-bodied…) that remains unquestioned and out of view. White normativity and implicit assimilationist assumptions in diversity discourse reduce minority groups to “add-ons” of the dominant culture, that can add flavour to a white centre.

Secondly, “good diversity”, or “happy diversity” talk, even among the most politically engaged individuals, may underplay or even mask the role of power and privilege. Feminist theorist Sara Ahmed, for example, in her study of the experiences of diversity practitioners in higher education, shows how there is a paradox between the official language of diversity and the experience of those who “embody” diversity (Ahmed, 2012). Racism may be obscured when diversity becomes institutionalised and is used as ‘evidence’ or the ‘solution’ to the problem of racism. Diversity is likely to become “a diversity without oppression,‘’ one that “conflates, confuses and obscures the deeper socio-structural roots and consequences of diversity”. Yet, it is not only the widespread colour-blind rhetoric and neglect of everyday racism that needs our attention (Essed, 1991). Uncritical postmodern celebrations of cultural hybridity and of immigrants as the cosmopolitan hybrids par excellence in some scholarly work have also been criticised for sidestepping profound global inequalities.

As Ahmed (2012) notes, feminists of colour have offered some of the most cogent critiques of the language of diversity, and there is a whole genealogy of inspiring anti-racist, postcolonial, decolonial and transnational feminist thought that can be drawn upon which would be impossible to summarise here. A gender-critical perspective, and more precisely, a feminist intersectional perspective has proved to be very useful in foregrounding the relationship between power and difference. Yet, Ahmed also warns against a one-sided “happy” understanding of intersectionality, she says:

We can ask: what recedes when diversity becomes a view? If diversity is a way of viewing or even picturing an institution, then it might allow only some things to come into view. Diversity is often used as a shorthand for inclusion, as the ‘happy point’ of intersectionality, a point where lines meet. When intersectionality becomes a ‘happy point’, the feminist colour of critique is obscured. All differences matter under this view. (Ahmed, 2012, p. 14)

Ahmed’s plea is therefore not to stop doing diversity, but question what we are doing with diversity. She pleads, for instance, for critical evaluation of institutional diversity measures as to their intention to structurally challenge the institutional whiteness of academia or to merely change perceptions of whiteness. Intersectionality can help to remain sensitive to the “actual power by which the diversity discourse is paradoxically structured and reproduced” as well as to the systematic inequalities and privileges that tend to be obscured by the current managerial focus on diversity. Critical whiteness studies and critical race studies have similarly contributed to the exposing of the privileged unmarked norm, as have disability studies, deafness studies, and earlier, LGBTIQ studies for other forms of so-called neutrality and privilege. These fields all emerged in the wake of the very first feminist critiques of the academy, its numbers, its knowledges and its institutions, and it is our hope we will see some of this emerging work taking place in the Dutch-speaking context of this journal soon. In conclusion, adding diversity to gender to us seems a good strategy, as is adding gender to diversity, if alone for reminding us of the importance of the intersectional critique of the relationship between difference and power.

Exercise 05:

20 minutes

Who is included in the Museum? or Who enters the Museum on a regular basis

Who is not included? or what diverse communities that exist in Helsinki do you not see enter the Museum?

Why?

What can be done to change this?

Why has it not been done before?

