Not on Noah’s Ark, but on the Raft of the Medusa

Essay by Ranjit Hoskote, Mumbai, 2011

Normality is the somewhat misleading name that many of us give to the present. It is often the only means of remaining sane while enduring the abrupt horrors and dehumanising provocations that surround us. The artist, however, is not obliged either to neutralise himself to these horrors and provocations; nor is he afraid of exploring the regimes of consciousness that lie beneath the sanctioned threshold of sanity.

And so the jesters, harlequins, cerecloth-swaddled zombies and explosion- flayed refugees who populate Ali Akbar Mehta’s paintings and digital works are not strangers. Not at all, for we know them intimately well, these figures who dominate the 1983-born Mehta’s first solo exhibition: they are ourselves an hour from now, a decade from now, in the near future, or at any moment. Allegories of the present, veiled thinly as a post apocalyptic future, Mehta’s works alternate, tonally, between melancholia and the ludic, between Lent and Carnival. They emerge from a long tradition of critique-through-image that turns our conventions of time, space, gravity and propriety topsy-turvy: a tradition that counts, among its major exponents, Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Brueghel.

On the testimony of these works, produced between 2006 and 2011, Mehta is an explorer charting a demon-haunted world that balances precariously between compassion and oppression, instability and militarisation; the mushroom cloud of nuclear annihilation is always billowing on its horizon.

*

Mehta is a member of what has been called the generation of ‘digital natives’, who grew up with personal computers, wireless telephony, and electronic retrieval systems of every size and scale. The translation of substance into immaterial form is a basic parameter of the lifeworld he inhabits; with it comes the understanding that data flows rather than being confined, and that images and episodes too are part of ongoing, vast narratives rather than remaining in guarded pools.

Having been exposed to animation as a creative form in his parents’ animation studio, Mehta also embraces comic books, graphic novels, manga and anime as cultural resources.

Ali Akbar Mehta_Harlequin Series; To Glory in Self, like some kind of New Monster, 2010, Archival print on Hahnemuhle paper, 182 x 121 cm

