Ballad of the War that Never Was, and Other Basterdised Myths

- Ballad of the War that Never Was, and Other Basterdised Myths

- Not on Noah’s Ark, but on the Raft of the Medusa

- Somewhere between Science and Subjectivity

- Paintings

- Drawings

- The Harlequin Series

- Everybody's a Jester

- Ballad of the War that Never Was, and Other Basterdised Myths, TAO Art Gallery

- In A Liminal Age

- Comprehending Violence

- Nothing is Mundane

“Mehta is an explorer charting a demon-haunted world that balances precariously between compassion and oppression, instability and militarisation; the mushroom cloud of nuclear annihilation is always billowing on its horizon.”

Not on Noah’s Ark, but on the Raft of the Medusa

Essay by Ranjit Hoskote, Mumbai, 2011

Normality is the somewhat misleading name that many of us give to the present. It is often the only means of remaining sane while enduring the abrupt horrors and dehumanising provocations that surround us. The artist, however, is not obliged either to neutralise himself to these horrors and provocations; nor is he afraid of exploring the regimes of consciousness that lie beneath the sanctioned threshold of sanity.

And so the jesters, harlequins, cerecloth-swaddled zombies and explosion- flayed refugees who populate Ali Akbar Mehta’s paintings and digital works are not strangers. Not at all, for we know them intimately well, these figures who dominate the 1983-born Mehta’s first solo exhibition: they are ourselves an hour from now, a decade from now, in the near future, or at any moment. Allegories of the present, veiled thinly as a post apocalyptic future, Mehta’s works alternate, tonally, between melancholia and the ludic, between Lent and Carnival. They emerge from a long tradition of critique-through-image that turns our conventions of time, space, gravity and propriety topsy-turvy: a tradition that counts, among its major exponents, Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel.

On the testimony of these works, produced between 2006 and 2011, Mehta is an explorer charting a demon-haunted world that balances precariously between compassion and oppression, instability and militarisation; the mushroom cloud of nuclear annihilation is always billowing on its horizon.

*

Mehta is a member of what has been called the generation of ‘digital natives’, who grew up with personal computers, wireless telephony, and electronic retrieval systems of every size and scale. The translation of substance into immaterial form is a basic parameter of the lifeworld he inhabits; with it comes the understanding that data flows rather than being confined, and that images and episodes too are part of ongoing, vast narratives rather than remaining in guarded pools.

Having been exposed to animation as a creative form in his parents’ animation studio, Mehta also embraces comic books, graphic novels, manga and anime as cultural resources.

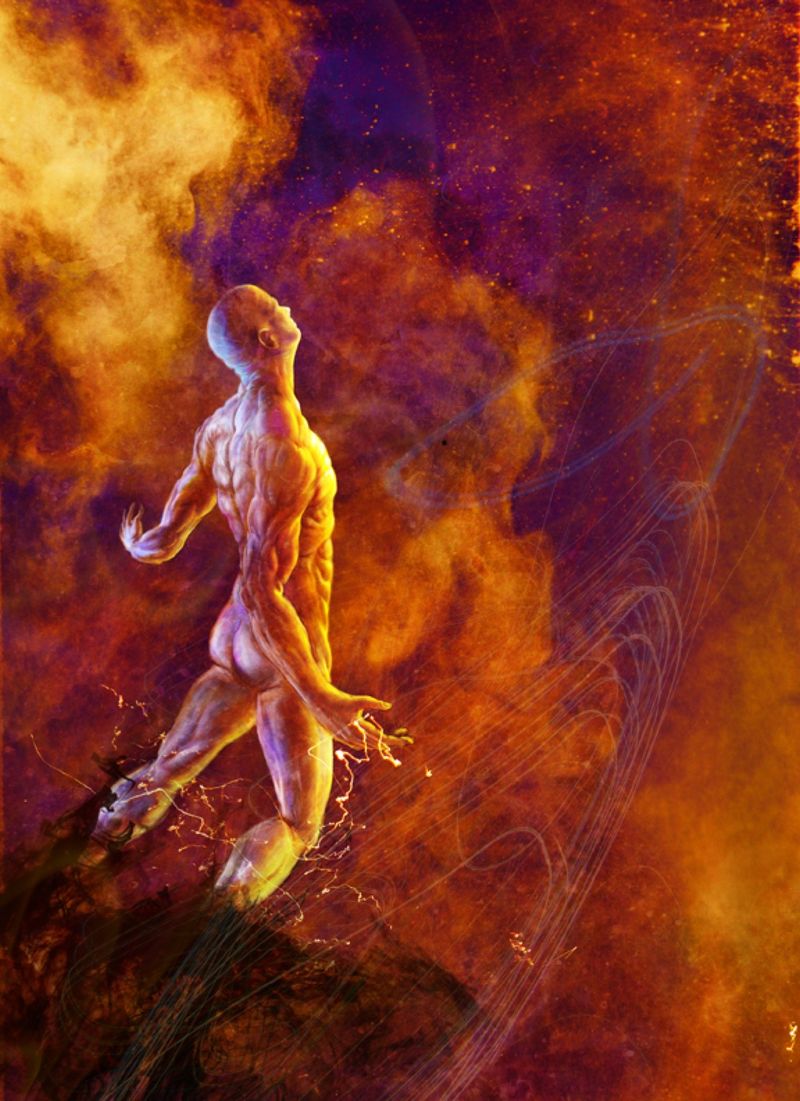

Ali Akbar Mehta_Harlequin Series; To Glory in Self, like some kind of New Monster, 2010, Archival print on Hahnemuhle paper, 182 x 121 cm

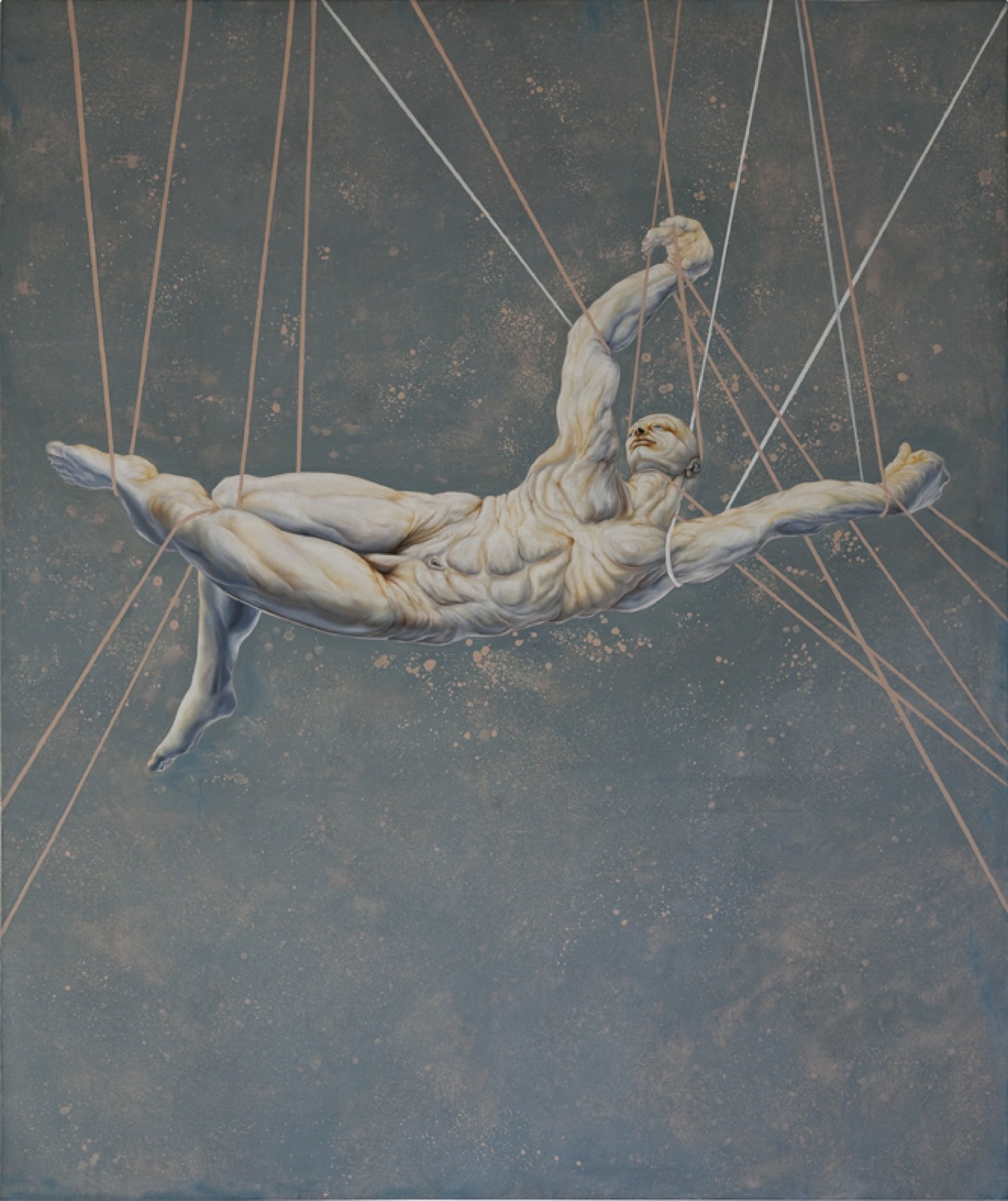

Naturally, then, Mehta is fascinated by the figure of the superhero: who is supremely powerful yet deeply vulnerable, benevolent yet sinister, weighed down by the knowledge of humankind’s ultimate fate yet aware of his role as a guardian of hope and renewal. If the archetype of the great hero enshrines the spirit of indomitable resilience, it also incarnates all the freight of fear and paralysing anguish to which humankind is heir. In many of Mehta’s figures, the ligaments are stretched, the bone is set at breaking point. Indeed, in Mehta’s handing, the body is often an unsettling hybrid of muscular presence and spectral apparition: it is made, seemingly, of ectoplasm or pulp that has momentarily assumed a shape which it may lose without notice.