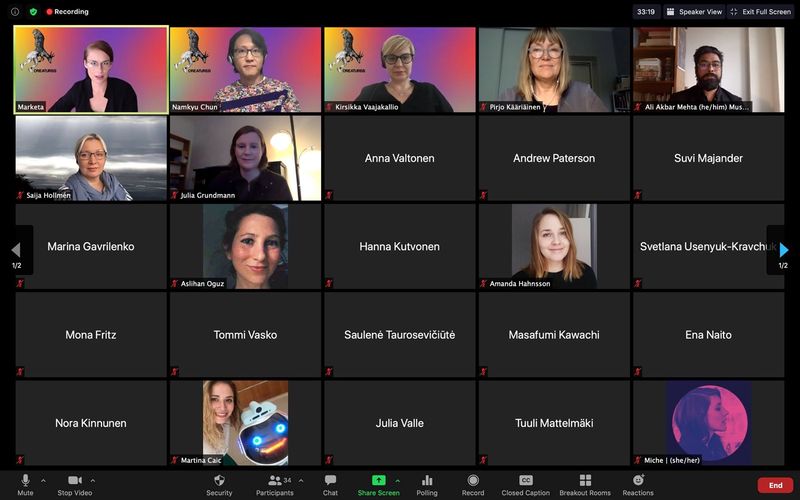

CreaTures: Panel Discussion on Creative Practices for Transformational Futures

Aalto University, Helsinki, FI (online)

Invited to speak about the Museum of Impossible Forms and its role as a transformative tool within the contemporary artistic and cultural scene of Helsinki, at Creative Practices for Transformational Futures Panel Discussion as part of Helsinki Design Week.

The CreaTures Panel Discussion at Helsinki Design Week will open a space for discussion about existing and potential roles of creative arts and design in driving socio-ecological transformations.

Moderated by Namkyu Chun and Marketa Dolejsova, the panel discussion was part of the introductory discussions as part of the The CreaTures project. The project is aimed to demonstrate the power of existing–yet often hidden–creative practices to move the world towards social and ecological sustainability through addressing ways of being and lifestyles.

Altogether, temporarily and throughout, we had 90 something participants to the online panel discussion event yesterday. Thanks all for Zooming in, posing questions, listening, and taking part. Hope this discussion continues meaningfully!

Resistance and Reimagining Alternatives

Nordic Decolonial Workshop (DENOR) 3rd exploratory workshop: Decoloniality, Politics & Social Change, organised and moderated by Amirah Salleh-Hoddin, Center for Research on Ethnic Relations and Nationalism, (CEREN), University of Helsinki, Helsinki

In November 2019, I was invited to speak about Museum of Impossible Forms.

The following is the transcript of the talk:

I always think it’s good to think about how you arrive at the work that you do. There’s always a story to the combinations that we bring to our work and to the world. And I would like to thank the Nordic Decolonial Workshop for inviting me to share some of the work we do at Museum of Impossible Forms.

Good afternoon,

My name is Ali Akbar Mehta. I am here today to speak in my capacity as one of the Artistic Directors of Museum of Impossible Forms, who along with Marianne Savallampi are involved in the core programming of the space. Together we curate the space, undertake the administrative duties, provide technical support, shift the furniture and make the coffee.

Museum of Impossible Forms (m{if}) is a cultural centre run by artists/ activists/ curators/ philosophers/ and is located in Kontula, East-Helsinki. For us the Museum is a space in flux – a contested space representing a contact zone, a space of unlearning, formulating identity constructs, norm-critical consciousness and critical thinking. ‘Impossible Forms’ are those that facilitate the process of transgressing the boundaries/borders between art, politics, practice, theory, the artist and the spectator.

Museum of Impossible Forms is a free space, which means that not only does it not charge artists a monetary fee to use the space, but also that we make available our resources ( a multilingual library, an ongoing archive, and a space for events and workshops) and expertise to artists we host, and to the surrounding community. All events in the space are free for the audience to attend. Furthermore, we compensate invited guests, artists, curators and speakers to support the integrity and ethics of cultural labor which is all too often underpaid, and underappreciated.

The Museum of Impossible Forms opens up a broad horizon though its political character, its accessibility and openness, its multilinguallibrary, an ongoingarchive, and through itsworkshops and events.It facilitates curated discursive art programs, with an opportunity for norm-critical dialogue framed within the discourse of decoloniality, intersectional feminism, and queer theory. These equally create a complexmind-space fuelledby these socio-political ideologies that are shared by the members of the m{if}, and that become visible through our various efforts. We are striving towards a para-institutional culture that focuses on ‘Alternate Pedagogy’.