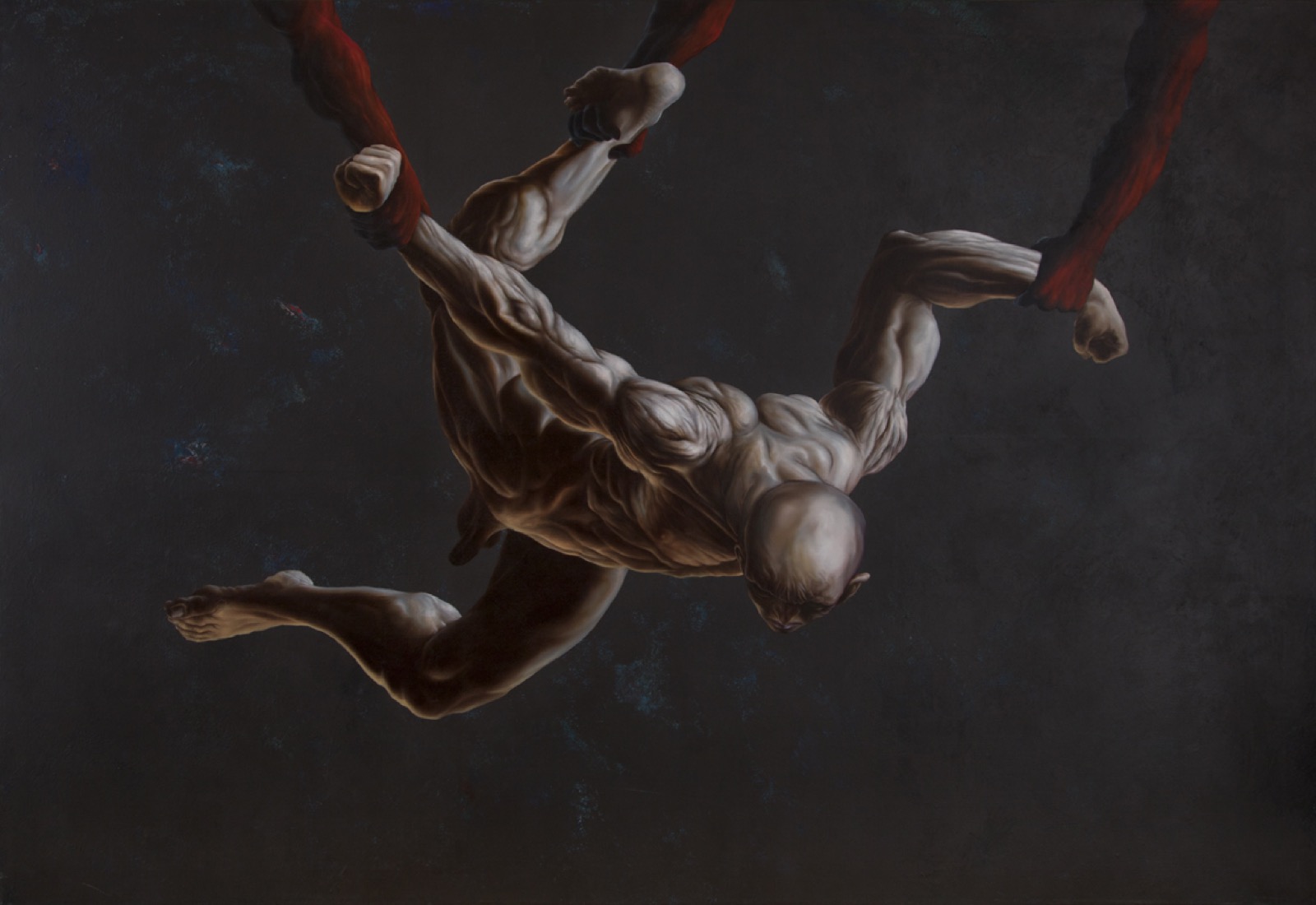

Naturally, then, Mehta is fascinated by the figure of the superhero: who is supremely powerful yet deeply vulnerable, benevolent yet sinister, weighed down by the knowledge of humankind’s ultimate fate yet aware of his role as a guardian of hope and renewal. If the archetype of the great hero enshrines the spirit of indomitable resilience, it also incarnates all the freight of fear and paralysing anguish to which humankind is heir. In many of Mehta’s figures, the ligaments are stretched, the bone is set at breaking point. Indeed, in Mehta’s handing, the body is often an unsettling hybrid of muscular presence and spectral apparition: it is made, seemingly, of ectoplasm or pulp that has momentarily assumed a shape which it may lose without notice.

In Mehta’s imagery of the suffering yet defiant body, we may detect an act of homage to his grandfather, the legendary artist Tyeb Mehta. We find this especially in the trussed figure, suspended from ropes, more prisoner than marionette and hung above the abyss, in ‘The Identity of Violence Series: Suffering and Rapture’(2010). That homage also animates the figure that has been twisted, knotted, folded double in ‘Triptych’ (2007) and jammed into the cage formed by the frame of the canvas.

Ali Akbar Mehta_The Identity of Violence Series; Sacrifice and Redemption, 2010, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 182 x 121 cm

*

Mehta’s preparatory process involves a theatre-like ‘characterisation’ of his protagonists: a detailed imagining of their ‘inner lives’, a fleshing-out of their ‘back stories’, a calibration of their emotional temperature based on episodes deemed to have taken place in the past of their fictive present scenarios. As in theatre, this characterisation is not made wholly explicit in the articulated form of the work; nor is it meant to be. Rather, it serves the artist as the substance that confers reality upon his characters, and is the continuing material substrate from which his images and the narratives that concern them will be conjured.

Mehta delights in portraying quixotic figures of unpredictable motivation as they move through the columned halls and terraces of normality, replacing these with the weaving shapes of hallucination and phantasmagoria.

*

Among his protagonists are the jester and the harlequin: the first permitted to speak truth to power, although in politically sanctioned satire and allegory; the second a shape-shifting trickster who celebrates all that is chaotic and out of joint. Accordingly, the artist favours a pictorial space that is psychedelic, its emphasis laid on the play of strange lights and pulsating auras. Indeed, to this observer, his canvases articulate the ominous psychological freight of Bikash Bhattacharya’s paintings of the 1970s.

Humankind lurches from one crisis to the next in Mehta’s post-apocalyptic ecologies, with little chance of redemption. We find predators and victims, survivors and demons, all conjoined in a common destiny, all adrift: not on a Noachic Ark so much as on a Gericauldian Raft of the Medusa. In the painting that gives this exhibition its title, ‘The Ballad of The War That Never Was’ (2010), one of the key figures is modelled on the Deposition, the enduring moment when the crucified Christ is taken down from the cross, except that this figure has no hope of resurrection; another figure in this tableau is based on Delacroix’s ‘Liberty Leading the People’, except that the banner is fraying, torn to pieces by the wind.