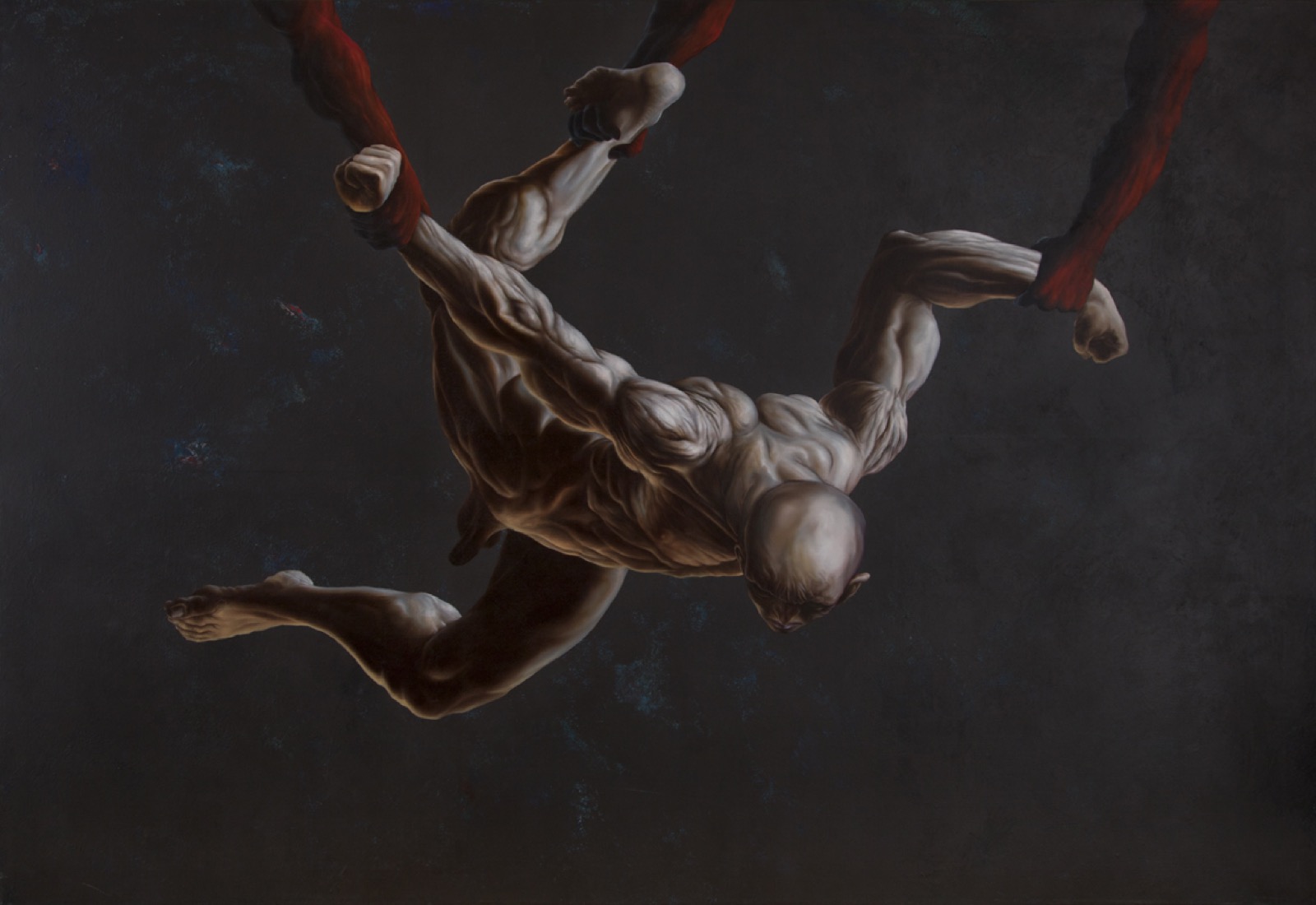

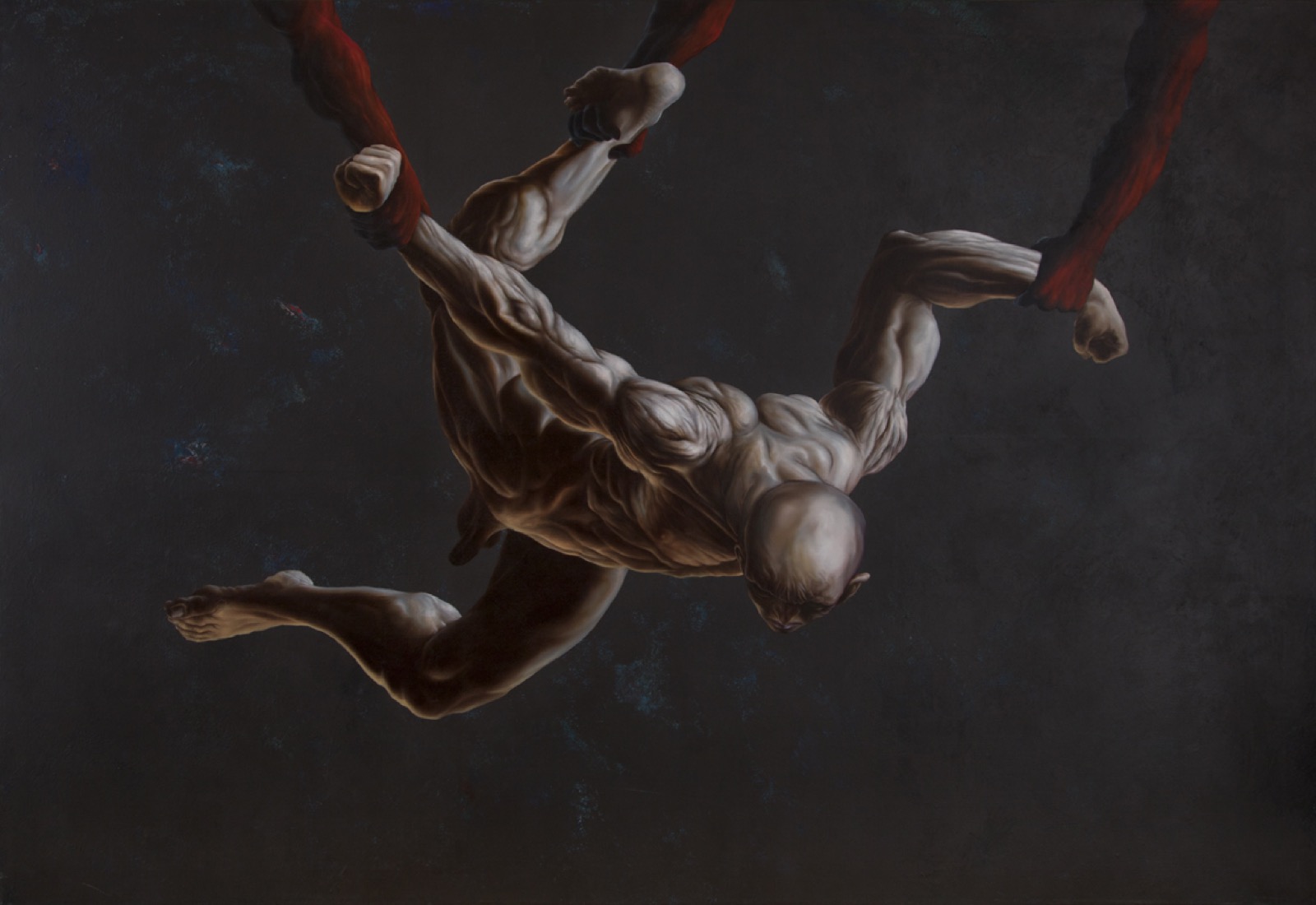

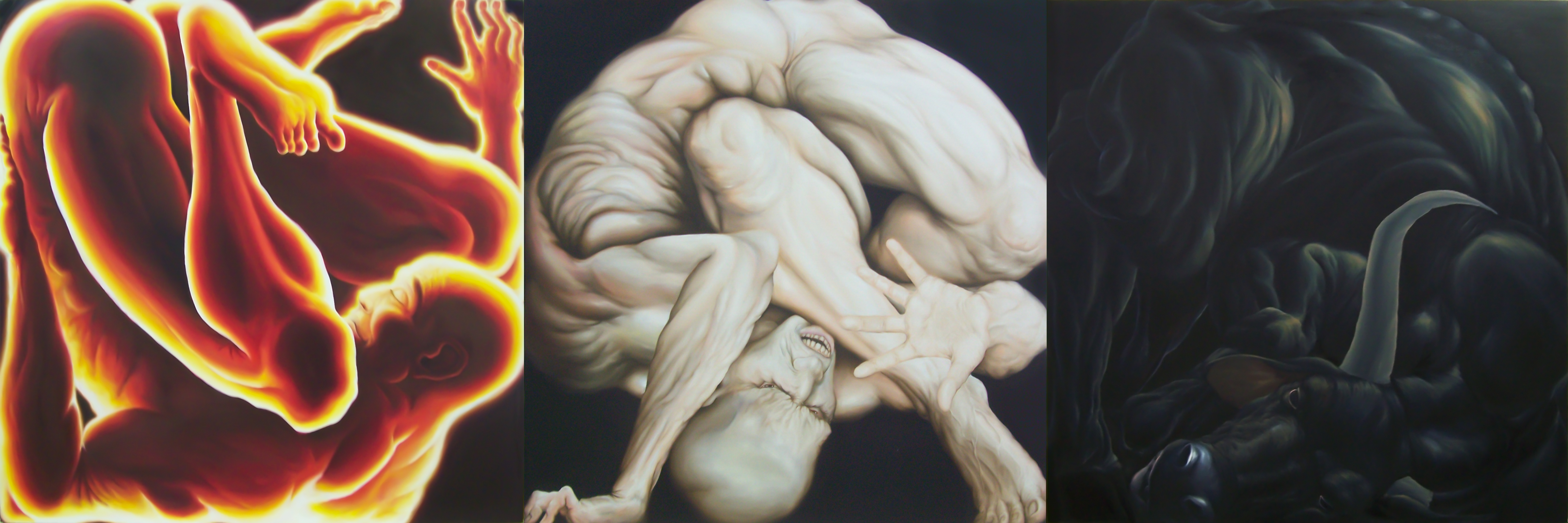

In Mehta’s imagery of the suffering yet defiant body, we may detect an act of homage to his grandfather, the legendary artist Tyeb Mehta. We find this especially in the trussed figure, suspended from ropes, more prisoner than marionette and hung above the abyss, in ‘The Identity of Violence Series: Suffering and Rapture’(2010). That homage also animates the figure that has been twisted, knotted, folded double in ‘Triptych’ (2007) and jammed into the cage formed by the frame of the canvas.

Ali Akbar Mehta_The Identity of Violence Series; Sacrifice and Redemption, 2010, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 182 x 121 cm

*

Mehta’s preparatory process involves a theatre-like ‘characterisation’ of his protagonists: a detailed imagining of their ‘inner lives’, a fleshing-out of their ‘back stories’, a calibration of their emotional temperature based on episodes deemed to have taken place in the past of their fictive present scenarios. As in theatre, this characterisation is not made wholly explicit in the articulated form of the work; nor is it meant to be. Rather, it serves the artist as the substance that confers reality upon his characters, and is the continuing material substrate from which his images and the narratives that concern them will be conjured.

Mehta delights in portraying quixotic figures of unpredictable motivation as they move through the columned halls and terraces of normality, replacing these with the weaving shapes of hallucination and phantasmagoria.

*

Among his protagonists are the jester and the harlequin: the first permitted to speak truth to power, although in politically sanctioned satire and allegory; the second a shape-shifting trickster who celebrates all that is chaotic and out of joint. Accordingly, the artist favours a pictorial space that is psychedelic, its emphasis laid on the play of strange lights and pulsating auras. Indeed, to this observer, his canvases articulate the ominous psychological freight of Bikash Bhattacharya’s paintings of the 1970s.