Museum of Impossible Forms M{if} was founded by an independent group of Helsinki artists/curators/philosophers/activists/pedagogists in spring 2017 as an antiracist and queer-feminist project, a heterogeneous space exploring experimental and migrant form of expression. It is the coming together of a collective of people – artists, curators, pedagogues, philosophers and facilitators – art and cultural workers who believe in the need for this space. M{if} currently consists of:

- Marianne Savallampi

- Ahmed Al-Nawas

- Raine Aiava

- Vidha Saumya

- Vishnu Vardhani Rajan

- Heidi Hänninen

- Selina Väliheikki

- Sergio Castrillon

- Danai Anagnostou

- Hassan Blasim

- Christopher Wessels

- Christopher Thomas

- Zahrah Ehsan

- Soko Hwang

- Giovanna Esposito Yousif

- David Muoz

Beyond these individuals, Museum of Impossible Forms works with a number of collectives, organisations and institutions to create a lattice of shared concerns and practice solidarity. Some of these are:

- FAR Night School

- Nynnyt Collective

- Feminist Culture House

- Kontula Art School project

- Academy of Moving People and Images

- Pixelache Festival

- UrbanAPA

- Silent University, North

- RABRAB Press, and

- Ruskeat Tytot

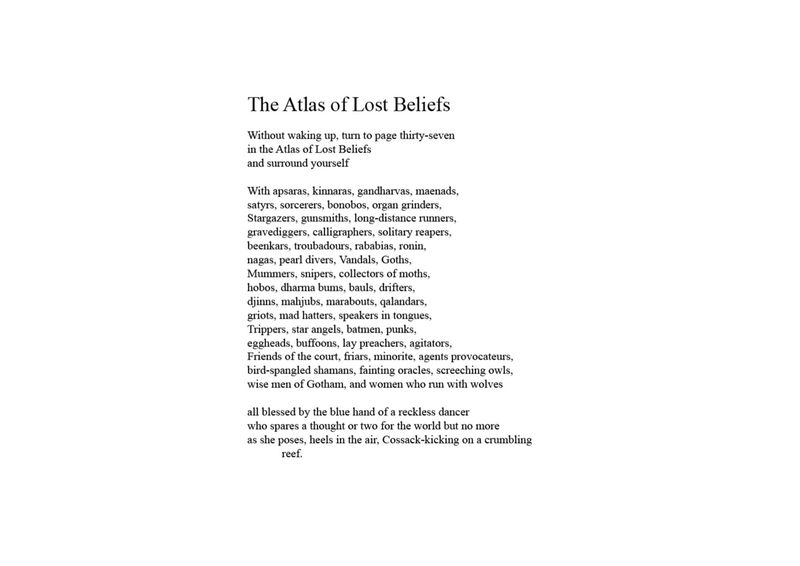

Our curatorial framework for this year has been ‘The Atlas of Lost Beliefs (For Insurgents, Citizens and Untitled Bodies)’, based on a poem by poet, cultural theorist and curator Ranjit Hoskote:

The Atlas is ‘a book of maps or charts’. We gazed into the Atlas and dreamt of places we would like to visit. The Atlas was our window to strange and alien worlds, connected by an incomprehensible amount of water. Today, the Atlas as a portal, as a device for dreaming is a forgotten artefact, instead mired in historiographies and anthro-political readings of a world that was.

Even now in a time obsessed with the past, devoted as it is to the cult of memory and the fetish of heritage, something still goes forward. Even now when there is no general direction, nor a subject who is supposed to lead, we cannot but ask where to place our next step, what to take along or leave behind. Yet there are still prospects, or in philosopher Bruno Latour’s words, “the shape of things to come.”

This future-forward projection of culture is enacted, in part, by Museum of Impossible Forms, because that is what we choose to do. Choice here is active participation.