Ballad of The War That Never Was, 2011, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 152 x 198 cm

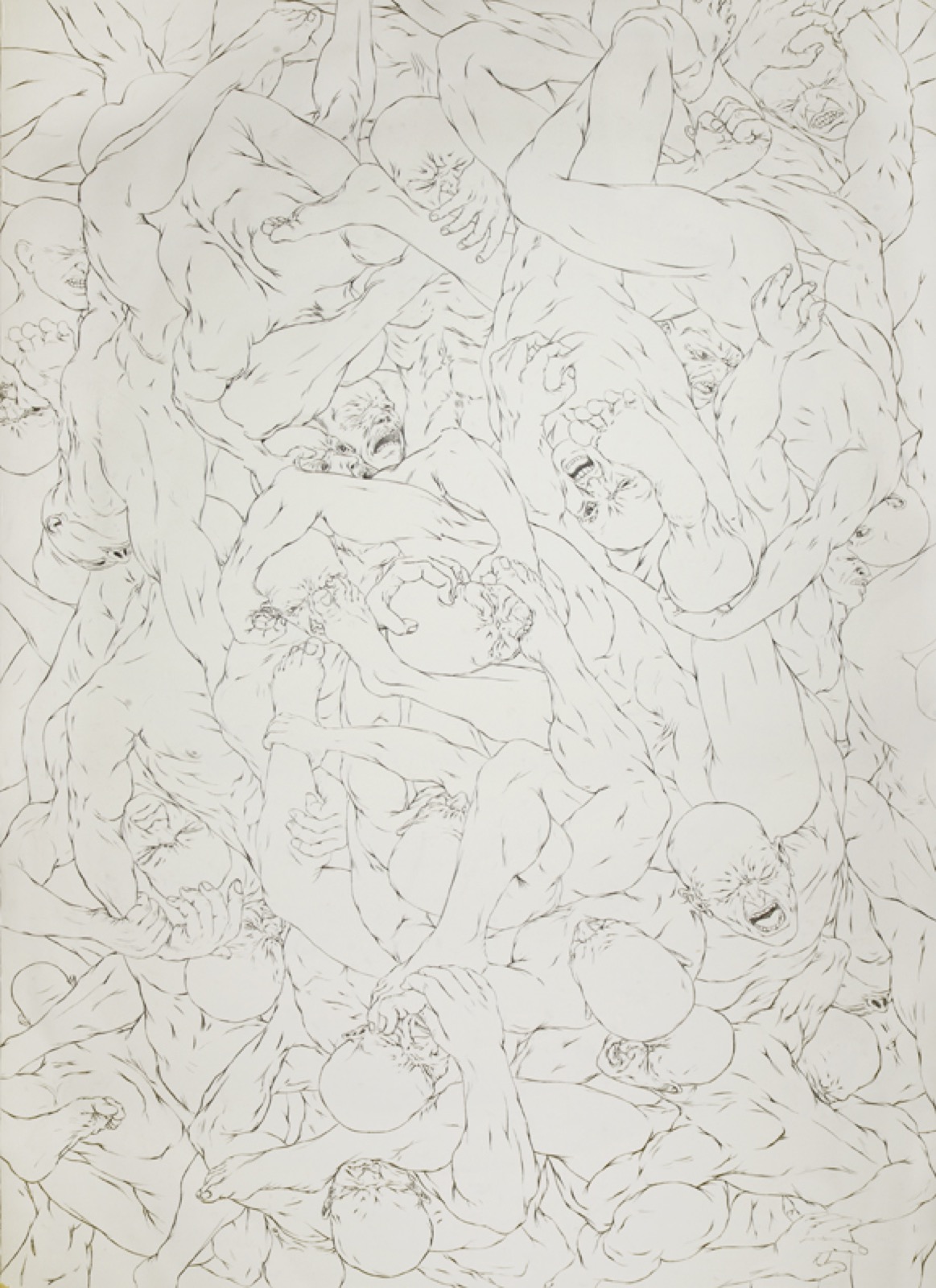

Or, as with the close-packed figures in ‘War’ (2011), screaming as they flail, wrestle and fall together in a grand tapestry of the damned, Mehta’s figures strike us as a contemporary version of Dante’s eternally condemned figures in the Inferno or Michelangelo’s in the Sistine ‘Last Judgement’. The mode of the history painting manifests itself again and again in Mehta’s work, through allusion and citation. But the inspired certitudes of history painting and its heroic belief in the ability of the human will to dominate all circumstance have yielded, in Mehta’s paintings, before a more tragic awareness of human fragility. This artist does indeed take man as the measure of all things, in the classical humanist formulation; but man is here a strained measure, bent under pressure. Precisely for this reason, Mehta’s protagonists speak to us of our own anxieties and exhilarations, sing to us of our own at-once epic and intimate predicaments.

Ranjit Hoskote

Mumbai, 2011