Humankind lurches from one crisis to the next in Mehta’s post-apocalyptic ecologies, with little chance of redemption. We find predators and victims, survivors and demons, all conjoined in a common destiny, all adrift: not on a Noachic Ark so much as on a Gericauldian Raft of the Medusa. In the painting that gives this exhibition its title, ‘The Ballad of The War That Never Was’ (2010), one of the key figures is modelled on the Deposition, the enduring moment when the crucified Christ is taken down from the cross, except that this figure has no hope of resurrection; another figure in this tableau is based on Delacroix’s ‘Liberty Leading the People’, except that the banner is fraying, torn to pieces by the wind.

Ballad of The War That Never Was, 2011, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 152 x 198 cm

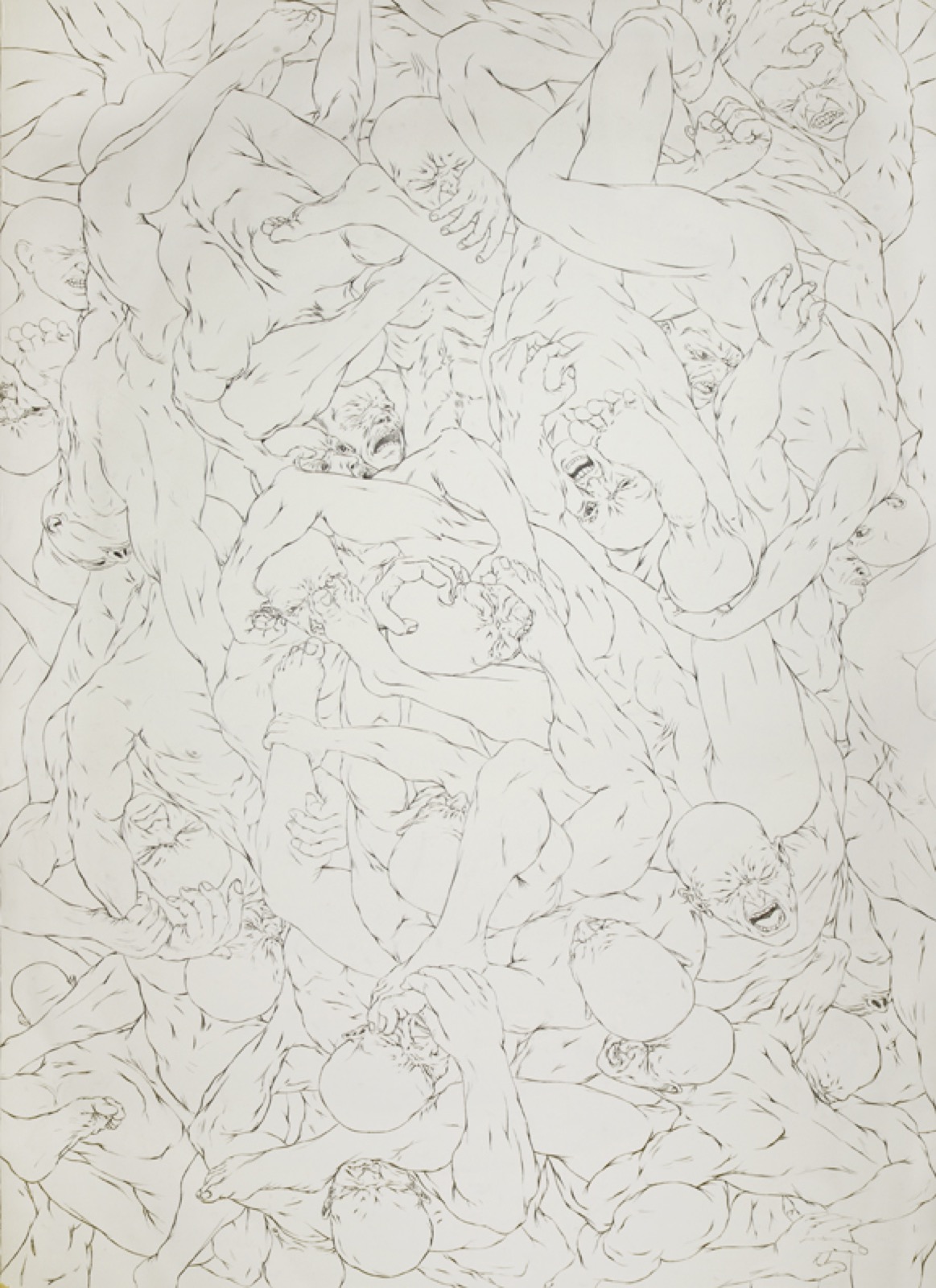

Or, as with the close-packed figures in ‘War’ (2011), screaming as they flail, wrestle and fall together in a grand tapestry of the damned, Mehta’s figures strike us as a contemporary version of Dante’s eternally condemned figures in the Inferno or Michelangelo’s in the Sistine ‘Last Judgement’. The mode of the history painting manifests itself again and again in Mehta’s work, through allusion and citation. But the inspired certitudes of history painting and its heroic belief in the ability of the human will to dominate all circumstance have yielded, in Mehta’s paintings, before a more tragic awareness of human fragility. This artist does indeed take man as the measure of all things, in the classical humanist formulation; but man is here a strained measure, bent under pressure. Precisely for this reason, Mehta’s protagonists speak to us of our own anxieties and exhilarations, sing to us of our own at-once epic and intimate predicaments.