In the poem, Atlas of Lost Beliefs, Ranjit Hoskote evokes an excerpt, a glimpse of a possible host of personas, both real and fictional, whom I can’t help but read as being ‘fellow insurgents, citizens, and untitled bodies’, all trying to swim in contaminated circumstances, to stay afloat in the infinite waters of precarity, seeking footing despite their groundlessness, subaltern characters not so very different from all of us – we are or have been each of them at some point in time, often all three, simultaneously, silently. And so we dedicate the coming year in solidarity with these, the cast of our collective narratives that connect the waters of our Atlas, who frame and address the engagement of cultural production with political and cultural predicaments in locations not ‘their own’ – whether described from a narrowly territorial point of view or within the contexts of secular, transnational, democratic, decolonial, queer, norm critical world(s); who allow us to ask, ‘What comes next?’

What can we learn from the Museum beyond what it shows us?

The real issue concerning museum building as a possible form of critical praxis, are ways in which praxis can contribute to questioning the dominant hegemony. Once we accept that identities are never pre-given but that they are always the result of processes of identification, that they are discursively constructed, the question that arises is the type of identity that critical artistic practices should aim at fostering.

Peter Mayo, who writes on both Gramsci and Freire, asks a simple question that all political (meaning all) education must ask itself: “what side are we on when [we] teach, educate and act?” The ‘postmodern condition’ has now cornered us in a seemingly impossible situation –we are compelled to seek alternate histories in order to achieve an impossible balance between knowledge and the power it produces.

In postcolonial theory, unlearning dominant knowledge has been repeatedly discussed as an important practice for challenging the value-encoding apparatus from inside the structure of knowledge production. Is it even possible to simply leave dominant knowledge behind?For us, the answer is clear – there is simply no way back to a time or place before the history of relations of power and violence that are responsible for what we know today. For us, it is an absurd position, one that may even support the hegemonic power relations at play; “unlearning” is not merely interested in finding ways to avoid hegemony, but instead in formulating counter-hegemonic processes. Unlearning therefore neither involves imagining going back to a time before the current power relations were in place, nor a clear-cut correction process. It is about naming and thereby socially transforming histories of violence and spaces of agency created by resistance and struggles for liberation. In this sense, it is a form of learning that actively rejects dominant, privileged, exclusionary and violent forms of knowledge and acting, which we still often understand as education, and knowledge.

The Museum will lead us in directions of knowledges we didn’t know we needed to ask.

We at Museum of Impossible Forms wish to complicate the words ‘Museum’, and ‘Impossible’. For us, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. The ‘Museum’ no longer represents the ivory towers and petrification machines, where objects are preserved and inventoried in accordance with their cultural and historical ‘value’. Rather, they must take upon themselves to (re) establish their relationship to society and take on the role of being educational.

Museums today must ask on a regular basis, what must be done? Not just for itself, but for us, as members of a socio-political society. It must ask, how do we choose to act? How do we choose to act – In our media saturated, Socially omnipresent, politically fractured, economically segregated, Xenophobic, Disembodied world?

The question that we at Museum of Impossible Forms are asking is, “How can we propose an alternative?”

Where is our agency?

To speak up

To speak out

To critique

To transform

To impact

To take space

To make space

To give way

To see

To listen

To be heard?

Museum of Impossible Forms is a partial response towards the engulfment of a responsibility to facilitate and/or empower the facilitation of a new kind of para-institution, as a space for learning, unlearning and relearning; as a space to listen and be heard; and as a space that constitutes our own, collective yet personal ‘Atlas’.

Atlas of Lost Beliefs (for Insurgents, Citizens, & Untitled Bodies)

Curatorial text by Ali Akbar Mehta, Museum of Impossible Forms, Helsinki

The Atlas is ‘a book of maps or charts’. We gazed into the Atlas and dreamt of places we would like to visit. The Atlas was our window to strange and alien worlds, connected by an incomprehensible amount of water. Today, the Atlas as a portal, as a device for dreaming is a forgotten artefact, instead mired in historiographies and anthro-political readings of a world that was. Even now in a time obsessed with the past, devoted as it is to the cult of memory and the fetish of heritage, something still goes forward. Even now when there is no general direction, nor a subject who is supposed to lead, we cannot but ask where to place our next step, what to take along or leave behind. Yet there are still prospects, or in philosopher Bruno Latour’s words, “the shape of things to come.”

