Atlas of Lost Beliefs (for Insurgents, Citizens, & Untitled Bodies)

Curatorial text by Ali Akbar Mehta, Museum of Impossible Forms, Helsinki

The Atlas is ‘a book of maps or charts’. We gazed into the Atlas and dreamt of places we would like to visit. The Atlas was our window to strange and alien worlds, connected by an incomprehensible amount of water. Today, the Atlas as a portal, as a device for dreaming is a forgotten artefact, instead mired in historiographies and anthro-political readings of a world that was. Even now in a time obsessed with the past, devoted as it is to the cult of memory and the fetish of heritage, something still goes forward. Even now when there is no general direction, nor a subject who is supposed to lead, we cannot but ask where to place our next step, what to take along or leave behind. Yet there are still prospects, or in philosopher Bruno Latour’s words, “the shape of things to come.”

This future-forward projection of culture is enacted, in part, by Museum of Impossible Forms, because that is what we choose to do. Choice here is active participation.

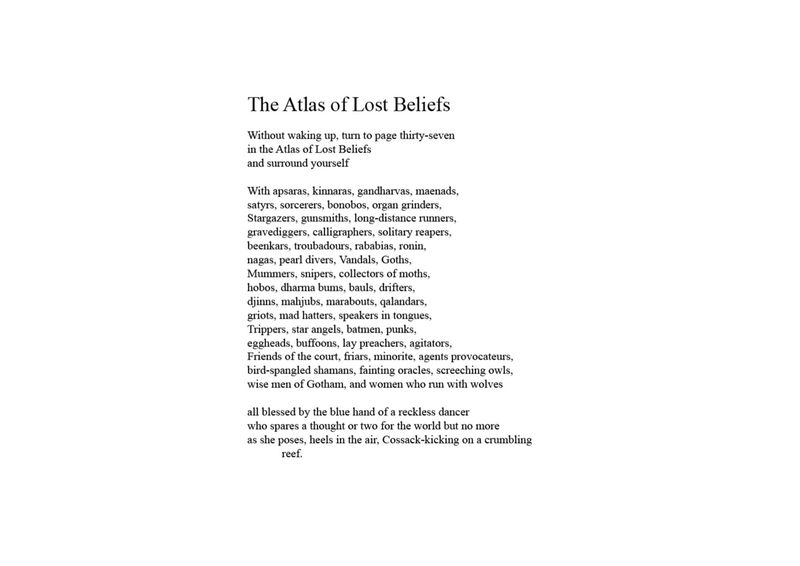

In the poem, Atlas of Lost Beliefs, Ranjit Hoskote evokes an excerpt, a glimpse of a possible host of personas, both real and fictional, whom I can’t help but read as being ‘fellow insurgents, citizens, and untitled bodies’, all trying to swim in contaminated circumstances, to stay afloat in the infinite waters of precarity, seeking footing despite their groundlessness, subaltern characters not so very different from all of us – we are or have been each of them at some point in time, often all three, simultaneously, silently. And so we dedicate the coming year in solidarity with these, the cast of our collective narratives that connect the waters of our Atlas, who frame and address the engagement of cultural production with political and cultural predicaments in locations not ‘their own’ – whether described from a narrowly territorial point of view or within the contexts of secular, transnational, democratic, decolonial, queer, norm critical world(s); who allow us to ask, ‘What comes next?’

What can we learn from the Museum beyond what it shows us?

The real issue concerning museum building as a possible form of critical praxis, are ways in which praxis can contribute to questioning the dominant hegemony. Once we accept that identities are never pre-given but that they are always the result of processes of identification, that they are discursively constructed, the question that arises is the type of identity that critical artistic practices should aim at fostering.

Peter Mayo, who writes on both Gramsci and Freire, asks a simple question that all political (meaning all) education must ask itself: “what side are we on when [we] teach, educate and act?” The ‘postmodern condition’ has now cornered us in a seemingly impossible situation –we are compelled to seek alternate histories in order to achieve an impossible balance between knowledge and the power it produces.

The Museum will lead us in directions of knowledges we didn’t know we needed to ask.

We at Museum of Impossible Forms wish to complicate the words ‘Museum’, and ‘Impossible’. For us, the word museum already contains within it the contemporary notions of the para-museum, the counter museum, the anti-museum. The ‘Museum’ no longer represents the ivory towers and petrification machines, where objects are preserved and inventoried in accordance with their cultural and historical ‘value’. Rather, they must take upon themselves to (re) establish their relationship to society and take on the role of being educational.

Museums today must ask on a regular basis, what must be done? Not just for itself, but for us, as members of a socio-political society. It must ask, how do we choose to act? How do we choose to act – In our media saturated, Socially omnipresent, politically fractured, economically segregated, Xenophobic, Disembodied world?

Museum of Impossible Forms is a partial response towards the engulfment of a responsibility to facilitate and/or empower the facilitation of a new kind of para-institution, as a space for learning, unlearning and relearning; as a space to listen and be heard; and as a space that constitutes our own, collective yet personal ‘Atlas’.

[1] Ranjit Hoskote, ‘Jonahwhale’, Penguin Random House India, 2018, p. 7

Read more texts on the Museum of Impossible Forms website here