Ranjit Hoskote

Mumbai, 2011

Somewhere between Science and Subjectivity

Interview by Rahul D'Souza

Meera Nanda’s concept of a hyper-spiritual and hyper-religious India, as a direct consequence of a global interest in Indic spiritualism and religion, is an interesting medium through which we can evaluate the identity of an Indian artist. With the world’s eyes on India as a culture, how can Indians portray themselves to be genuine? And consequently, how Indian are artists, writers, dancers, actors etc?

Can Ali be an Indian artist under these circumstances? Will his urban, western influences enable him to portray the true world of an Indian?

I am as honest as I can be about the way I see the world. I have an urban Indian upbringing. It is as influenced by the west as it is by India. I also have an interest in Japanese animation. I do not restrict my sphere of influence to one culture, nor do I try to channel just one culture through my work.

Yet my perspectives are those of an Indian. No one else in the world can see these things from the perspective of someone who has grown up in urban India. I also have the perspective of an Individual, no other Indian, urban or otherwise, sees India in the same way that I do.

I cannot have the perspective of a person from an indigenous group as I do not come from one, my perspectives are not feminist because I do not feel like I have the right or the inclination to make such portrayals.

This subjectivity has been a part of both Indian culture as well as religion for centuries at the Individual level, yet today this individualism is being suppressed through societal dogmatism – being a part of Indian society de-individualised, and, of course if we were to look at our own history we would see that much evil has been perpetuated in the name of societal dogma.

In the theatre of hyper-spiritualism and hyper-religiousness Ali’s work strikes me as being completely devoid of any obvious spiritual and religious depictions. It appears that the space is taken over by an overbearing humanism, especially emotion as portrayed by his harlequins. A simple question arises: Are your works secular?

I am not religious. I remember being an agnostic at some point in the past which slowly changed into a staunch form of atheism; now I no longer have the staunch convictions and find that I am an agnostic once again.

Many of my works are reflective of this personal questioning of religion – especially the religious strife that has engulfed India in my own lifetime. However, though these works begin with religious inspiration they soon become their own narrative.

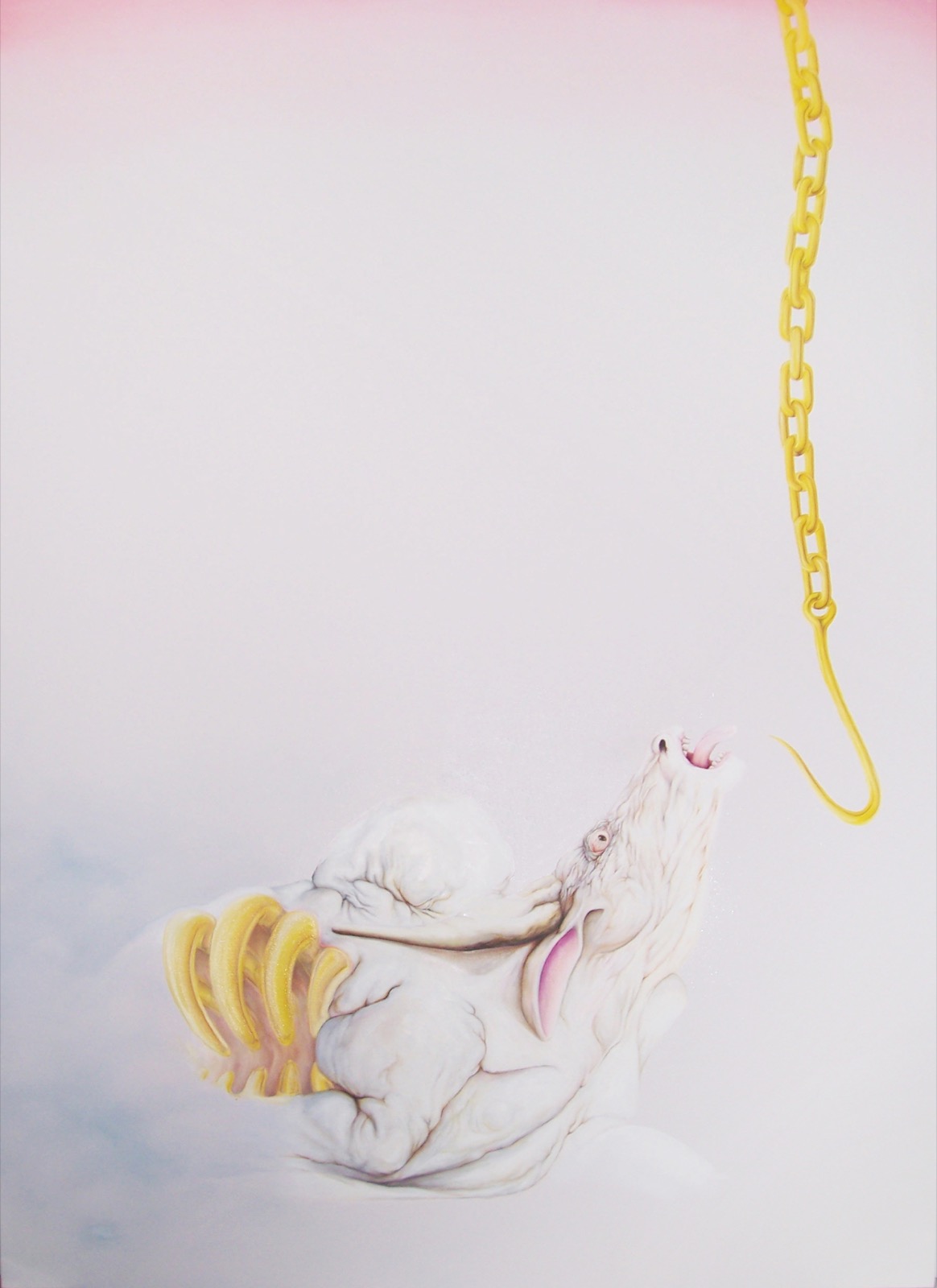

My work Shwet (2006) is a good example of the religious themes that may inhabit my work. This grotesque image is accompanied by words from a song by Jethro Tull that I feel perfectly illustrate what I wanted to portray in the painting. This painting speaks of the manipulation of innocents, of ideals, to suit the human recommended medium of satisfaction for the “creator”.

To fully appreciate Ali’s sentiment we must first establish what urban identity he possesses. Growing up in Delhi and Mumbai he not only experienced the Indian art circuit but also engaged with theatre and film. To this we must add musical influences like The Doors. Ali belongs to a very vocal minority that listens to British and American music, particularly what can broadly be called Rock.

It is through his love for The Doors that we can get an insight into this aspect of his identity. The Doors are still a popular band with young people in Mumbai. Jim Morrison’s large personality, the imagery of his poetic lyrics, and the magnetism of his voice are naturally attractive. However there is also a personality cult that has developed around him. The violence, the alcoholism and drug use attracts a whole new audience to the music. We can call this factor an extra-artistic reason for the popularity of The Doors.

Ali sees the band differently, particularly Morrison. This is as related to how he was introduced to them as how he identifies with the music at hand.

My dad is a huge fan of The Doors and their music has always been around me ever since I was a child. It’s only natural that I feel influenced by their music. For a very long time the personality part of Jim Morrison was not a factor in how I saw them. It was only later on in college when I met other fans of the band that I began to meet fans of the Morrison personality cult.

I don’t have any problem with fans of the personality of the artists but it is still not the way I see the band. Ultimately, as before, the work is enough to keep me engrossed and I do not need any extra-artistic reason to like them.

It is how I view art as well. If the work can stand on its own, that’s enough for me. The personality of an artist and even the personality of the work should only enhance understanding of the work; it must not make the work. Of course the art itself is a product of personality, but it is an abstracted part.

We must turn to the Stuckist manifesto, published in 1999 by Billy Childish and Charles Thomson, at this time in order to evaluate Ali’s methodology and conceptualisation.

Ali’s paintings seem to be a journey of self discovery. He keenly explores archetypes, which while penetrating human consciousness also does the same to the self. There is a hint of self-examination involved when the artist goes in search of base forms and expressions. To work with Jung’s archetypes is akin to examining the original forms present within the artist’s own consciousness. While Jung’s archetypal image provides an engaging explanation for the recurrence of form, especially in the past, between heretofore unconnected cultures its manifestation in human expressed form is portrayed through the lens of subjectivity. When an artist rejects the prevailing ideas of archetypal images, does he really reject them or does he merely reinterpret the archetype? Further, does the archetype really exist for any set of people in a homogeneously referable form or is it merely a collection of memes assembled individually?

The Image as archetype comes after a long process of inferences that can now be counted as milestones in my work. The question was of the nature and the purpose of art. Almost every form of plastic as well as performative art, whether cinema, video theatre, performance or music have inherently, a structure of the narrative, even a non-narrative narrative.

To my understanding, painting and photography are the only forms of art where the structure of the space time continuum is breached in such a drastic way. It is both a moment of time, a nanosecond, as well as the suspended animation of infinity, if one chooses to treat it so. It made me realise that the nature of image, therefore must be something that is worth talking about in those terms. As I said before, I was also questioning the role of art in those days. To my mind, a contemporary version of the iconoclastic imagery needed to be generated/found. The archetypal imagery of the kind of work that I was looking at needed to be replaced with newer, relevant iconography.

After exploration comes rendering. Ali’s medium of choice has been the canvas. Yet he also believes in the scientific tradition of progress – pushing towards newer ways to do everyday activities. This has heralded a shift from physical painting on canvas to working in the digital realm; a journey back towards his animation roots. This speaks as much about his love for and comfort with the digital medium as it speaks for how much he endeavours to improve upon his rendering to improve upon his emotional portrayal. While the harlequin, portrayed giving support to being the outsider viz. the tired Hero, on a canvas portrayal gives us subtle hints at the chaos at play, the digital works that involve the harlequin embody chaos in every stroke, every colour whose vibrancy would not be possible be difficult on canvas. This does not stray to far away from the Stuckists desire for experimentation and bold forays into the unknown, their desire to be wrong. It is a fact that Ali began experimenting with form and medium early in life, at school, where he used to sculpt on chalk. [I REMEMBER SURYANANDINI TALKING ABOUT THIS – PLEASE VERIFY] While Ali has not yet gone back to those early forays into sculpting, we can see the desire to understand both form and medium.

Can we safely call Ali a Stuckist, or more mildly that he follows in a Stuckist tradition? For every similar thought that he shares with the Stuckists, he seems to reject their rigidity. There is a deep desire for inclusion rather than exclusion.

I think the Stuckists had the possibility of making it a manifesto of all forms of sincere art instead of Stuckists vs the YBA-Tate.

I have been fairly anti-video in the Indian art scene, not because I am anti-video, but because I am anti-bad-video. There has been so much in the pursuit of better film making that is of a higher quality than the best video art available today. This is what the stuckists are talking about – when a person is painting he should be doing it with a complete understanding of what painting is (technically and artistically) and fulfil the potential there. I am disturbed by peoples comfort with the lack of definition in art in terms of medium, what is the difference between a video artist and an experimental filmmaker. The same applies for musicians, writers, etc.

Where people like YBA are rejecting painting as a genre for being traditional, here the stuckists are rejecting a whole genre in an evolving form. They are accomplices in that act of rejecting which is not really a solution – there needs to be a certain kind of clarity to know what it is you are doing and what it is they are doing; with differing agenda, audiences, etc but both equally valid.

Does this mean that Ali is against postmodern art but not the postmodern artists – in a manner of speaking yes. There is definitely potential in encouraging a postmodernist to go beyond mere conceptualisation and explore better artistic technique to express what he envisions. Yet, they need not restrict themselves to just painting. What is important is that the artist explores and creates rather than designs for manufacture.

I remember Damien Hirst using Latin, biblical references, etc to bring across an atheist perspective in his conceptual works – would people take this serious if it were just paintings. I don’t really have a problem with his material media – it’s not the artist who is at fault, but people who blow it out of proportion.

This whole idea of rejecting other forms of art for the sake of rejection is different from my own thoughts on changing art. If you are doing performance, are you taking into account the prehistory and history of performative art? Taking into account Neanderthals, prehistoric man, Shakespeare, Greek theatre, dance etc. We have a whole Natyashastra talking about various aspects about performance. Are artists today taking into account this performance history?

There is an overhanging question then of what constitutes and artist and an artisan or in our modern urban settings a designer. Haven’t artisans and designers continued to explore technique and portrayal which fine artists had discarded for decades? What about filmmaking and filmmakers? How do we differentiate between the filmmaker and the filmmaker artist?

We are looking at a certain visual history that a painter is concerned with, what for a painter is not mainstream are they aligning themselves to that? They are not they are creating a new terminology. They are completely bypassing the existing genres – this distinguishes a sound artist from a musician and other such examples.

I’m not saying that this is an artist and this is not, they are all artists. Does a painter who is a filmmaker get affected by filmmaking when painting? When Husain and Tyeb Mehta made films they made short films, Husain even making mainstream movies – there is a difference in the way they deal with the medium of cinema when comparing this to filmmakers. How do you envision a single moment of time in painting and transferring it to the constant change of the medium of cinema. The process of painting has such a different pace from the long drawn out structured process of filmmaking.

I find that a lot of video artists don’t understand the medium they are working in because of their training as sculptures and painters. Shilpa Gupta is among the last artists looking at a new medium, alien to them, and trying to educate themselves in it. After that there are many artists who just take it too lightly.

***

Where a person derives identity from is as important as the identity itself. Evident in Ali’s work is the presence of characters from a particular genre of storytelling. Mythology manifests itself through the span of his work. The Apollonian hero and the Dionisysian harlequin are lead characters, so to say, on his stage/canvas. The presence of the hero and the harlequin are gateways to the journey undertaken by the artist to reach the point at which he is today.

I am very intrigued by the story of the ideal hero or rather the form of the ideal hero. The hero, be it in Greek mythology or in the form of modern day comic books is a character that humans aspire to become, yet, we find that he has to channel human suffering through him placing an immense weight upon the self.

In contrast, the harlequin is far more versatile character – the mischievous creator of chaos must reveal himself through a variety of roles, where the hero is restricted to a uni-dimensional role, accepting and then struggling against suffering, the harlequin revels in chaos and suffering. When an actor wears a mask, he does not act according to a script alone, but must become in being the person that the mask is depicting. The harlequin is a masked actor. He has forgone any identity other than the one that has been bestowed upon him. The chaos he unleashes is fashioned in the nature of the harlequin itself. It lies within the basic characteristic of the depiction. We must not marvel at a good actor but rather marvel at the audacious creature that the actor has become.

The neutral emotive space is as important to the work as the subjects you find occupying them. Deeply similar to theatre, to which the artist has a strong familial link, Ali’s work dominates the space with its cultural ambiguity, not as an object that rejects cultural context but as an actor that chooses which aspects of its personality it should reveal and which should stay hidden.

The first time that I saw Ali’s work I was filled with the kind of pretention that engulfs art history graduates for a few months after their course is completed – I had been trained to over articulate and and overemphasise every clue of repression, every cultural reference, every farfetched, convoluted explanation in art. Secretly I had an inner rebellion against this avant-garde-ist view of art, culture and philosophy.

Sat in front of a computer I watched as Ali sketched out story boards for an animated movie. Two things strike me today about that day: 1) I was struck by the daring of an artist to bring so much figuration, technique and emotion into his work and 2) Unknown to me, I had just had a glance at the very genesis of Ali’s development into an artist. While we cannot deny his own artistic heritage, Ali’s introduction to art was actually through animation.

__

Many people think I am an artist because of my grandfather, that I was even directly influenced by him. I will not deny an awareness and admiration for his work I wanted to be in animation. Another factor was that I had spent a considerable time living in Delhi away from my grandfather.

When I went to J.J. it was not to study fine art but to hone my skills for animation. I even ran an animation studio for years after I had graduated. I reached the place that I am today gradually, painting on canvas. Over time I exhibited and sold a few works. You can see animation’s influence in my paintings not only in aspects of the rendering but also in my themes and references.

I am also deeply influenced by the format of the graphic novel. While it is the storyline that lends the emotion, and the narrative, it is the rendering of the characters that really is the important thing. That a graphic novelist can in one box, with a single character create a multiplicity of emotions, clues about character and do it without text is at the very height of artistic portrayal. This is the artist as the actor, this is worth aspiring for.

Rahul D’souza

Rahul D’souza has a MA in the History of Art and Archaeology from the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. He currently works in the Editorial Department at Marg. He is also a writer and blogger and co-founder of the culture blog http://www.thecityslacker.com. Among his areas of interest is to bring about a unity between art and western science and to work towards the public understanding of early South Asian civilizations.

This essay is based on several conversations between Ali Akbar Mehta and the writer over the last two years. To avoid confusion the “voice” of the artist is set in italics.

Paintings

Drawings

The Harlequin Series

The Harlequin

The Harlequin appears in Dante’s Inferno “roaming the streets with a band of devils, searching for souls to drag back to Hell”; In Medieval French miracle plays; to more positive and mystical interpretations with a multi-colored diamond-patterned costume that embodies the many-sidedness and richness of life.

The Harlequin - almost Dionysian in the liberating chaos of life is in opposition to the central figure of the canvas works - the Hero of human myth - Apollonian in seeking order and fulfilling his destiny. The Harlequin is a prankster and trickster, intrusive and greedy, always ready to lie, an anarchist reveling in chaos. But he is also witty and carefree, exuding innocence and naiveté. He is nimble and light, made of air, physically and morally flexible. He is an embodiment, simultaneously, of the light and the dark, and the minute infinite layers of gray that make up the composite of human beings.

The Harlequin exists is in a world alien to ours; a surreal world of chaos, dreams and constant flux. A virtual world, a world without texture, plastic, strange. The world of the Hero even though stripped of cultural markers and non-specific to any culture is still within the physical known realm. The physical medium, therefore, of oil on canvas of the Hero, becomes inadequate for the Harlequin. The polarity of the ‘Noble’ and self sacrificing Hero and the Harlequin is reflected in the polarity of the two worlds, and the two mediums. The organic and the physical world of the hero, and the synthetic, artificial and virtual world of the Harlequin. The non-destructive easily malleable easily changeable nature of virtual world of the computer becomes in fact the ideal medium for creating this world of the Harlequin.

Chaos in the physical world exists at a level not perceived by human senses. The nature of human consciousness is one that seeks to impose order and patterns into seemingly random events. The computer as a tool provides a non-human intervention in bringing a degree of controlled randomness. It creates a parallel universe and space-time continuum

Everybody's a Jester

Ballad of the War that Never Was, and Other Basterdised Myths, TAO Art Gallery

In A Liminal Age

Interview by Rahul D'Souza

Ali Akbar Mehta talks candidly with Rahul D’Souza about his first solo exhibition, “Ballad of the War that Never Was and other Bastardised Myths” (unpublished)

Rahul D’souza: Tell us about the title of your show “Ballad of the War that Never Was and other Bastardised myths”. What did you envisioned when you came up with the title?

Ali Akbar Mehta: The idea of the title “Ballad of the War that Never Was” actually came from an increasing preoccupation that I have been having with the idea of violence, of how our world is governed by responses that are majorly violent…

The opening line of my Artist Statement says, “Interactions between individuals, communities and nations are driven largely by instinct to establish dominance in territory”. When I considered the title I wanted it to be representative of the whole body of my work. I realised that most of my work had to do with the nature of the violence we experience – consciously or unconsciously; whether it is intra-personal relationships or international events. Since I’m not speaking about the whole idea of a specifically driven war, a specific political context or a social context I thought it would be interesting to call it “The War that Never Was”.

RD: So, because it’s a collection of violence, it doesn’t mean that the war never took place, it just never took place together in the way that you are envisioning it. Things may or may not already have occurred.

AM: I think it gives me an opening, to be able to look at war as a series of events that have taken part in the entire history of human existence rather than one particular war. It gives me a chance to look at the whole universal manifestation of that idea of war as violence and smaller scale violence as war. Even the painting Ballad of the War that Never Was is not based on any specific war, it is the human emotive, what would be conveyed in a war.

RD: Do you feel that the violence, and suffering from violence is caused by human desire to break free from our own earthly bounds, the struggle between the material and the spiritual world, the desire for something higher is a starting point for us to look at violence, even though the works are completely devoid of the cause in the end? Is it the beginning of your process?

AM: Yes, I think war has certain kind of a situation that inherently exists because of a certain lack of understanding of the differences in culture, differences in perceptions, or differences in ideas of what is right or wrong.

RD: … or even a specific Individual difference: whose purpose in life is more important?

AM: Humans have had this condition for such a long period of time, at least a couple of thousand years – as a state of mind, a state of being. I think it is also a reflection on the aspect of our lives that takes these things for granted.

RD: By striping the work of the source of violence are you afraid that the work may portray humans as being violent without cause? Are they separated, does the viewer have to find the context or apply their own context to it?

AM: I think the viewer is free to draw his own references or imagine his own context. I’m not making a qualitative judgement on the state of the human condition. For me at some point in time it becomes important to, purely as a personal engagement, make the work a reflection of how I was thinking, trying to express or understand that aspect of humanity. Although the body of work majorly constitutes this whole idea of war and violence, there are other aspects of human existence that I am interested in looking at which is why “the Other Bastardised Myths”. Originally it was going to be “Other Myths” but this whole idea of Bastardised became very interesting because the notion comes from how designers work as a collective and take a particular logo or a branding and bastardise it; coming up with newer, fresher, contemporary versions of it. That sense of innovation comes from bastardising a branding identity.

RD: It is a strange situation where you are taking something away from its [older] context but you also bring it back into history because it is a progression from the old to the new.

AM: It’s a way of relooking at an existing mythology; there is a certain hybridising of mythology or myth. Here by myth I mean there are certain constructs, they are codified constructs, that we call myths. They were originally constructed, and I’m using the word constructed in a very architecture specific context.

RD: Also, if you are looking at an archaeological site: the mound is constructed, it’s a set of various habitation periods [as strata]; it is very similar to knowledge that is passed on, one layer coming over the other. I think both of them [Architectural constructs and archaeological strata] can be viewed next to each other in this sense, for a more holistic explanation.

AM: Right, and I also feel that stories have that scope of evolving, folk tales have a large scope to evolve but myths are very rigid in their construction because they deal with these very universal ideological thought processes – the right vs. the wrong; the good vs. the evil. A lot of those ideas are constructed in a certain way so that you are meant to think in that fashion alone. It’s a type of feed/feedback that the human species has been generating as a constant. That’s what I think myths are supposed to be - constants.

Now, today in this whole trans-cultural, global environment that we live in myths have broken free of their individual, culture specific context. When east meets west you have something that is completely different, that hybrid space is what I’m interested in. That is the whole bastardising nature of our times.

RD: With the nature of your work, your interest in base narratives – that is where similarities may occur. If, as an example, we revisit the question of violence, it can be found in the myths of many cultures, in fact I would say all popular myths have violence in some form, whether perpetuated between enemies, friends, family, against a woman, or a woman or man against their children, between children and so on. So your work is at this basic nature, beyond cultural examples – it is beyond cultural.

AM: Yes, I decontextualised my work, at some point of time I began to strip the work of these cultural markers because I felt that that is where the whole universal quality of the nature of myth lies. In spite of that, myth has always been looked at very culture specifically; so how do we look at myth today, in this whole transcultural context? How do we look at it without that culture specificity that limits it?

The decontextualising of the images, the removal of the cultural markers, gives it a universal state of being. On the other hand the thin line that I have had to walk is how to not allow it to becoming something that will become very generic? In losing the specificity, the work could become so universal that it stops being relevant. So, the choices of the subject were dictated by the fact that I wanted to keep my work in this universal space; the very archetypal space. I think when I started looking at my work in that space, the whole notion of the archetype started entering my work as conscious attempts.

RD: When you play with the archetype, the completely striped human or animal nature, because some of your works involve animals, you give them human emotion – whether human and animal emotion is separate to begin with is a larger evolutionary debate – you impose your own identity on them through how you want to depict them or even in the figuration – what lines you choose to draw is your identity and it cannot be anyone else’s. Then this becomes an exception to your fear over something becoming so universal that it stops being relevant.

AM: Yeah, the whole style that developed over many years has created a very thin line between what I have said the work and the subject have demanded and what I have enjoyed doing. The composition, the scale, the structuring of the work has happened because the subject has been that larger than life mythic subject. This is how I work. On the other hand it’s not something that meant going against the grain for me. I very naturally enjoy working in this manner. I have felt that it is part of how things develop, very organically, very naturally. It’s not something that I debated about beyond a point in terms of the canvases. Then, of course, there was such a huge jump that happened because of the digital work.

RD: That is another question I wanted to ask you – you speak about this larger than life subject and beyond that the question of style, there is a compulsion to render it in a particular way. Even the necessity to create larger than life canvases in a metaphorical sense, did that require you to go the digital way? Of course this is besides your background in animation. Was there something that digital gave you that a traditional canvas did not?

AM: I’ve been doing digital work for a while on the side because that’s also something that I have very naturally gravitated towards and I have always maintained that the organic nature of oil is very unique and the digital work that I did earlier were in no way trying to compete with the oil. Specifically in this body of work, the Harlequin Series, my reasons for going into the digital state was more than technical. Although there is that aspect – yes I wanted that luminosity, I wanted an illuminated quality from the whole work. With the canvases there is a certain palette that we are used to, that there is a particular way to treat the works, so the digital work became a departure from a lot of that. There is a sense of play that came in specifically with that body of work which actually is intrinsic to the nature and the character of the harlequin.

RD: We have a point of comparison between digital and canvas when we compare the canvas with the harlequin and the hero that you had exhibited earlier with the digital harlequins that you have done. The starkness of the canvas does not restrict the feeling that you are trying to portray in the harlequin and in the hero, but the visual element is strikingly different between the two mediums. Maybe to an uninformed viewer (someone not familiar with the thought process behind it) the difference will be bigger. Are you afraid that the association might not happen easily?

AM: No, not really because in the journey that this full body of work now offers I think what you could look at is the drawing of the harlequin with the hero in comparison we could then also look at the title painting (The Ballad of the War that Never Was) which also has the harlequin and the hero amongst other characters; there is a certain difference between those two works and the digital works.

RD: In the title painting the starkness is not there, it’s almost like a transition between the drawing and the digital work.

AM: More than media I’m looking at three distinct spaces where the canvas, being a very organic, physical space in itself and the digital being this virtual and therefore non-physical, inorganic space and the drawings being somewhere in-between, a no man’s land. The harlequin in the canvas in The Ballad of the War that Never Was is almost like an outsider who is gazing at the group of people, by itself a very carnavalistic group. He is the only figure who is looking at the representative of the group as itself. In a work like Safdar where the hero has been rendered in a digital space, he is very out of his element. He’s being pulled in different directions because he is now in the harlequin’s state, his world, trapped. I think that that idea of space has also got to do a lot with not just a physical but also a mental space or a metaphysical space.

RD: I think you have implied in your notes that the hero in his organic world and the harlequin in a plastic world find it difficult to cross over. The trapping comes from the basic difference between organic and plastic.

AM: Exactly, I think that they are in mutually exclusive worlds, though they might sometimes find themselves in each other’s worlds but would then be the outsiders.

RD: Let’s now explore the harlequin and the hero and where they originate in your thought processes.

AM: The harlequin developed, as a character in my work, as an antithesis to the hero. The hero developed from an idea that he was a physical manifestation of the human spirit. For me the whole idea of the hero was that I wanted to talk about the human condition, the human spirit, and heroic acts. To my mind the human being of today is cast as a hero. We are in a liminal age where human beings are seeking haltingly, imperfectly to transform and transcend themselves. All around us we see acts of heroism and despair symbolic of this process. The human being today is cast as the hero of a myth. What happens if we strip the myths of cultural markings and reduced it to its essentials? I was looking at the hero as a representation of us, a very real representation of ourselves in this mythic scale.

Humanity has reached a crossroads and there is a dichotomy in everything that we are doing. There is a need to assert our identities; there is a need to re-evaluate old notions where we are coming from, whether it’s culture or a certain type of policy or an idea of a nation. Today, an already global, trans-cultural community, there is a certain deconstruction of ideas and ideology that we held to be true. In all of this there is a certain kind of dichotomy; a helplessness that I felt was the mood of the moment. That dichotomy that I was talking about was a physically very strong figure, but caught in moments of helplessness. It grew from that into a certain kind of a metaphysical or mental dichotomy as well.

RD: But then if we only had to look at the depiction there we could see that right there in the archetypal hero that you are trying to depict is a cultural marker that cannot be disassociated from it. If you compare say Indian and Greek mythology and the concept of the hero we find that in both cultures the hero’s destiny is affected by birth, at least the opportunity is affected by it. With Greek mythology heroes aren’t exclusively of high birth as the body too plays a big role in the acquisition of heroism; whereas in Indian mythology high birth is a very important factor in heroism.

AM: In the context of my work everybody is a hero, everybody is a hero of their own story, everybody goes through a certain similarity of processes that form the milestones and markers of any hero in either of the cultures. The context that I’m using the word hero is that there is in the structure of the story there is a character that undergoes a certain metamorphosis. This change or growth is the format of the story. The other characters may or may not have that growth pattern. There is a difference between the sutra and patra, the supporting cast and the hero. That process of being caught in that moment of change is why I’m using the word hero.

RD: Let’s then revisit violence. What can be said of the hero depicted in your work is that he does not rescue people from violence, he takes part in violence so that he can bear the brunt of its ill effects or we create that personality within us that takes the ill effects of the violence away from innocents or people that are not yet heroes or will not become heroes.

AM: Exactly, there is a certain quality of sacrifice that all heroes undergo; this moment-of-truth phase of sacrifice. In that sacrifice is the redemption.

RD: Then this is very far removed from the myth of Sisyphus. This is a real sacrifice.

AM: That (sacrifice and redemption) is actually the title of one of my works, The Identity of Violence Series: Sacrifice and Redemption , with the grey back ground and the red hands.

Ambiguity plays a very important part in my work. How the viewer defines the work for himself and how the viewer is contextualising the work forms in a very fundamental and intrinsic sense what the work would mean to that viewer.

RD: Are you afraid then that the names would lend meaning then to the viewer? You name each of them and assign a meaning and forgo complete abstraction and ambiguity.

AM: I think that titles are very important in my work because what I do with the titles is not to try to give a certain literal context to look at the work. Inherently the titles also have a capacity for multiple ways of looking at the work. What is an interesting exercise for me in terms of titling work is that the title takes you away from what you would have thought the meaning would have been. Sometimes it takes me away from the meaning, allowing me to not have a fixed meaning in my head. It gives a freedom to keep some openness.

My works are very layered and I like people to have multiple meanings. Sometimes people ask me: what is this work about? I always ask them first about what they think it is because I want them to have that dialogue with the work. Let the work speak to them directly rather than it coming through me because that is my interpretation.

RD: It’s then like a film name, where part of the meaning, or the theme is conveyed but not the whole.

AM: What I try to do and why the title of the work becomes so important is that they create a fundamental lens to view the works with but within that lens there is a lot of room for interpretation and a one on one dialogue with the work. The lensing is important because it creates a mood in which to look at the works. The whole idea of the hero may not even be the just the white figure but also the bull, the calf. There are very non-human elements, even the triptych, two panels are human and the third one is not. I very consciously try to not make it limiting in its nature.

RD: That’s an evolutionary debate: are the emotions that we have necessarily human? Do we share them with the greater animal world? The position that we put ourselves in, where we don’t want to associate our emotions with those that animals experience because of an assumed superiority clouds our judgement. Through your work, however, you want your viewer to equate a suffering animal with something that has sacrificed itself.

AM: The way I’m hoping the viewer will look at it is that here is a subject that is not obviously human in its physical construction or in terms of the use of figure actually but there is still a human emotion that is coming through. Emotion in that sense becomes very universal. What you said is true, maybe animals cannot be emoting the way we think that they are emoting.

RD: … or we have trained ourselves not to see it.

AM: But we have also trained ourselves to in the specific lensing of our own emotions.

RD: Let’s go back to the harlequin and look at what role he plays in our lives. Is he separated from humans, is he an implied human emotion or behaviour?

AM: As I said, the harlequin is the antithesis of the hero and his sense of helpless dichotomy in my works. Here is a character which is apparently in control of his environment, his world, he revels in chaos. He’s not concerned with right and wrong; he’s not concerned with fulfilling that implied, apparent destiny. He doesn’t get trapped in the dichotomy because I don’t think that he is concerned with that need to unravel things; in fact the chaos just adds to it. Among other things I think there is a whole range of a sense of play that has entered into this whole character because that is not there in the seriousness of the hero.

RD: While you were saying that I could not help but think that a lot of the music that you and me listen to have a lot of characters in it that are, in a sense, harlequins and even beyond the musicians themselves even the fans, like with Phish or the Grateful Dead take on this persona.

AM: Actually that reminds me, something that became a core reason for including the harlequin in my work was Fellini and his work I Clowns and his entire stated response to this genre, this carnavalist creature of the clown/jester. Fellini said that clowns terrify him and that he can’t imagine how people find them funny. That sense of how the clowns are this twisted macabre dark yet are covered in this very happy, clean slapstick humour but underneath that there is a very dark element of pathos as if they are these very twisted mirror images of society. Their also critics of society, that is very important function of any artist. I think when you are talking about the Grateful Dead or The Doors or Bob Dylan or when you talk of Marilyn Manson or a lot of subsequent artists you realise that they critiqued society apart from creating the next wave of culture. They were also somewhat removed from society. They looked at it [society] from a distance. I think the harlequin also does that.

RD: I guess that that is where human nature cannot differentiate between the harlequin and the hero in itself because, when you think about it, by becoming the harlequin these people have also taken on the role of the hero because they paved the way for broader mindsets in the future. As an example we may not appreciate the freedoms that comedians have today, that Lenny Bruce did not enjoy in his own time, where the consequences completely destroyed his life – he was a harlequin then but is a hero to today’s comedians.

AM: In fact there is a whole sense of tradition among with the whole community of the clowns and the fools. There is a certain kind of carrying forward of tradition, that is very important. I tried to take that element forward into my work, aligning myself to that tradition or at least a visual tradition of how the harlequin looks.

The harlequin finds its source in Dante’s Inferno and that is a very interesting starting point for a character. Dante introduces the harlequin or the hellequin in Inferno where they roam the streets with a band of devils searching for souls to drag back to hell, he is a minion of the Devil; a very dark character.

RD: That’s where society is today. A dark character does not need to be associated with devils or hell.

AM: We have removed the whole supernatural element of it; society has turned into this twisted version of itself. The Hellequin also became a symbol of life in the French passion plays. This was because of his many coloured hues; the range of emotions that he portrays. In contrast the hero is fixated on the singular nature of his existence. The harlequin has that range to play around with. There is a certain sense of menace and malaise that he exudes. For example in Safdar the harlequin becomes the society but in works like To Glory and Self he’s some kind of new monster. Here is a posture that is reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Adam but here is a character that is creating his world. His environment emanates from him and he is intrinsically tied to that environment, that chaos and that in turn creates him. Again talking of man as being the creator of its own existence, its own situation and how he himself is positioning himself further down the timeline.

RD: We should move on to how the base narratives of the hero and the harlequin come to us through one of your own influences, the comic book/graphic novel. Also let’s look at which characters in comics represent the hero and harlequin. If we were to name characters we have the Joker and the Riddler as very clear harlequin like characters however this cannot be said to be true for all villains. For example, in Superman, Lex Luther is far removed from the character of the harlequin and is almost a hero like villain with single, long term agenda.