This future-forward projection of culture is enacted, in part, by Museum of Impossible Forms, because that is what we choose to do. Choice here is active participation.

In the poem, Atlas of Lost Beliefs, Ranjit Hoskote evokes an excerpt, a glimpse of a possible host of personas, both real and fictional, whom I can’t help but read as being ‘fellow insurgents, citizens, and untitled bodies’, all trying to swim in contaminated circumstances, to stay afloat in the infinite waters of precarity, seeking footing despite their groundlessness, subaltern characters not so very different from all of us – we are or have been each of them at some point in time, often all three, simultaneously, silently. And so we dedicate the coming year in solidarity with these, the cast of our collective narratives that connect the waters of our Atlas, who frame and address the engagement of cultural production with political and cultural predicaments in locations not ‘their own’ – whether described from a narrowly territorial point of view or within the contexts of secular, transnational, democratic, decolonial, queer, norm critical world(s); who allow us to ask, ‘What comes next?’

What can we learn from the Museum beyond what it shows us?

The real issue concerning museum building as a possible form of critical praxis, are ways in which praxis can contribute to questioning the dominant hegemony. Once we accept that identities are never pre-given but that they are always the result of processes of identification, that they are discursively constructed, the question that arises is the type of identity that critical artistic practices should aim at fostering.

Peter Mayo, who writes on both Gramsci and Freire, asks a simple question that all political (meaning all) education must ask itself: “what side are we on when [we] teach, educate and act?” The ‘postmodern condition’ has now cornered us in a seemingly impossible situation –we are compelled to seek alternate histories in order to achieve an impossible balance between knowledge and the power it produces.

The Museum will lead us in directions of knowledges we didn’t know we needed to ask.

We at Museum of Impossible Forms wish to complicate the words ‘Museum’, and ‘Impossible’. For us, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. The ‘Museum’ no longer represents the ivory towers and petrification machines, where objects are preserved and inventoried in accordance with their cultural and historical ‘value’. Rather, they must take upon themselves to (re) establish their relationship to society and take on the role of being educational.

Museums today must ask on a regular basis, what must be done? Not just for itself, but for us, as members of a socio-political society. It must ask, how do we choose to act? How do we choose to act – In our media saturated, Socially omnipresent, politically fractured, economically segregated, Xenophobic, Disembodied world?

Museum of Impossible Forms is a partial response towards the engulfment of a responsibility to facilitate and/or empower the facilitation of a new kind of para-institution, as a space for learning, unlearning and relearning; as a space to listen and be heard; and as a space that constitutes our own, collective yet personal ‘Atlas’.

[1] Ranjit Hoskote, ‘Jonahwhale’, Penguin Random House India, 2018, p. 7

Read more texts on the Museum of Impossible Forms website here

How to be a hospitable without being a motel: Thinking Hospitalities

Rehearsing Hospitalities Companion 1, (ed.) Yvonne Billimore and Jussi Koitela, (pub.) Archive Books, Berlin, in collaboration with Frame Contemporary Art Finland, Helsinki, FI

Museum of Impossible Forms (m{if}) is a cultural centre run by artists/ activists/ curators/ philosophers/ hustlers located in Kontula, East-Helsinki. Within the method of exchange, we strive to work with the existing culture(s) of Kontula and East Helsinki, with specifically seeking to develop a relationship with the organisations, projects, commercial shops, and community nodes in the area. We equally wish to participate in the continuous flow of an emergent culture that develops daily inside and outside the premises of the Museum of Impossible Forms, and the Kontula mall spaces.

We are striving towards para-institutional culture that focuses on ‘Alternate Pedagogy’ through the use of space at Museum of Impossible Forms – essentially, a multilingual library and multimedia archive; as well as a workshop and exhibition space. It facilitates curated discursive art programs, with an opportunity for norm-critical dialogue framed within the discourse of decoloniality, intersectional feminism, and queer theory. These equally create a complex mind-space fuelled by these socio-political ideologies that are shared by the members of the m{if}, and that becomes visible through our various efforts. That is, we want to be hospitable, but we are not a motel, we want something in return. As in, the basis of all our practice is that we are positioning ourselves within this specific political context and request that all whom we work with builds that basis with us, or at least is willing to engage with it.

Since its formation, the philosophy of m{if} as a collective and as a space has been concerned with issues of community, sharing, collaboration and hospitality. What is meant by hospitality pragmatically can take many forms? Essentially hospitality involves ‘care’ as a central node in the m{if} scheme. This often means addressing often overlooked elements of practice such as thinking about creating a sustainable and welcoming environment at our events, including accessible facilities and food. The notion of care extends from these elemental aspects towards more complex issues of economics and labour politics. Museum of Impossible Forms is a free space with the mandate to make available our resources (archive, library, workshop) and expertise to the surrounding communities. Furthermore, we compensate invited guests, artists, curators and speakers to support the integrity and ethics of cultural labour which is all too often underpaid, and underappreciated.

Care and consciousness towards ethical labour practices also mean that Museum of Impossible Forms is a safer space in more ways than one. Not only does m{if} advocate for safer space in its usual articulations of “(a) a supportive, non-threatening environment that encourages open-mindedness, respect, a willingness to learn from others, as well as physical and mental safety; (b) a space that is critical of the power structures that affect our everyday lives, where power dynamics, backgrounds, and the effects of our behaviour on others are prioritized; and © a space that strives to respect and understand survivors’ specific needs” – it is also a space that specifically entangles different realities and experiences with collaboration, participation and a space for the audience that is prompted by ideas of utopia and oppression, history and the future, borders, time, art and technology, and, more importantly, community. Live conversations, travelogues, discussion sessions and performances, and exhibitions of new and archival material interrogate our shared histories and forge new collaborations across time and space.

Relationship to knowledge and ways of knowing

A desire to work within the ‘centre/margin’ binary, presented in a geographical and ideological case, and the increasing need for para-museums such as m{if} to facilitate platforms of alternate pedagogies, has been instrumental in defining the space and our collective praxis within it. Peter Mayo, who writes on both Gramsci and Freire, asks a simple question that all political education must ask itself: “what side are we on when [we] teach, educate and act?” The question that we at Museum of Impossible Forms are asking is, “How can we propose an alternative?”

Where is our agency?

To speak up

To speak out

To critique

To transform

To impact

To take space

To make space

To give way

To see

To listen

To be heard?

We at Museum of Impossible Forms wish to complicate the words ‘Museum’, and ‘Impossible’. For us, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. Museum no longer represent the ivory towers and petrification machines, where objects are preserved and inventoried in accordance with their cultural and historical ‘value’. Rather, they must take upon themselves to (re)establish their relationship to society and take on the role of being educational. For us, the Museums today must continue to ask on a regular basis, ‘what must be done?’ Not just for itself, but for us as members of a socio-political society. It must ask, how do we choose to act?

Towards Gathering for Rehearsing HospitalitiesFor Gathering for Rehearsing Hospitalities, Museum of Impossible Forms will non-perform ‘A series of soft gestures towards Hospitality’ These gestures will be the result of direct/indirect collaborations between Frame Contemporary Art Finland, Museum of Impossible Forms, nynnyt, Asematila, Artist Collective Bread Omens (consisting of Jani Anders Purhonen and Elena Rantasuo), Heidi Hänninen, Bread makers from Tikke Restaurant, as well as other invited guests and participants from Kontula.

The First gesture of Hospitality is to invite and welcome people into one’s own space, of relinquishing agency and authorship

Museum of Impossible Forms welcomes and opens its doors to the organisers, invited speakers, and guests of Frame’s ‘Rehearsing Dialogues’, a series of conversations, discussions, presentations, and happenings performed daily.