AM: A very black and white situation would then be He-Man and Skeletor, which is also what Superman gets into. On the other hand with Batman and the Joker there is a different dynamic that is operative. The dynamic that they share comes from the whole Apollonian and Dionysian schools of thought, where Apollo is law and order and light and Dionysus is chaos but I would like to believe ordered chaos.

RD: He brings a balance that brings about order. So it is not an intended order.

AM: Right, something that is an order derived from that chaos because we probably do not have the capability to understand the patterns of chaos. So, those whole ideas of Dionysus and Apollo or even in Indian mythology of characters like Karna and Krishna. Where Karna is dictated by his perceived destiny and in that is his dilemma and his dichotomy and the helplessness but the character of Krishna who is free from that destiny because of his awareness of where he is comes from. It is very interesting that an avatar of Vishnu who is the preserver is Krishna who is the prankster, the trickster, brings chaos into the entire situation of the Mahabharata. This is not looking at them as characters that are actors but fundamental characteristics of human qualities.

RD: I think that is very important when you look at comic book characters, especially the ones which are being made into movie characters now. It is one thing to be a particular character, to have particular traits, where the madness or sacrifice or a desire for violence but it is also down to the person who plays the role. What kind of emotion is brought to the screen? This is more important than the dialogue, the spaces in comic books where there is no text and all that the character needs to tell the reader is rendered in figure and colour. Here, it is the actor drawing the comic book and in the movie the actor portrays the character as envisioned by the writer/artist. You are the actor playing the hero and the harlequin as well, in the sense of how you render them for the viewer, whether it’s coming from deep inside you or from a borrowed narrative.

AM: This would actually be a very good time to quote Joseph Campbell’s Masks of God, the opening of the chapter itself where he talks about the suspension of disbelief, that all forms of art must demand from its viewers, whether it is a ritual performance or painting or a theatre performance. Now we are talking about the fact that there is the mask created by the work and behind that I am the actor who is performing but it’s not me, it’s me who has become the character. At the end of the day it is these two distinct characters are becoming actors in themselves. What I wanted to point out through Campbell is that the fact that the mask has been worn makes the actor not an actor but for that particular time he is what he is portraying.

RD: But the actor lends himself to the public perception of the character for the future as well. In the instance of say a very memorable performance, where an actor steps in and becomes the character, using his own personality within the character, then every subsequent actor who performs the same role will be judged in the light of the memorable performance and may even portray the role imitating the performance rather than the writers intention. At this particular moment the actor is as important if not more important than the character.

AM: But what I am talking about is the whole context of the ritualistic performances, not even mythical subjects on television and in movies. The ritualistic performance actually transcends that and becomes mythic.

RD: Then we don’t have to go any further than Kerala where in Kathakali the actor is possessed by the character he portrays. I would still go as far as saying that even in this mysticism the actor still ends himself to the performance and that if comparisons were to be made over time, some would stand out over others. To put it in the context of the methodology, some actors may get more possessed than others.

AM: What interests me is this apparently simple word “becoming”. Whatever degree or capacity or capability that that person has become, the whole idea of that person becoming somebody or something else entirely; the idea of the becoming, the transformation, the transmutation; the fundamental nature of that word becoming has a distinct shift of something that is and something that is no longer. With the harlequin also, this is how I look at the character. You see how it seems to be a painted face and behind the painted face, the ears, the neck are natural. This is very consciously done because I didn’t want to create a face that was like that I wanted it to look as if there was something on a face. I’m interested in how he has become the harlequin; he is no longer a mere mortal. That isn’t his mask but his identity.

RD: Let’s talk about being at a particular place and the transition to where you are right now. When considering the fact that this is your first solo exhibition and you are putting all your work together, stuff that may or may not have been exhibited in group shows earlier marking a particular point in the journey of all your considerations into the human condition and this is what people are going to see. Without trying to create or impose a certain idea on people, what do you hope people understand about your work?

AM: I think what I would like the viewer to take back with them is the idea that over here is a work which doesn’t have a specific social context but it has a very specific human context. Here we are talking about something which is much more fundamental and deeper. It is very primal, the primary image, in relation to archetypes and how it affects us.

I want people to be affected emotionally at first, but they should question the work in relation to themselves and have that kind of a dialogue. Maybe be disturbed or unsettled but then try and find their answers to those turbulences, through this intrinsic idea of violence, of our existence in this particular time.

I want to take the viewers into this world that has been created; it is very different from the everyday reality of their existence. To look into the worlds, to see the images, to take the images into their depths.

RD: So you want the viewer to engage with a deep consideration of the world you have created by making sense of its inner working. You’ve drawn on mythology, particularly its modern version, would you want the audience to go back and consider this deep way of looking at the world which does not instantly strike you as real until you recognise it in its natural environment – our world?

AM: I don’t know if it is a deep thinking, I think that a lot of what is going on in the works now are things that I would attribute to everybody’s childhood. In my childhood, images and sounds and these ideas had a very primary and a greater than everything else significance.

RD: What I mean by deep is that our generation has taken it to imply any type of spiritual, holistic enquiry which would not necessarily be considered deep in the conventional sense though it might be.

AM: What I mean by childhood is a lot of these images that we are talking about, including existing archetypes and myths were created in the childhood of our existence. They have that very raw, emotive content, which we would associate with our own individual childhood – things like good and evil. Why do comics and mythic parallels start affecting us so much when we are children? Why do things like the enigmatic nature of people or the mysteries behind every day, simple, mundane, banal things seem so apparent when we were children because I think we tend to think very differently and it is that sense of childhood rawness that I want people to experience in a sense also?

Another series of works which is there is the whole photographic work where the stated intention is going into a childhood memory, where these characters, at least for me, had a certain kind of mystery, a certain kind of enigma like the golawala or a beggar who came in front of your car window or anyone else who occupies the street. They were there for a fleeting moment and then they would disappear. They became characters. I would always imagine, wonder about where they came from, what their lives must be like.

RD: So you implied the emotion that you feel or you imagine when you think about them through the perspective of the harlequin.

AM: As one grows up mysteries start dissipating, as we start to know things become less mysterious and what also inversely starts happening is that we start losing interest. We start to not see these people. I want to make them visible again and to infuse them with that sense of mystery and enigma. It is this revisiting that I am expecting, on a certain level, the viewer to have.

Comprehending Violence

Review by Abhishek Bandekar

It is amazing how you can know an artist as a friend for well over a decade, but still be surprised to learn aspects of his personality from his works. I’ve been proud to have Ali Akbar Mehta as a friend since 1999. My occasional annoying retreats into absence and isolation aside, his has been the voice that has spoken to me time and again from beyond the veneer of superficial film-informed notions of dosti.

To see, nay experience, Ali’s staggering and overwhelming collection of paintings in his first solo show was speaking to Ali in the non-diegetic. I’ve had these conversations with him, agreed non-emphatically over a society that has increasingly become desensitized to violence, both physical and emotional. And yet, witnessing on canvas all that has been spoken and that which has been unexpressed thanks to the finite nature of language, written or spoken; I was rendered speechless and in awe to respond clinically to what was a series of works that had hit me in the gut.

At Tao then, as I walked past the acrylic Sacrifice & Redemption from his Identity of Violence series to the digital prints on archival paper from his Harlequin series, I was challenged. The naïve critic in me questioned the lack of tangibility and the fabricated burden of the synthetic in the digital prints. But by the time I reached the Soliloquies in the Garden of Earthly Delights, it became amply evident to me that I had let my conditioning to govern my appreciation. The absence of ‘touch’ in the digital works precisely addresses the absence of the ‘enigmatic’ in our lives. In the post-apocalyptic world that Ali Akbar imagines, prophesizes, in his works, the digital prints on ‘archival’ paper offer a critique beyond just the content of those works.

Ali’s preoccupation is with ‘comprehending’ violence, more importantly violence as an entity that refuses to be transient but is instead embedded in our collective consciousness as an atavistic construct. This comes across most strikingly in his titular painting. But it perhaps is assertively addressed the most in what to me is the best work of this exhibition- The Great Mother Reconstruct(ed). Ali’s works have always dealt with man and beast, of the (d)evolutionary chasm between them and/or the lack of it. In Suppression & Rapture contrasted with Shwait, he explores this concept with remarkably effortless clarity. And yet, the absence of the ‘female’ in his works had always allowed room in his works to be ‘orphaned’. The Great Mother is one of Ali’s first works that introduces the trope of Eve in his paintings, and thereby adds promising dimensions to his already rich work. To have the image of Kali reimagined in a post-apocalyptic setting is to see the ‘creation’ of a myth. If the other works talk of a ‘detachment, of an existence after the seeking of the light (see the Ascension of Karna), the Great Mother is a direction back to the womb, of understanding all of Ali’s works and their concern from a damned cyclical perspective. This, and the graphite work War herald the next stage in Ali’s works. The promise of a brave new artist in a not so brave world!

Thank you Ali!

Nothing is Mundane

Interview by Jayeeta Mazumdar, for DNA India

Read here