Devising together the tools required to counter Institutional Hegemony is the Second gesture of Hospitality

We will host nynnyt, a feminist collective duo consisting of Selina Väliheikki and Hanna Ohtonen, who will open the space through a workshop on ‘How to work responsibly with Imperfect Tools’. Through their talk, they will outline complexities within Finnish Contemporary Art spaces and the problematics within the Institutional spaces.

The exploration of sustenance and sustainability is the Third gesture of Hospitality

In Collaboration with Asematila, Museum of Impossible Forms will co-host Bread Omens as an installation and para-site event in Kontula Mall, in front of the Kontula Public Library; where they will be exploring bread-making as a method for building and sustaining communities.

To participate with and involve those who live amongst us is the Fourth gesture of Hospitality

Along with artist and activist Heidi Hänninen, the project will work with sister institutions within Kontula to host a series of workshops aimed for residents of Kontula.

Producing and Transmitting Knowledge is The Fifth gesture of Hospitality

Museum of Impossible Forms and Asematila will conceive and present a ‘Bread Archive’, a multi-sensory installation as a method to bridge the two spaces through epistemological knowledges, in this case of bread and its histories within Finnish Cultural memories, within its contemporary fabric and the entanglements of purity, immigration, refuge, borderless-ness, community and participatory knowledge gathering.

Re-Musing the Museum: Part II

ArTalk: Just Art? Ethics, guidance and art autonomy, Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, 2018

Re-Musing the Museum: Part II was a talk presented in my capacity as Co-Artistic director of Museum of Impossible Forms, discussing the precarity of cultural work in the context of Museum work.

[I]n today’s information society, museums have an important role to play in preserving, producing and transmitting information. However, as cultural funding continues to decline, the responsibility for producing information and culture increasingly shifts to the individual: the museum worker, the artist, the spectator and the experiencer, the museum visitor, the curator. How can museums redefine themselves in a rapidly changing world?

This was the first event in the ArTalk series titled ArTalk: Just Art? Ethics, guidance and art autonomy was organized by TAKU Ry (Culture Worker’s Association) and MAL Ry (Museum worker’s Union), on 27 November 2018 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma.

Below is the text of my prepared lecture performance:

Re-Musing the Museum, Part II

Good evening,

My name is Ali Akbar Mehta. For those of you who do not know me, I am a Transmedia artist, living now in Helsinki since 2015. My practice involves creating immersive archives that orbit the themes of violence, conflict and trauma. I am also one of the founding members of Museum of Impossible Forms, and currently one of the three Artistic Directors that are involved in the core programming of the space.

I am here to briefly talk about ethical and political action within a museum space, and share some of the work we do at Museum of Impossible Forms. I can begin by providing some kind of a contextual framework that seems relevant in why we do… what we do at Museum of Impossible Forms:

We are living in a ‘knowledge based’ society, where intellectual labour has a dominant form; and that the ability to communicate, to act autonomously and to produce knowledge are the requirements for being creative, creating and consuming knowledge. “Knowledge has to be produced somewhere […] once produced, it has to be transmitted […] this transmission will by necessity imply a pedagogical element.” One also assumes that if knowledge is of increasing importance today, institutions of both creating and transmitting knowledge must be important – But reality disproves this assumption as we witness a deterioration due to lack of funding, thereby ruining academies, universities and institutions; and defunding and cuts in culture sector reducing the effectiveness of artistic endeavours.

Sooner or later we will reach a knowledge society without knowledge. Worse, society will transform into a society with very specific kinds of knowledge – those that have immediate relevance in the job markets. The role of education to impart knowledge based on economic gain is a crucial statement of fact indicating the state of government policy, the dominating corporate sectors and diminishing role of universities.

The burden of producing knowledge is therefore increasingly shifted onto the individual ‘User’. The ‘User’ here is simultaneously an archivist/ artist/ curator/ author/ researcher/ participant/ audience. Museum of Impossible Forms recognizes the implied urgency within this crucial fact and its own role as a para-institution focusing on alternate pedagogy.

**

And so, The question that we at Museum of Impossible Forms are asking is, “How can we propose an alternative?”

Where is our agency?

To speak up

To speak out

To critique

To transform

To impact

To take space

To make space

To give way

To see

To listen

To be heard?

Ethnocentrism is a dominant, normative and often hegemonic thinking that would have all of us, as individuals, believe that ‘My Culture is better than yours’.

Conversely, The act of being a student is a performative act. It is an act that actively disengages with the statement of ethnocentrism, and states instead that ‘your knowledge is better than mine’. As students those who profess to be in a state of learning) we hope and claim to seek that knowledge by a seemingly simple acknowledgement ‘Your Culture is better than mine’. Of course, this statement is at least partially utopian if not terribly presumptuous. But I make it in the face of the current ethnocentricity that has seemingly shaped our understanding of history, a history of struggle, of conflict and violence, and other relations of power structures.

In postcolonial theory, unlearning dominant knowledge has been repeatedly discussed as an important practice for challenging the value-encoding apparatus from inside the structure of knowledge production. Is it even possible to simply leave dominant knowledge behind? For Nora Sternfeld, the answer is clear – there is simply no way back to a time or place before the history of relations of power and violence that are responsible for what we know today. For her, it is an absurd position, one that may even support the hegemonic power relations at play; “unlearning” is not merely interested in finding ways to avoid hegemony, but instead in formulating counter-hegemonic processes. Unlearning therefore neither involves imagining going back to a time before the current power relations were in place, nor a clear-cut correction process. It is about naming and thereby socially transforming histories of violence and spaces of agency created by resistance and struggles for liberation. In this sense, it is a form of learning that actively rejects dominant, privileged, exclusionary and violent forms of knowledge and acting, which we still often understand as education, and knowledge.

For me , Museum of Impossible Forms is a partial response towards the engulfment of a responsibility to facilitate and/or empower the facilitation of a new kind of para-institution. The main aim of all activities, events, and programs, is to continue to investigate the foundation on which M{if} is proposed, which is: To create a space that facilitates the creation of emancipatory knowledge that upholds the principles of decoloniality and equality, within a larger framework of ‘Alternative Pedagogy’ and ‘Para Institutional Spaces’, as a space for learning, unlearning and relearning.

We at Museum of Impossible Forms wish to complicate the words ‘Museum’, and ‘Impossible’. For us, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. Museum no longer represent the ivory towers and petrification machines, where objects are preserved and inventoried in accordance with their cultural and historical ‘value’. Rather, they must take upon themselves to (re)establish their relationship to society and take on the role of being educational.

Museums today must ask on a regular basis, what must be done? Not just for itself, but for us as members of a socio-political society. It must ask, how do we choose to act? How do we choose to act – In our media saturated, Socially omnipresent, politically fractured, economically segregated, Xenophobic, Disembodied world?

Where ‘post’ in Post Adolescent, Post Modern, Post Human, Post Jargon, Post Truth, Post Fordist, Post History, Post Colonial, Post Humour, Post Meaning, Post Apocalyptic, Post Graduate, means, ‘In crisis of’.

As the poet and philosopher Sun Ra has said,

“The possible has been tried and failed. Now it’s time to try the impossible.”

And so , if you will repeat after me, “Museums:

- Museums, are archives of knowledge

- Museums, preserve patrimony and cultural heritage against vandalism, oblivion, or decay

- Museums, manifest concerns of the epochs

- Museums, are sites of exclusion

- Museums, mirror dominant ideologies

- Museums, are neutral a(n)estheticized frameworks for artists

- Museums, are none of the above

- Museums, are all of the above

- Museums, are more than this list

- We, as ‘users’ will seek new meanings for what can it mean for ‘the Museum; to be an ‘Impossible Form’.”

As a ‘User’ working to create immersive archives, working with archives and intimately involved in the manifestation of a space, its core programming and its ‘becoming’ in its physical space, The concepts of ‘Archive’ and ‘Museum’ remain distinct, become blurred, intersect, and often merge. I invite you freely entangle the two in the following: